‘Tarak Mehta’ fame Gurucharan Singh reveals reasons behind his disappearance

In a recent interview with The Bombay Times, he revealed the real reasons behind his disappearance and claimed that he had no intentions of returning.

The tree is known by its fruits. Buddhism put reason in place of authority, it discarded metaphysical speculation to make room for the practical realities of life, it raised the self-perfected sage to the position of the gods of theology, it set up a spiritual brotherhood in place of hereditary priesthood, it infused a cosmopolitan spirit against national exclusiveness.

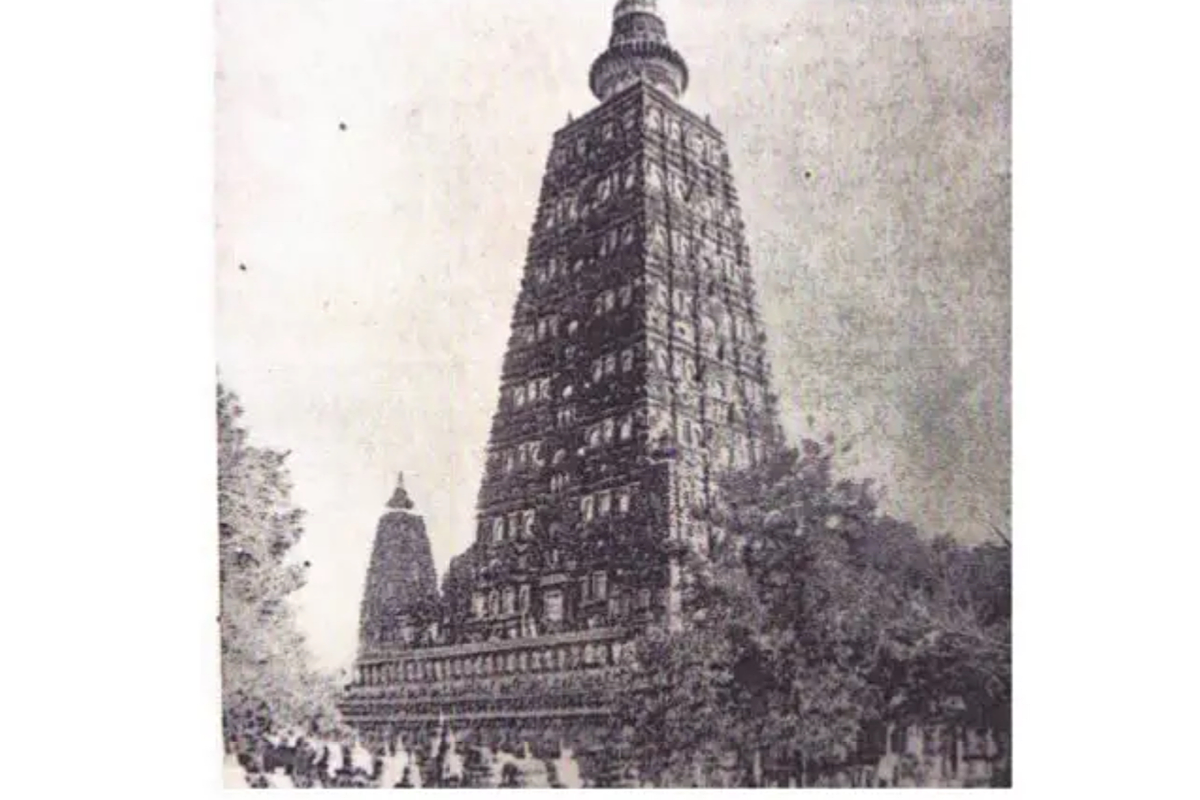

(Photo:SNS)

The tree is known by its fruits. Buddhism put reason in place of authority, it discarded metaphysical speculation to make room for the practical realities of life, it raised the self-perfected sage to the position of the gods of theology, it set up a spiritual brotherhood in place of hereditary priesthood, it infused a cosmopolitan spirit against national exclusiveness.

