Whiff of mismanagement in Bangiya Sahitya Parishad

The annual general meeting of Bangiya Sahitya Parishad is going to be stormy in view of the sheer mismanagement of the authorities running the organization.

There can be various points of disagreement with Rabindranath Tagores critical juxtaposition of Kalidasas Abhijyan Sakuntalam and William Shakespeares Tempest.

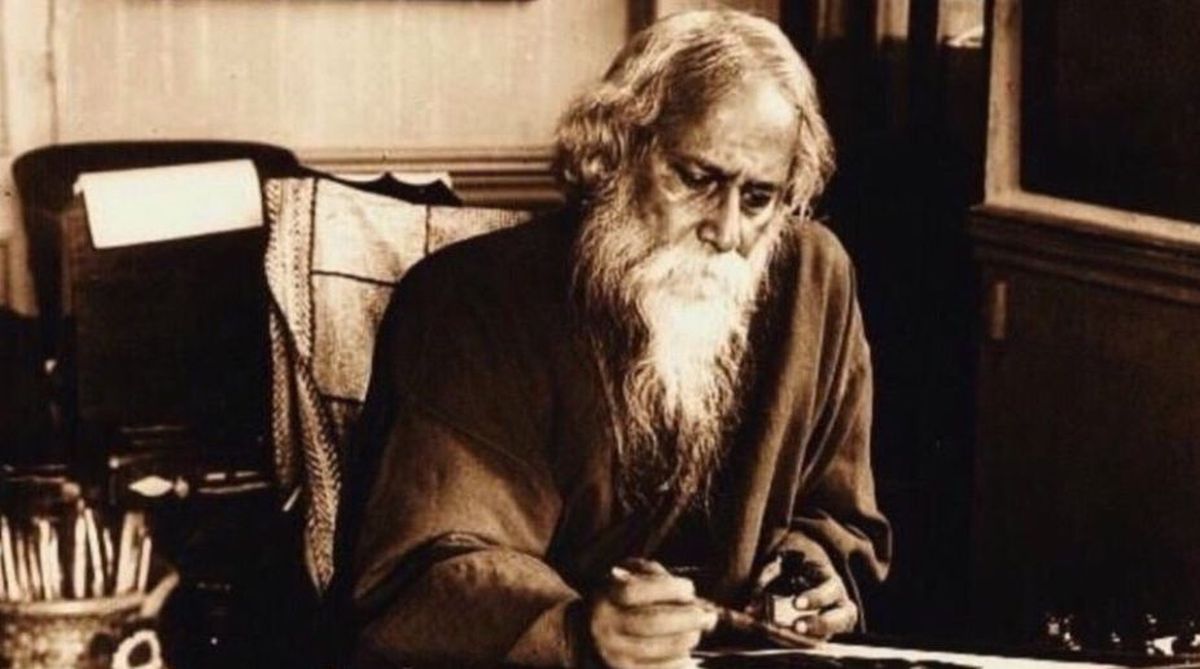

Rabindranath Tagore.

It was actually Kalidasa’s Abhijyan Sakuntalam that took me to the world of Tagore’s prose. The one I was looking for was there in a collection of essays named Prachin Sahitya. It consisted of several essays written on subjects like The Ramayana,Meghdutam,Kumarsambhava, Abhijyan Sakuntalam, Kadambari and “Ignored by the Poets”. It was just a fantastic find for me.

They were indeed path-breaking essays not only because they showcased Tagore’s talent as a writer but also because they explicated his adeptness and ingenuity in handling a comparatively new critical form —the art of comparative literary criticism, almost unknown till then, in Bengali literature.

My specific interest lay in the essay on Abhijyan Sakuntalam. It’s an interesting case study for several reasons. But I prefer to discuss Tagore’s modus operandi. Prior to him, only Bankim Chandra Chatterjee had initiated the trend; but Bankim’s works were limited. It was actually with Tagore that the art developed and flourished. Tagore’s clarity of thought and rationality of argument became the template for later Bengali critics.

Advertisement

In this essay, Tagore makes a comparative study of Shakespeare’s The Tempest with Kalidasa’s Abhijyan Sakuntalam; indisputably an exceptional venture. However, the point of contention is Tagore’s point of view. Unlike his predecessor Bankim, Tagore’s stance is neither impartial nor objective. Actually, Tagore’s biased critique of Shakespeare is surprising.

First of all, the name — Prachin Sahitya (Ancient Literature). Historically, Shakespearean plays are ancient, but contextually they are still modern. Kalidasa’s Abhijyan Sakuntalam, despite its poetic beauty, is certainly an old mythical play whose relevance has been lost. Moreover, was Shakespeare really as ancient as Kalidasa?

