In search of Indianness

India’s cultural consciousness is embedded with pearls of heritage carried forward through generations in the form of folk art.

While Valmiki speaks of one Ravana, in subsequent tellings of Ramakatha, we find several Ravanas, each more powerful than the others, most of them more monstrous and gruesome, including a Ravana with one hundred thousand heads instead of the ten heads we are familiar with!

One other major change we notice in these tellings is the change in the stature of Sita. While some tellings make her softer and more delicate than she is in the Valmiki Ramayana, some of them make her far more powerful. In many of these new tellings, she frequently replaces Rama as the true source of power, as someone who can do, sometimes effortlessly, things far beyond Rama’s capacity.

Hanuman is already the accomplisher of impossible deeds in Valmiki’s Ramayana. But with each subsequent telling of his story he grows, to become a doer of even more awesome and impossible deeds.

Advertisement

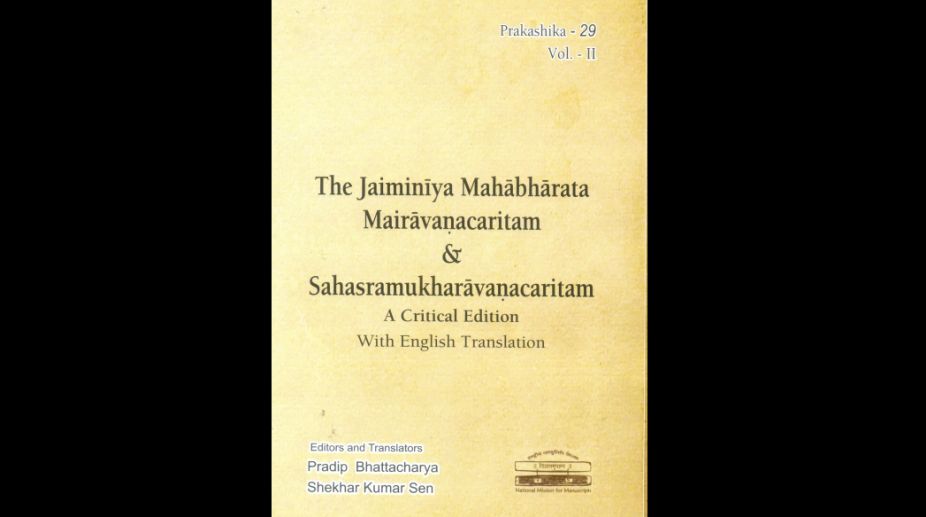

The Mairavanacharitam and Sahasramukharavanacharitam are two such books that tell, respectively, the story of the encounters between Hanuman and Mairavana and between Sita and Sahasramukha Ravana. The books in Sanskrit, recently discovered in Grantha Tamil script, have been critically edited with an English translation by Pradip Bhattacharya and Shekhar Kumar Sen and have been published in twin volumes as The Jaiminiya Mahabharata Mairavanacharitam and Sahasramukharavanachatiram

The texts claim to be parts of the lost Mahabharata narrated by Jaimini — instead of, Vaishampayana whose narration of the Mahabharata is what we are all familiar with — of which only the Ashwamedha Parva survives.

In the Ashramavasa Parva of the Jaiminiya Mahabharata, in the context of narrating the story of the battle between Arjuna and his son Babhruvahana, Jaimini compares it to the ancient battle between Rama and his sons Kusha and Lava. Janamejaya, who is listening to the narration, asks for the details of this ancient battle and Jaimini narrates it at length. This is what is known as Sahasramukharavanacharitam — the Story of Ravana with a Thousand Faces — also known as Sitavijaya, because it is the story of Sita’s victory over Sahasramukha Ravana. When five sons of Durvasa start terrorising the gods, including the trimurtis — Brahma, Vishnu and Shiva — pray to Goddess Yogamaya, the supreme cosmic power from whom the universe emerged into being. Yogamaya assures the gods of her protection. She promises them that Vishnu will be born in human form on earth and she shall be born as his wife and then, “first slaying Dasanana/later I will succeed in slaying Sahasramukharavana.”

It is this Yogamaya that is born as Sita while Vishnu takes birth as Rama and kills the ten-headed Ravana. When Sahasramukha Ravana learns of the death of Dasanana, he abducts Bharata and Satrughna while they are asleep, mistaking them for Rama and Lakshmana. The demon marries his two daughters to them but keeps them in his palace. Rama informed by the gods and urged by them to kill Sahasramukha goes to his city, Visala, along with Hanuman and his army of humans, monkeys and Rakshasas. The gods join them. But all of them together are no match for Sahasramukha, including Brahma, Vishnu and Shiva. He beats them all in a brutal fight.

