Cong defeated ‘Bangladesh’ in semis, will rout ‘Pakistan’ in finals: Reddy

Reddy was addressing a meeting of the Congress social media team and took digs at both the BJP and the BRS.

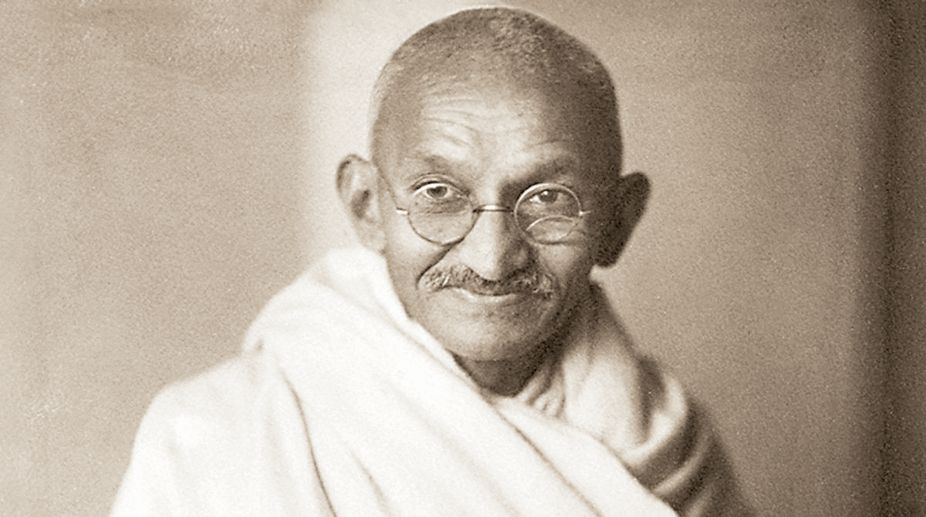

M.K Gandhi (Photo: SNS)

As I was struggling to make time for this article for the past few days – and failing – my frustration was especially keen. Not simply because the occasion was the 70th death anniversary of M.K Gandhi, who is still the most prominent icon of India and its democracy, but I was dying also to give vent to a sense of rueful irony inherent in the fact that the Mahatma’s last and seventeenth fast was undertaken for the sake of communal amity, so that two newly born nations of India and Pakistan could be saved from religiously motivated mayhem.

Now that the Indian nation is witnessing a new surge of religious fundamentalism – now that nationalism is defined in terms of loyalty to the dogma of Hindu superiority, now that the murder of innocent ordinary Muslims and liberal Hindus by ultra-right outfits have become routine – how ironic seems that last, agonising fast by the aged Father of the Nation. How ironic and how sadly futile, indeed!

At the stroke of midnight on 15 August 1947 India, as we know, did not awake only to freedom and definitely not to light. It awoke instead to the darkness of intense communal hostilities, the darkness that was visible through the length and breadth of the country, and especially in Calcutta, Delhi and Punjab. Trains full of expelled Hindus and Sikhs arriving in India from Pakistan were being torched by Muslims, just as those containing Muslims were being torched by Hindus and Sikhs. Both nations were burning. Peace seemed a distant dream, scores of women on either side were raped, entire neighbourhoods were gutted, thousands of lives were lost and many more were endangered.

Advertisement

It was in these circumstances that Gandhi – by then informally anointed as the Father of the nation – started his seventeenth fast unto death, the fast that turned out to be his last. It was in September 1947. The Mahatma was in erstwhile Calcutta, gripped by communal strife. The frail old man, pushing 79, saved the city from horrific ruin. After several days of his fast the warring groups – the Hindu Mahasabha on one side and the Muslim League on the other – jointly promised Gandhi that they would stop fighting.

By 9 September Bapu was in Delhi. The city, he saw, was in the grip of rabid Hindus who were persecuting, looting, killing the city’s Muslims. Gandhi was alive to the fact that Pakistan was being barbaric to its Hindu-Sikh minorities, but was confident that if Delhi stopped retaliatory violence the persecution of Hindus and Sikhs in Pakistan would cease as well.