Abhijyan Sakuntalam was written during the famous Gupta Dynasty in 320AD; when the political scenario of the world was very different from the world of Shakespeare. In fact, at that point of time the concept of English literature didn’t really exist. Expectedly, Kalidasa’s approach was bound to differ from Shakespeare. When Shakespeare wrote The Tempest (approximately around 1623) the world had undergone spectacular changes. England had come into being and English writers were practicing their arts. Politically the world was fragmented according to race, culture, religion and even colour. And, 17th century in the European context was adjudged the beginning of the modern era.

Therefore, is it fair to presume The Tempest to be dated? Academically or otherwise, the theme of the play, usurpation and forcible occupation, is not only extremely contemporary but is still relatable in the modern world. Hence, logically it should neither be relegated as ancient, nor redundant. In contrast, Abhijyan Sakuntalamthough discussed in the academic circles remains confined to a few Sanskrit scholars. Reading and comprehending the original version of the play is a near impossible feat.

Then follows thematic substantiality. Though not clearly stated, to Tagore The Tempest, in comparison to Abhijyan Sakuntalam was by and large a superficial representation of life. “The Tempest does not encompass the enormity of Abhijyan Sakuntalam’s range of experiences…. the delineation of Miranda is also superficial in contrast to Sakuntala”. However, in a stray comment, Tagore mentions the different settings of the two plays, leading to such deviations. But he does not explicate it further. How could Tagore miss out this basic premise that the differences were actually based on technicalities and not themes?

Most of the European plays then, scrupulously followed the rules promulgated by Aristotle’s Poetics, which divided plays into two distinct genres —comedy and tragedy. There was no provision for their interfusion. Moreover, with fixity of time, place and action, the playwrights did not have much scope to present a large canvas of human lives. Actions were limited to one or two specific events. Thus, their writings appeared rather fragmented or sliced in contrast to the Sanskrit plays, where presentation of a totality of human life was mandatory. Tagore was possibly referring to this technical difference as thematic insubstantiality. So, Shakespeare unlike Kalidasa, had to restrict himself both thematically and structurally, to a reduced canvas.

A cursory glance at Bharat’s Natyasastra, is required, before we proceed. According to Bharat, sliced or fragmented representation of human life in a play was a strict no, no. So, Sanskrit playwrights could space out their stories as much as they wanted. Furthermore, ancient Sanskrit plays were a conglomeration of multiple experiences of human lives, both joyful and sad, as the very concept of tragedies and comedies was unheard of.

But the European plays, being structured on Aristotelian precepts, remained satisfied with fragmented projection of human lives, compartmentalised as either happy or sad. As a result, the question of presenting a totality of human experience did not really arise. Their works could either portray the joys or sorrows existing in human lives, and not a mixture of both. It was therefore just a technical divergence, not qualitative inferiority as Tagore conjectured.

Tagore goes on to explicate the peripheral similarities between the protagonists of the plays – – Sakuntala and Miranda. Both are beautiful young girls, fostered far away from the intricacies of the so-called civilised societies.

Sakuntala is under the tutelage of Sage Kanvya in his hermitage, in the fringes of a dense forest, while Miranda’s father Prospero, deprived of his kingdom, perforce remains exiled in a remote and uninhabited island.

But, unlike Kanvya, Prospero is not an ascetic. He was a ruler before his brother usurped his throne, and his aspiration to win back his lost kingdom is still strong in him. However, both girls lost their mothers right after birth. Maneka, a courtesan of heaven, was Sakuntala’s mother. She had conceived Sakuntala in a relationship with Sage Viswamitra. But immediately after delivery, Menaka had left Sakuntala in the care of Sage Kanvya and returned to heaven. Sakuntala remained with her foster father and was looked after by an elderly lady of the hermitage. So Sakuntala had a foster mother. But Miranda was not only banished from her birthplace, but had also lost her mother right after her birth.

The entire onus of her upbringing was shouldered by her biological father, Prospero. She had no feminine touch in her life. Furthermore, both Prospero and Miranda had journeyed a rough sea to reach an unnamed island to survive. Other than these minor differences their tales are more or less similar.

It’s a case of love at first sight for both of them —Sakuntala falls in love with King Dushyanata when she sees him entering Kanvya’s hermitage, while Miranda falls in love with the shipwrecked Ferdinand, when he manages to swim to their island. According to Tagore, these similarities are external and restricted to accidental occurrences only; but when it comes to the question of their inner beings, Sakuntala and Miranda are poles apart.

