Sanskrit is the language of divinity: V-P Dhankhar

Prior to the convocation ceremony, the Vice-President had darshan at the holy Tirumala temple.

The only use of Sanskrit I saw was on religious occasions. The Hindu rituals are all conducted in Sanskrit as opposed to the common language spoken by the local followers.

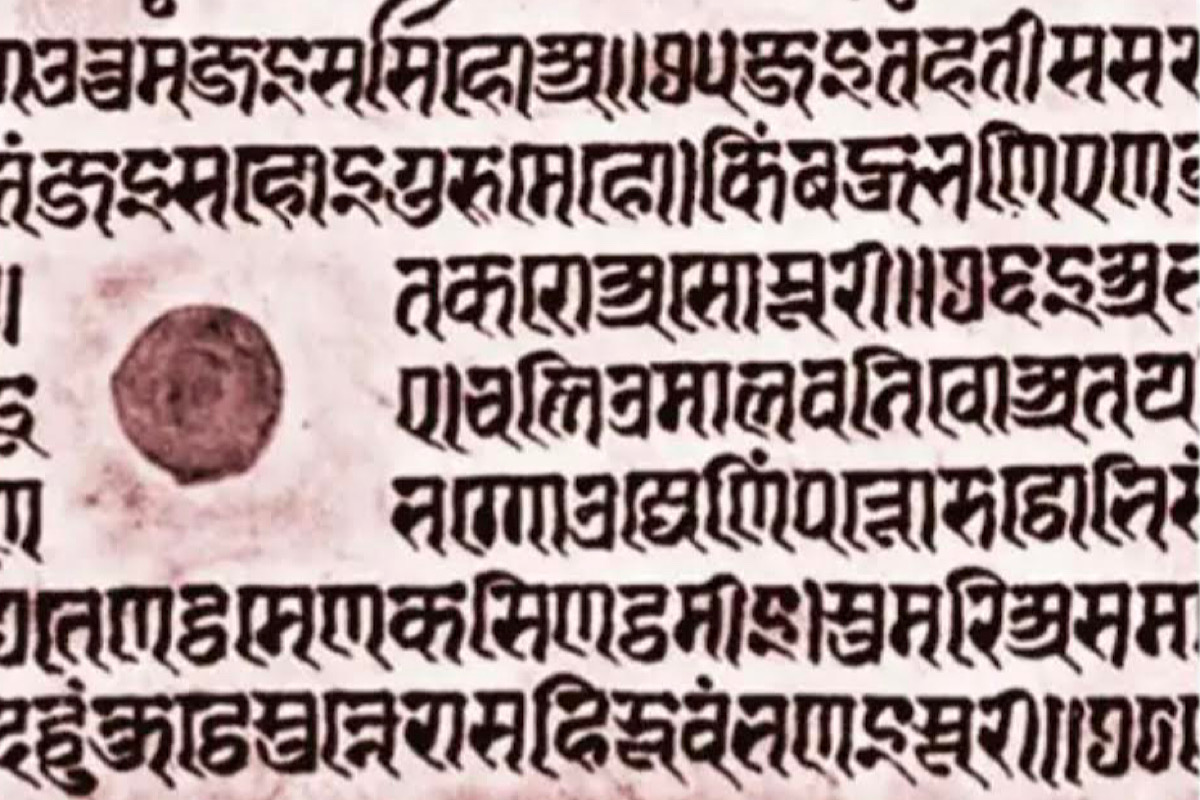

Representation Image [PHOTO:SNS]

Language day is celebrated in Bangladesh every year on February 21 in memory of all the martyrs who sacrificed their lives defending their mother tongue, Bengali from the Urdu-speaking Pakistani government. The United Nations later designated this day as the International Mother Language Day, to be celebrated across the globe. At this time, I wonder if we should fight for linguistic survival of Sanskrit – not our mother tongue but perhaps of equal significance in Indian history.

Sanskrit was my third language (after Bengali and English) in middle school. I chose Sanskrit at the urging of my mother. My other choice was French since my school was in Chandannagar, a former French colony, about 25 miles from Kolkata. I was happy with my choice. I knew that Sanskrit was the origin of most Indian languages. There was an endless supply of difficult but beautiful words formed using Sanskrit grammar. My grades were good. I could even recite entire essays in Sanskrit.

Later in life, I realized that French might have been a better choice because I worked for a French company for a few years and visited France numerous times.

Advertisement

The only use of Sanskrit I saw was on religious occasions. The Hindu rituals are all conducted in Sanskrit as opposed to the common language spoken by the local followers. This is true in all pujas, wedding ceremonies, annaprasans (rice ceremonies), shraddhas and so on. Modern versions and not the original versions of ancient languages like Arabic and Hebrew are used on Islamic and Jewish religious occasions. Unfortunately, Sanskrit is a “dead” language with no modern version.

However, Sanskrit gives the occasion a sombre and divine flavour, commanding respect, ardour and silence.

Unfortunately, there are undesirable ramifications of this practice. Most people participating in the occasion do not have any clue about what the “purohit” (priest) is saying. They just silently sit there and listen even when the ceremony goes on for hours because they want to appear to be pious and religious followers.

