Ben Kingsley and his role as Imdad Khan

You might recall Ben Kingsley’s iconic portrayal of Gandhi in the 1982 film. Well, this versatile actor Ben Kingsley is…

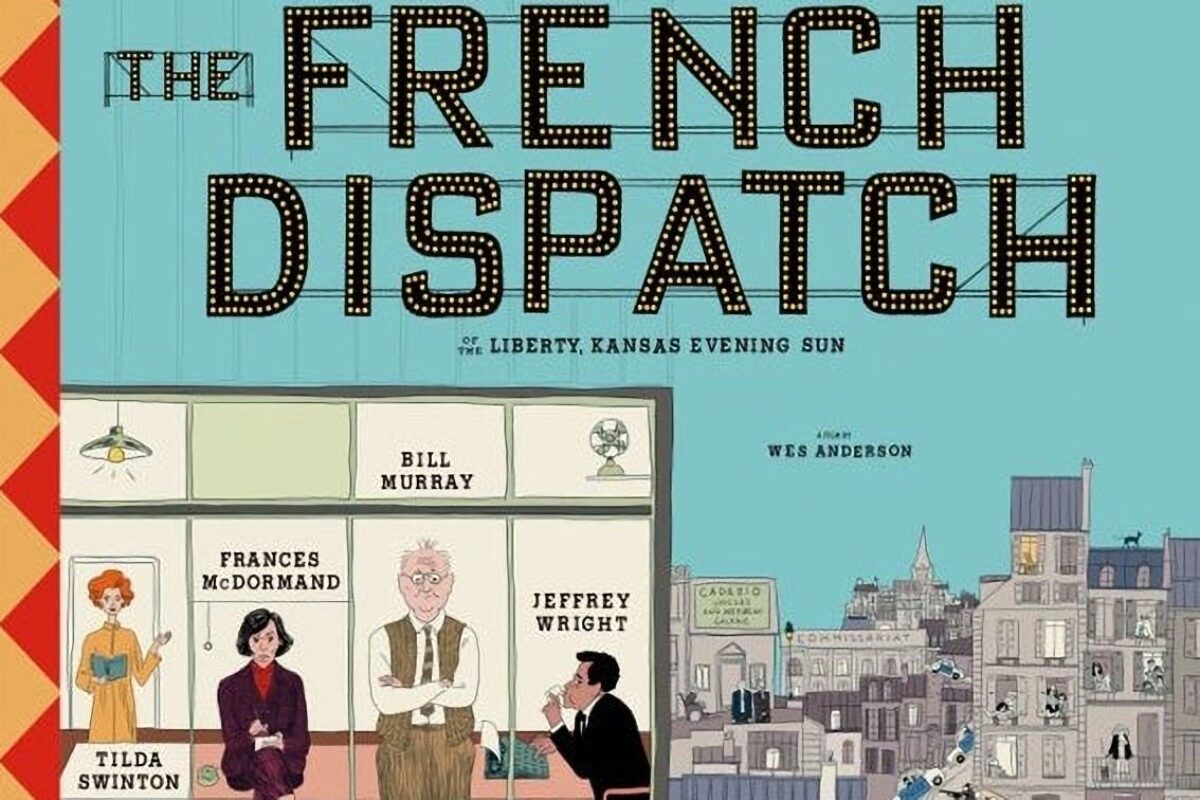

Filmmaker Wes Anderson’s The French Dispatch is a love letter to the glorious highs of print journalism and foreign correspondents

The French Dispatch by Wes Anderson

If ever a film gave viewers the feeling of reading the supplementary page of a newspaper with its assemblage of witty articles, sophisticated humour and artistic panache, then it is Wes Anderson’s The French Dispatch. A satirical comedy that celebrates the halcyon days of print journalism and the world of foreign correspondents, it is set in 1960s France.

The French Dispatch is Anderson’s homage to the New Yorker, an American magazine, which since its inception in 1925, has impressed readers with its distinctive cartoons and a variety of pieces on politics, gossip, art, fashion and food. The film boasts a host of eminent actors as part of its cast — Benecio del Toro, Tilda Swinton, Frances McDormand, Lea Seydoux, Adrian Brody, Owen Wilson, Bill Murray, Timothée Chalamet, Christoph Waltz, Willem Dafoe, Edward Norton and Mathieu Amalric, among several others.

A deranged convict with an artistic flair, a misdirected students’ revolution born of raging hormones, a city of paradoxes, a French police commissioner’s sous chef and the obituary of an editor — these are some articles from the fictional “French Dispatch”. It is a feuilleton of an imaginary Kansas-based newspaper, published out of its French bureau in an imaginary city called Ennui-sur-Blasé (literally, “boredom on jaded”) that “rises suddenly on a Monday”.