The problem lies with the conjectures of Tagore. Quoting Goethe, Tagore says, “If a person desires to observe the flowers of youth and ripened fruits of old age; likewise, if someone desires to conceptualise heaven and earth together, it is to be found in the play Sakuntala”.

Goethe’s conjecture is absolutely correct but not Tagore’s inference. For Tagore, thematicallyAbhijyan Sakuntalamis an all-encompassing play while The Tempest is just a sliced one. True, The Tempest presents only a part of the lives of both Miranda and Prospero, while Abhijyan Sakuntalam covers the entire gamut of Sakuntala’s life. Clearly this happened because Kalidasa was strictly following the rules of the Natyasastra and had the liberty to portray the entire workings in Sakuntala’s life. But Shakespeare had no such license.

The Tempest if analysed contextually clearly emerges as a realistic documentation of the colonial maladies as Shakespeare had perceived — Prospero’s forcible acquisition of the island from Caliban. While Kalidasa had no such political scores to settle; his linear plot is more in line with the mythical antecedence of his characters with tragic undertones.

Interestingly, Tagore doesn’t talk about the structural qualities of the two plays —the basic requisite in literary criticism. To him poetic quality is of prime importance. But poetry does not sanitise technical discrepancies.

Nature plays a vital role in Kalidasa’s play, argues Tagore, “The surrounding (natural) ambience of the hermitage (tapavan) was congenial to the wonderful upbringing of Sakuntala. Artificial social rules or religious regimentation did not prevail here. Yet, people living in the hermitage were extremely religious.”

Nature performs two different functions in the two plays. In Abhijyan Sakuntalam, Nature is subliminal, but in The Tempest, Nature is instrumental for attaining a goal. Thus, right at the beginning of The Tempest, the tumultuous storm plagues a sailing ship. The indication is clear; the turmoil of the sea merely replicates the turmoil at the human level. Even in Abhijyan Sakuntalam the disrupting presence of the King and his followers in the forest, while chasing the deer and decapitating the foliage, is quite in keeping with the political disruption in Dushyanta’s kingdom as seen later. So, Nature is not always subliminal in Kalidasa as well.

Furthermore, Tagore covertly suggests that Miranda, compared to Sakuntala, is far more aggressive in manifesting her love for Ferdinand. But to Bankim, “Miranda’s behaviour is born out of her incarnate innocence. Unlike Sakuntala she doesn’t even realise the real identity of Ferdinand, ‘Lord, how it looks about! Believe me, sir, / It carries a brave form. But ‘tis a spirit… I might call him / A thing divine, for nothing natural / I ever saw so noble’. “

So, the suggested aggressiveness of Miranda is born out of a different kind of innocence. Unlike Sakuntala, Miranda was never exposed to any other human being except her father. She lives in a world of spirits where human beings are mere trespassers; hence, she hardly knows how to react when she meets a human being for the first time. When she meets Ferdinand for the first time, she is merely curious, “Lord, how it looks about! Believe me, sir, / It carries a brave form. But ‘tis a spirit.” Ferdinand for her is just an extension of the world of spirit (it) she is so habituated to. So, when Prospero tries to ascertain her actual feelings she doesn’t dither to admit, “My affections / Are then most humble: I have no ambition / To see a goodlier man.” Unlike Sakuntala, she is neither abashed nor coy. This forthrightness of Miranda is quite in keeping with her upbringing. She has not learnt the art of coyness or abashment.

Kalidasa in Abhijyan Sakuntalam conceives a different set of reactions for Sakuntala. Sakuntala feels shy on seeing Dushyanta for the first time. And this shyness is an acquired response. Sakuntala has learnt it from the inmates of the hermitage. Even though set miles away from the mainstream society, the hermitage had set rules and regulations for the members, in keeping with mainstream society. Thus, when she meets Dushayanta for the first time, Sakuntala spontaneously manifests a maidenly diffidence because she has been taught to avoid male company.

Gradually the feelings of both the girls undergo a sea change. Sakuntala is smitten by Dushyanta and Miranda by Ferdinand. In case of Sakuntala the response is mixed —diffidence coupled with coyness. But Miranda’s reaction is unchanged. She remains her former self even while admitting to Ferdinand, “But my modesty, / The jewel in my dower, I would not wish / Any companion in the world but you.”

Instances such as these are too many to reckon. My conjecture is simple —in the given essay, Tagore, the critic, didn’t live up to the expectations of readers.

Advertisement