Secondly, the practice of conducting the step-by-step religious procedure has been restricted to Brahmin “purohits” presumably because of their ability to understand and recite scriptures written in Sanskrit. We give them complete freedom in deciding how they do their business. Some suspect that it was the Brahmins who protected their profession by insisting on keeping the tradition of using Sanskrit as a religious language and restricting the practice to Brahmins.

The difficult Sanskrit slokas from the scriptures are a deterrent to the younger generation to reading religious books and/or becoming interested in pursuing a path in theology or similar disciplines. I can confess that I have never read the Gita or Upanishad or Vedanta, precisely because I thought that it would be difficult reading. Even the simpler versions, written in Bengali or English, seem to dwell on lengthy interpretations of Sanskrit slokas as opposed to paraphrasing the contents in a simpler language.

Rediscovery of my spiritual roots came from reading “An Autobiography of a Yogi” by Paramhansa Yogananda and Chapter 43 in particular. It is written in plain English (also available in many other languages) with occasional humour. Yogananda did not use Sanskrit slokas or difficult language and it was enjoyable reading.

I wish that there were similar books available for our young people written in Bengali, Hindi or English explaining the key concepts and philosophies in our scriptures.

Despite modernization and liberalization in our outlook, when it comes to organizing, say a wedding for our children, we automatically look for a Brahmin purohit to administer the ceremony in Sanskrit, even though the Indian Supreme Court ruled in 2015 that Hindu religious ceremonies could be conducted by non-Brahmins.

The “mantras”, “vows”, “anjalis” etc. can be easily translated into Bengali, Hindi or even English so that everyone can understand and appreciate their significance. Many pleasant devotional songs addressed to Hindu Goddesses, available in both Hindi and English on YouTube.com channel, might substitute for long recitals in Sanskrit.

Many people believe that Sanskrit is a useless language, and its use should be phased out from not only our religious celebrations but also studies in school.

However, such a move is neither easy nor wise. There is a revival of the language going on in India. One school of thought strongly believes that many concepts and messages in our scriptures would be distorted if translated into any language other than Sanskrit.

There have also been movements to make Sanskrit our one and only national official language for the sake of unification of the country. Although Hindi is our official language, there is a strong anti-Hindi sentiment in the southern part of India. However, languages such as Tamil are reportedly much closer to Sanskrit. Sanskrit is believed to be “Deva Vani” or the language of Gods without any provincial association which makes it ideal for a national language. In any case, we can make it a compulsory language at all schools throughout the country.

There is a central organization, Samskrita Bharati to promote these activities. Uttarakhand became the first state in India to adopt Sanskrit as a second official language in 2010 and Himachal Pradesh did the same thing in 2018. Awards were given by the Indian Council of Cultural Research for studies in Sanskrit. This revival is taking place not only in India but also in other countries. Sanskrit is offered as a college course in numerous universities and other institutes throughout the world.

Many political leaders strongly advocate a “rebirth” of Sanskrit because ancient Hindu literature on science, mathematics, and medicine, all written in Sanskrit were the pioneering sources of knowledge in their respective fields. It is also supposedly the perfect language for artificial intelligence because it is easier to program the grammar of Sanskrit language.

Even without these political and government activities, we are already immersed in Sanskrit perhaps without even realizing it. Many Indian names have their origins in Sanskrit. Many of our mottos in various organizations are in Sanskrit, the most famous one being, “Satyameva Jayate”.

Our national anthem is in Sanskrit as well as the song “Vande Mataram”. We often use cliches which are in Sanskrit such as “Satyam, Shivam, Sundaram”.

Sanskrit has also influenced languages in other countries in Asia and been incorporated in scriptures of multiple religions including Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism and Sikhism. Even many words in English such as “path”, “door”, “man”, “attack”, “serpent” are derived from corresponding Sanskrit words “patha”, “dwar”, “manu”, “akramana” and “sarpa”.

Is there a middle ground where we can reach a compromise between wide-spread use or elimination of Sanskrit? A good solution could be the introduction of a modern version of Sanskrit which has easier grammar and fewer difficult words. It can certainly be made a mandatory second or third language at school. There should be non-religious books written in Sanskrit. Online English or Hindi to Sanskrit dictionaries are already available to facilitate this practice.

To make Sanskrit appealing to the younger generation, infusion of Sanskrit words in the lyrics of songs could be a good approach. In fact, rappers like Raja Kumari and Shlovij (aka Shagun Sharma) have already incorporated such words in their songs.

In addition to promoting literature and music in Sanskrit, perhaps movies can be made in Sanskrit. Mel Gibson has shown the way in this regard. Dialogues in his movies “Passion of the Christ” and “Apocalypto” were entirely in Latin/Hebrew and Mayan language respectively, with English subtitles.

The Sanskrit language is our national treasure. We do not have to make it part and parcel of our daily life in this twenty-first century, but we can certainly make room for it in our intellectual, scholarly and recreational activities.

(The writer, a physicist who worked in academia and industry, is a Bengali settled in the United States.)

Advertisement