History tells us that women in different parts of the world have been fighting against political persecution, social deprivation and gender discrimination. The Nobel Peace Prize memorialises their achievements and courage and ability to inspire hope in others. Through the life portraits of 16 women Nobel Peace laureates, peace activist and journalist Supriya Vani argues that the fate of the world is inextricably tied to the emancipation of women, and that the cause of world peace urgently requires women leaders.

After a brief foreword by Kailash Satyarthi, Vani tells us that she scripted the sagas of 16 women, who in their meeting with humanity found self-fulfilment through their unbound love and relentless struggle for peace and justice. Going from more recent times to that of the past, she begins her book with the case of Malala Yousafzai, who became internationally famous at the tender age of 14 as a child campaigner for girls’ education in the Swat Valley of Pakistan.

The story of the nearfatal attack by the Taliban in 2002 only afforded Malala an audience which was larger and her sacrifice immediately captured the imagination of people across the globe. Inheriting her father Ziauddin’s fearlessness, Malala’s courage and determination is prodigious, as her passion for the emancipation of repressed women around the world is manifest. The next remarkable woman is Ellen Johnson Sirleaf from Liberia who became Africa’s first Woman Head of State in 2005. Just as innumerable women have done before, and almost as many since, Ellen endured her abusive marriage far beyond the dictates of reason.

During the trauma of civil and mindless violence she confronted the situation with her inner reserves and utmost fortitude. In spite of facing elimination and being hounded wherever she went, she became almost like a folk hero as she placed her concern for her country and its people above not just her personal comfort, but her safety. She has elevated womanhood in the African continent to its true place of honour and dignity.

Another recipient of the prize from Liberia in 2011 is Leymah Gbowee. As a common woman, she was able to overcome adversity to become an iconic figure for her nation and a paragon of women’s empowerment for the world. And all the while she nurtured her family and rebuilt her self-worth from the ruins of an abusive relationship. It is really inspiring to read about her transformation from a povertystricken and half-starved mother to an enlightened peace activist. She had allowed herself to be sexually exploited and had become trapped in a dysfunctional relationship for the security of her children and through her work in redeeming the lives of others, Leymah had found her own redemption.

Sharing the honour of the Nobel Peace Prize in 2011 along with Ellen Johnson Sirleaf and Leymah Gbowee, was Tawakkol Karman, the Yemeni journalist, human rights activist, politician and senior member of the Al-Islah political party. She was the second Muslim woman after Shirin Ebadi of Iran to have received the prize for being “a courageous lady who has never heeded threats to her own safety.” Her declaration, “I am a universal citizen. The earth is my homeland and humanity is my nation,” gives voice to an ethos that is the very essence of peace. She has garnered respect for her advocacy of women’s rights in a country not at all noted for feminism.

As a wife, mother and practising Muslim, who removed her niqab and started wearing a colourful hijab, she is also among the most prominent activists in the Arab world. The next honour goes to Wangari Maathai of Kenya. Being the first East African woman to receive a doctorate, and subsequently dismissed from her university job on flimsy grounds, Wangari got deeply involved in the Green Belt Movement, which protested against land-grabbing by the government.

Receiving the Nobel Peace Prize for 2004, it is important to keep in mind, while judging Wangari’s work, that her political machinations were intended not just to further immediate political goals but also to make way for larger, more extensive social changes, especially regarding climate change, sustainable development and a cultural renewal of the Kenyan people who had long reeled under the colonial yoke. Shirin Ebadi, Iranian lawyer, human rights activist, former judge and founding member of Defenders of Human Rights Center in Iran, was the recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize for 2002.

She is the only Iranian and the first Muslim woman to receive the award because of her ability to confront injustice and tyranny in her country. Along with her female compatriots, she had to come to terms with living under the tyranny of the Komiteh, the morality police. According to the Islamic Penal Code, a woman’s worth is equal to half that of a man.

Shirin had successfully mobilised support to change blatantly unjust laws which favoured men’s primacy over common sense and children’s welfare. She continued fighting for justice for those killed for espousing freedom of expression. Jody Williams became the 10th woman and third American woman recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize in 1997. Her work also involved overseeing an endeavour to heal the broken bodies of children caught in the vicious guerrilla fighting between the government and rebel forces in Central America, especially in El Salvador.

Her efforts culminated in an international treaty banning anti-personnel mines and her campaigning against landmines can be viewed as something of a great spiritual quest, and she conducted it with religious fervour. Over the years, Rigoberta Menchu Tum has emerged as the chief leader and advocate of American Indian rights and ethno-cultural reconciliation both in Guatemala and in the Western hemisphere.