“Dogma and miracle are wisdom to the Christian; kismet and fanaticism are wisdom to the Muslim; caste and ceremonialism are wisdom to the old Brahmin; asceticism and nakedness are wisdom to the Jain; mysticism and magic are wisdom to the Taoist; formalism and outward piety are wisdom to the Confucian; ancestor-worship and loyalty to the Mikado are wisdom to the Shintoist; but love and purity are first wisdom to the Buddhist … Buddhism alone teaches that there is hope for man and only in man”. (P. Lakshmi Narasu, ‘The Essence of Buddhism’). In the opinion of R.C. Mitra (The Decline of Buddhism in India and its Causes), the historic significance of the rise of Buddhism must be realized in its proper context. This context is that Buddhism never cut itself asunder from the parent stock of Brahmanism and that the great Buddha was a child of that noble culture which is generically known as Brahmanism. Dr. S. Radhakrishnan, a noted scholar of Hindu philosophy, has observed at one place: “The Buddha did not feel that he was announcing a new religion.

He was born, grew up, and died a Hindu. He was restating with a new emphasis the ancient ideals of the Indo-Aryan civilization”. (S. Radhakrishnan, Foreword PP.IX , XIII in 2000 years of Buddhism). P.V. Kane has noted this Brahmanical theory of the origins of Buddhism and has examined and criticized the views. The historical truth is that Buddha had penetrated the Indian mind very deeply; his images had covered thousands of pillars, walls and gates of so many monasteries all over the country; his teachings had been popularised and broadcast through an almost inexhaustible mine of Pali and Sanskrit literature; many emperors and thinkers had espoused the cause of his rational and humanitarian mission, and his praise had been sung by numerous Indians for centuries. He is naturally regarded as the most exalted member in the galaxy of Avatars.

Advertisement

A number of scholars, including S. Radhakrishnan, R. C. Majumdar and others have opined that the most important fact concerning the decline of Buddhism in the country of its origin was a gradual, almost insensible, assimilation of Buddhism to Hinduism. The Mahayana (this form of Buddhism regarded Buddha as God) borrowed heavily from Hinduism, and the latter appropriated many cardinal elements of the former. This mutual rapprochement between Hinduism and Buddhism proved fatal to the latter faith. The disapproval of animal sacrifice, the relaxation of caste rigidities in Brahmanical quarters owing to Buddhistic influence and the organization of a monastic community on the lines of the Buddhist Sangha by Sankaracharya, the standard bearer of Hinduism, may have further helped the merger of Buddhism into Hinduism.

According to G. C. Pande (Bauddha Dharma pp. 491-492), one of the most important factors in the decline of Buddhism in India was its social failure. It did not try to evolve a complete society on its own lines; it did not prescribe any ceremonies for birth, marriage and death of the householder. The laity continued to practice the current norms and ceremonies prescribed largely by the Brahmanical clergy. This non-interfering attitude of Buddhism, though it helped the smooth spread of the religion, resulted in the long run in lessening its hold on society. This aloofness was a serious flaw which confined the Buddhistic culture to the monasteries.These monasteries were the strongholds and the only centres of Buddhistic culture; when they were invaded by indigenous or foreign rulers (especially Turkish) or they lost royal or popular support or when they became deserted and dilapidated by some other calamities, Buddhism started decaying. In such circumstances lay followers of Buddhism who were never made free from the influence of the traditional orthodox culture, returned more and more towards the latter.

The seemingly everlasting strength of Brahmanism (Hinduism) would appear to lie in the fact that its religion and society are inseparable. The fabric of Hinduism rests on the bed-rock of varnasrama organization. It survived even when the Muslims killed its ascetics, pulled down its temples and dishonored its women; it survived in society. Some writers like Umesha Mishra (Journal of the GanganathaJha Research Institute, vol. ix p. 111-122) have opined that one of the main causes of the decline of Buddhism in India was that the Buddhists hated Sanskrit and adopted the Palilanguage. Now, one may ask: how are we to account for the progress and continued existence of Jainism which also adopted Prakrit, a non-Sanskrit language? Furthermore, the Mauryas adopted Pali as their official language, will it not be an absurdity to attribute the decline of the Maurya Empire to their adoption of a non-Sanskrit language?But it is not true to say that the Buddhists hated Sanskrit.