Advertisement

The film is a set of reports by the supplement’s correspondents for the final edition of the magazine before it shuts shop following the death of its proprietor and editor. A strange predicament assails the reporters who are assigned to write pieces beyond their general beat topics, at times, by editor Arthur Howitzer Junior. His sole advice to them is, “However you go about it, try to make it sound like you wrote that way on purpose”.

For the article “The Cycling Reporter”, correspondent Herbsaint Sazerac pedals down the streets of Ennui-sur-Blasé in search of poetry amid a prosaic landscape where rats inhabit subterranean railroads, cats colonise slanting rooftops, and “anguillettes” swim along shallow drainage canals. He remarks that the city, during its lengthy existence, evolved with new identities as the names of its typical places changed with the passage of time. The butcher’s arcade is no more a grotesquely posh “Passage des Bouchers” but an inanely brutish “Metro Abattoir”.

The editorial stance often leads to hilarious outcomes. Case in point is a piece by a crime correspondent called Roebuck Wright, who, in exchange for his bail from a local police station, is assigned to profile a ranking chef, employed with the police commissioner with whom he is to have a private dinner. With the incidents of that night leading eventually to a crime, Wright fails to shrug off his instinctive crime reporting style and smuggles in gastronomic terms!

Here is a glimpse of the comical consequences as Wright describes the interior of the bustling police headquarters where he struggles to find his way to the private dining room of the commissioner, “Police cooking began with the stakeout picnic and paddywagon snack but has evolved and codified into something refined, intensely nourishing and if executed properly, marvellously flavourful. Fundamentals: highly portable, rich in protein, eaten with the non-dominant hand only, the other being reserved for firearms and paperwork.”

Passing through the “Disguises” department, stacked with clothes, two insipid officers, and a creaking police radio, he remarks “Most dishes are served pre-cut. Nothing crunchy. Quiet food. Sauces are dehydrated and ground to a powder to avoid spillage and the risk of tainting a crime scene.”

In the “Arts and Artists” section, art correspondent J K L Berenson pens a story about a mad convict with an artistic flair for painting pieces of “modern art”; even if they are etched on prison walls and need to be carved out for an auction! She titles it, “Ten reinforced cement aggregate loadbearing murals”.

It is unlikely that anyone before Anderson painted such a chic satire on the “May 68” students’ protests in Paris. Two campuses of Paris University, Nanterre and Sorbonne, are said to have raised a storm of Leftist protests, which was later suppressed with police action but nonetheless, became a part of French legacy. Lucinda Krementz, political correspondent of “The French Dispatch”, in her report “Revisions to a Manifesto” describes a similar student revolution stirred by the “pimple cream” and “wet dream” contingents of “Universite Superieure D’Ennui”. The soixante huitards in her report are fighting out of a biological need for freedom that involves the right to access the women’s hostel!

Shot in Angoulême, France, the film unfolds in Anderson’s art nouveau style with a meticulous symmetry. Rarely has the nuances of print journalism looked so attractive and its correspondents so sassy. Chasing deadlines, clacking typewriters, editorial meets, rapid pen strokes of disapproval, “grammar Nazi” sub-editors, correspondents and their world of stories — in its luscious pastel colours and monochromatic frames, the film is a kaleidoscope of dreams.

For those who were fortunate enough to have witnessed the highs of Indian print journalism in the late 1960s to 1970s, “The French Dispatch” will serve as a nostalgic recollection of the colourful, peppy and witty “Junior Statesman”. Later rechristened “JS”, it was a popular magazine of this newspaper, conceived by its last British editor Alfred Evan Charlton. It remained in the hearts of its subscribers who refused to bid farewell even when it finally shut down. Those articles in “JS”, often accompanied by the legendary Desmond Doig’s sketches, went on to become a manifesto for the cosmopolitan youth of the time.

Coming back to The French Dispatch, references are aplenty in Anderson’s movies and one can never fail to applaud the wry humour. Nothing in the film leaves one in ennui as it mines even the dreariest of subjects to tickle the funny bone. Anderson ensures that his motion picture magazine sinks deep into one’s mind as it plays out in a rhythm amplified by the touching music. Sometimes certain scenes may seem bereft of pace, but they are never boring. After watching the film, one craves a hard copy of “The French Dispatch” even if it’s just to be kept as a memento.

The French Dispatch is available for viewing on Disney Hotstar.

(The writer is a reporter, The Statesman, Kolkata)

Advertisement