In a desperate attempt to reach to the root of the tensions Gandhi appealed to Golwalker, the leader of the Rashtriya Sayamsevak Sangh which he reckoned was the chief power loci of the Hindu extremists. While paying lip service to Hindu-Muslim harmony, Golwalker did not agree to announce before the public that the Sangh did not endorse Muslim persecution. Now, when ideological descendants of the likes of Golwalker and Savarker are determined to spread a Hindu supremacist, divisive ‘nationalism’ in the country, Gandhi’s vision of a peacefully pluralistic India increasingly recedes into history, making a travesty of his life’s work, and proving us to be undeserving of his great legacy.

To come back to the narrative, even as Delhi continued to be in flames, Gandhi’s fast continued. By the middle of January 1948, his health started failing badly. Nehru, Patel and other leaders of the Congress went all out to convince him to break his fast. However, the public mood was different. G.D Birla’s house in Delhi, where the fasting Gandhi was sheltered, was mobbed by Hindus and the Sikhs who by now perceived Gandhi to be positively pro-Pakistan. While dealing with them firmly, Nehru, nonetheless, made an impassioned appeal to all communities to save Bapu. Gandhi’s death amidst communal discord, he declared, would be the death of the soul of the nation and Independence would be meaningless.

Meanwhile, Gandhi effectively started to die. Deeply distressed, Nehru, Patel, Rajendra Prasad and others decided to pay Pakistan the sum of Rs 55 crore that India owed as per an agreement to divide the assets of pre-Independence India, something that Gandhi had been asking them to do. Still, Gandhi’s barely audible voice made it clear that only true brotherhood among all communities of Delhi could make him relent.

On 17 January 1948, even as the Mahatma lay dying, the leaders of the nation convened an all-party Peace Committee meeting at which they formally pledged to work towards generating the spirit of peace and fraternity among the different communities of India. Still, Gandhi was not convinced. Understandably, for the ‘all-party’ agreement lacked the signatures of the leaders of the Hindu Mahasabha and the RSS. It needed another round of talks and further deterioration of Gandhi’s health to convince Ganesh Dutta, the representative of these outfits, to commit to communal amity. On 18 January, he promised the dying Father of the Nation that they would help rehabilitate the expelled Muslims of Delhi, if they chose to come back. The victorious Gandhi broke his fast and came back from the brink of death. Now, it was planned, he would go to Pakistan in order to convince the government of the new nation to commit to the welfare and security of its minorities and its downtrodden. After all, he was the Father not only of India, but also of its sibling Pakistan.

This trip, as we know, did not happen. Even as the aged Gandhi staked his life for the sake of communal harmony certain sections of his own community remained unmoved. All of Bapu’s love and wisdom could not soften their stony-hearted, fanatical hatred of Muslims. In the Mahatma they saw not a messiah of love and peace but a deadly enemy of Hinduism. One of these Hindu fanatics from Pune, the notorious Nathuram Godse, shot him from close range on 30 January 1948. Gandhi, a devout Hindu himself, died with the name of his God on his lips.

Even as I write this, seventy years after that murder shocked and benumbed our fledgling nation, my heart fills not only grief but also with a galling cynicism. If the Mahatma’s uttermost commitment to Truth and Peace, and his self-effacing lifelong work among the people could not root out the canker of religious fanaticism and hatred, what will? Until recently, the world used to respect us for our great tradition of religio-cultural pluralism, for being the strongest democracy in Asia and, above all, for being descendants of the Mahatma, whose brilliant crusade for liberty and peace inspired the likes of Martin Luther King and Nelson Mandela.

But today, increasingly, we are losing that position of respect in the world. Our chief point of pride – our pluralistic democracy and our secularism – are under deep threat. We too are going the way of the rest of the world – on the path of fundamentalism and the resultant culture of hatred, violence and solipsism. We are moving our face away from the light of Reason to the darkness of religious extremism. We are putting to waste the life’s work of the Father of our nation. Cry the beloved country!

The writer is Assistant Professor of English, Krishnath College, Berhampore, West Bengal.

Advertisement