As a crusader for indigenous rights of the people of Guatemala, even at the expense of facing mounting threats to her life, she won the battle against the military establishment in her country. She received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1992 and eventually expanded her activities across the globe. On 14 October 1991, the Norwegian Nobel Committee announced that Aung San Suu Kyi would be conferred that year’s Nobel Peace Prize “for her non-violent struggle for democracy and human rights in Myanmar”.

Ironically, it was only on 16 June 2012 that she could finally deliver her Nobel Lecture at Oslo City Hall, more than two decades after being awarded the prize. A long-term house-arrest and oppression by the ruling junta could not veer her from the path of non-violence. Sacrificing her personal family life for the betterment of her country, Suu Kyi was drawn inexorably into the intrigues, factionalism, treachery and outright danger of Burmese politics eventually being able to succeed in her mission.

Alva Myrdal, Swedish sociologist, diplomat, politician and staunch proponent of nuclear disarmament is often spoken of along with her illustrious husband, Gunnar Myrdal, but her personal contributions cannot be overestimated. She received the prize in 1982. Mother Teresa’s life and work is so well known that it needs no elaboration. Hailed by the world as the “Saint of the Gutters”, she has enhanced the prestige of the Nobel Peace Prize. In 1976 Betty Williams was awarded the Peace Prize along with Mairead Maguire from Ireland, who constantly strives for a non-violent world. As a Christian, Mairead assumes responsibility for all wrongs committed by Christians. From sympathising with the IRA, Williams also went on to fully denounce violence and become convinced of the virtues of pacifism.

In history, it is rare for a woman to have waged a crusade opposing one’s own country and braving public condemnation as did Jane Addams. She was part of the vanguard of peace activists who successfully campaigned to stop the US from entering World War I. She became the second woman and the first American to receive the Nobel Peace Prize in 1931. Jane is widely acknowledged as the first woman philosopher in the history of the US and her essays on peace and ethics are canonical texts in peace studies.

In 1946, in a world still traumatised by the horrors of World War II, Emily Greene Balch emerged triumphant, as she became the first Quaker and third woman to receive the Nobel Peace Prize. An indefatigable activist, she dedicated her life “to the service of goodness” and her life philosophy was that of inter-cultural cooperation. The last entry of this book is of Baroness Bertha Von Suttner, a CzechAustrian pacifist, journalist and novelist, who was also the first woman to receive the Nobel Peace Prize in 1905.

She had inspired her friend Alfred Nobel’s decision to institute the Prize as he wrote in a letter, “The prize would be awarded to him or her who had caused Europe to make the longest strides towards ideas of general pacification.” Bertha believed that universal sisterhood was necessary before universal brotherhood was possible.

Battling Injustice is a wonderful read and an inspirational text and women in the workplace, at home, as mothers and nurturers, as leaders will all find something to take away from this collection, which took the author more than six years of painstaking research and many interviews. The author’s hope in writing this book is to inspire women to rise up, to come to the forefront of all human affairs and help eliminate weapons from the world. All the stories, starting from humble origins, are awe-inspiring yet relatable. It should also inspire men to forget patriarchal domination and lend support to their womenfolk who are striving for justice and to make the world a better place to live in.

(The reviewer is professor of English at Visva-Bharati University)

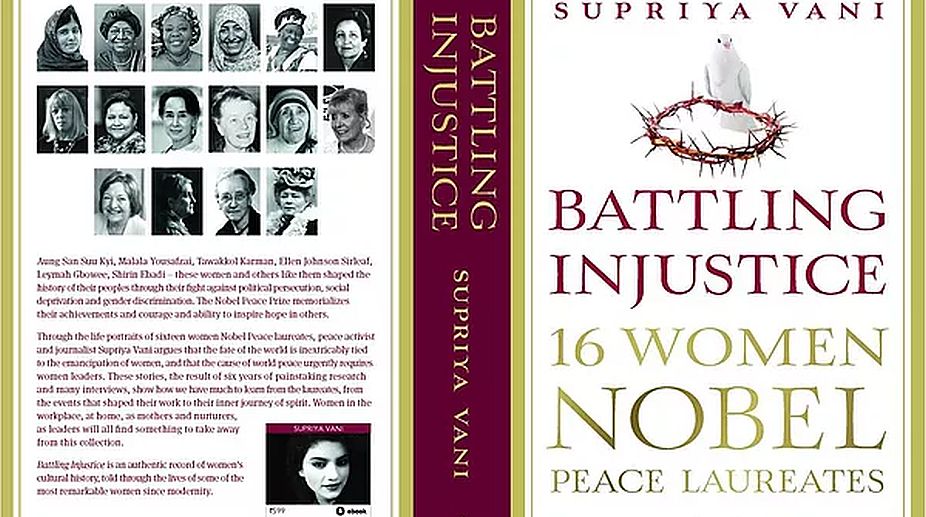

BATTLING INJUSTICE: 16 WOMEN NOBEL PEACE LAUREATES

By Supriya Vani

Harper Collins, 2017