Sita is seated on the Pushpaka watching it all, her heart filled with grief at the fall of her husband and the gods. The heavenly sages now praise her as the One Goddess Who is All.

You are Svaha! You are Svadha!

O Devi, you are

Sri, Pushti, Sarasvati,

You are Rudrani, Visalakshi, Tushti,

Medha, Dhriti,

Kshama!

After singing her praises, they request her to bring the gods back to life. She promises the sages to do so and assumes her wondrous form. In the meantime, Hanuman regains consciousness and is astonished to see the amazing form of Sita. Sita tells him:

By my grace, hanuman, you will become

Five-faced.

Your strength will be unbearable for foes

In battle.

Instantly Hanuman becomes five-faced — he now has the faces of a lion, a horse, Garuda, and a wild boa — apart from his own monkey face. Sahasramukha Ravana now wants to kill Sita and a fierce battle ensues between the two. Such is Sita’s might that she uses not proper weapons to fight the demon but darbha grass. She swallows Sahasramukha’s awesome missiles empowered by Sage Durvasa’s ascetic power and aims darbha grass blades at him, which become mighty columns as they speed towards the demon.

Seeing those flaming grass-columns, “the Lords/of the celestials/fearing cosmic dissolution were afraid / The seas were in turmoil then /Mountains shattered, the earthquaked.”

At the attack of Sahasramukha, the grass columns splinter into a thousand fragments, which the demon swallows. Inside his belly the flaming fragments reunite and the furious fire reduces him to ashes.

The trinity and other gods now propitiate Sita. Brahma sings her praises, calling her “Maya, Vaishnavi, Durga, Lakshmi, Gauri, Saraswati, Svaha, Svadha, Dhriti, Medha, Hri, Sri…Varahi, Bhadrakali” and all other goddesses. Requested by him, Sita withdraws her effulgence into herself and once again becomes human, womanly bashfulness appearing on her face. Hanuman too withdraws his five-faced form and appears in his normal form.

Mairavanacharitam Sahasramukharavanacharitam is the second book of the twin volume set, the first and shorter volume being Mairavanacharitam, also called Maruti-Mairavanacharitram. What the book essentially does is glorify Hanuman and his amazing powers and deeds. The story begins towards the end of the Ramayana war when Ravana is still alive, but has lost all his mighty rakshasa combatants. He thinks of Mairavana, the ruler of the nether world who instantly comes to him.

Pradip Bhattacharya and Shekhar Kumar Sen have located the manuscripts of the two works, got them transcribed from Grantha Tamil to Devanagari and then critically edited them to arrive at texts as complete as currently possible. The editors have then translated the works into English, keeping as close to the syntax of the original text as possible. This is work that requires great dedication, total commitment, true scholarship and an immense amount of hard work. The literary quality of the original Sanskrit texts is not great, nor is there complete consistency in the narration, as the editor-translators point out in their long and very valuable introduction. The author of these two works, Jaimini, seems to have had a “somewhat casual attitude” towards them. Though the works are claimed to be that of Jaimini, this Jaimini seems to be different from the famous Jaimini, one of the five disciples Sage Vyasa.

While the two stories are fascinating, the dominance of magic in them take the books closer to what we call tilismi literature, like the legendary Chandrakanta and Chandrakanta Santati in Hindi, rather than to the Indian epic tradition.

The translation is consistently outstanding, which is not always the case when it comes to translating Sanskrit verse into English verse. The great mastery of the editor- translators over English language and literature is certainly one reason behind it.

Keeping the translation as close in syntax to the original text has its own charm. The translators need to be congratulated for achieving this difficult task. In a few places I found the translation can be improved — like darbha is not just grass but sacred grass, padapa means plants as well as trees (and grass too, strictly speaking), though in one place it has been translated as plant where the text means tree (Ch 47.51). In chapter 48, when Brahma praises Sita, he calls her “Sakhi ofBrahmana and Vasudeva”. In the original Sanskrit it is brahmano vasudevasya sakhi, meaning a friend of Brahma and Vasudeva. In the Sanskrit text of the same verse, durjneyavaibhavaa (one whose glory cannot be easily known) should be one word instead of two and so on.

These minor drawbacks do not in any way reduce the immense significance of the splendid work done by the editor-translators. What they have done is to make a superb contribution to the study of ancient Sanskrit literature, and the fact that they discovered the text and saved it from oblivion makes their work all the more praiseworthy.

This is a truly masterly work for which all lovers of Ramakatha studies, Sanskrit literature and Indian culture will remain deeply indebted to the scholarly editor-translators.

The reviewer is management professor, corporate trainer, author of numerous articles on Indian psychology, spirituality, culture, epics, Upanishads and the Bhagavad Gita

Advertisement