The whole mass of Buddhist literature from about the second century B.C. onwards has been written in Sanskrit and taught its grammar as a compulsory subject in their universities. Decline in the royal patronage of Buddhism is regarded by some modern scholars as the foremost factor in the disappearance of Buddhism from the land of its birth. After all, in those days the religion of the king was, more or less, the religion of the people. It was in the third century B.C. when Asoka extended his patronage to Buddhism and began to preach it both within India as well as to near and far off countries like Burma, Ceylon, Sumatra, Egypt, Macedonia, Syria etc. that Buddhism became a world religion from a local one. In the second century B.C. the Kushana King Kanishka extended his patronage to Buddhism which spread into China, Tibet and Central Asia.

It is true that after Harsavardhana no strong and whole-hearted patron of Buddhism in India is known, except some of the Pala kings. It was during their period the Bengalee savant AtishDipankar was invited to Tibet to effect some reforms in Buddhism. It is, however, to be borne in mind that the Pala kings were patrons equally of the Brahmanical religion. As a result, no king came forth to protect the Buddhists of Sindh when they were attacked by the Arabs; no king’s army came forward to protect Nalanda when it was sacked by the soldiers of BakhtyarKhalji. Buddhist monks either fell before the swords of Islam or fled to Nepal and Tibet. One of the really potent factors contributing to the decline of Buddhism in the country was royal persecution, forceful ill-treatment of the monks and damage to or destruction of their holy establishments by the kings. The greatest of royal persecutors of Buddhism in India was the Huna tyrant Mihirakula. Among the ancient Indian princes, the most notable example of anti-Buddhist Brahmanical fanaticism after PusyamitraSunga, is presented by Sasanka, the king of Gauda.

It is, however, a fact that royal persecution of Buddhism in India was only sporadic and occasional; it was not a regular feature. In the seventh century A.D. the Brahmanical faith faced not only decadent Buddhism but also Islam which had been brought to the south-west coast (Malabar) by Arab merchants and preachers. During this critical period Sankaracharya reformed and strengthened the old Brahmnical religion and this Hindu revival could not be resisted by decadent Buddhism. Lastly, an important aspect of Buddhist contribution in ancient India should be mentioned which lay in the area of social harmony and racial integration on a national scale.

It was through its teaching of social harmony and tolerance that foreign invaders such as the Greeks, Sakas, Parthians, Kushans and Hunas who came to India and settled here in the course of centuries immediately preceding and following the Christian era, were assimilated by Indian society. This was a permanent contribution to social integration and national growth, and it could not have been so easily accomplished in a strictly Brahmanical scheme of social gradation. One may feel tempted to conjecture that had Buddhism been a living and creative force during the medieval centuries, the problem of Hindu-Muslim communal disharmony in medieval and modern India would not have taken such a cruel and diabolical turn as it did.

There is no gainsaying that Buddha’s Middle Path struck a new keynote in India’s religious life ~ a course midway between the rigorism of the Jains and liberalism of the sacrificial Brahmanas. The grateful and enlightened Hindus are aware of India’s debt to Buddhism. It has left an indelible mark on our cultural heritage, particularly on our language and literature, art and sculpture, logic and philosophy and on moral values. Marching through the vicissitudes of history, through the rise and fall of many an empire, Buddhism has lost its hold in the country of its origin since long; yet its basic ideals of peace, harmony, brotherhood and the principle of live and let live have not been lost in India and have been finally legalized and accomplished by the government of the Republic of India in 1949-50. Buddha has been honoured by the Hindus as an incarnation of Vishnu, Christians have canonized him as Saint Joshaphat.

Some Muslim scholars regard him as a spiritual teacher. Rationalists regard him as a great free-thinker. H.G. Wells, the distinguished novelist and historian, assigned to him the first place amongst the seven great men in the world. Tagore called him the greatest man ever born.

(The writer is a former UGC Teacher Fellow and Head of the Department of Political Science, Maharaja Sris Chandra College, Kolkata. Views expressed are personal)

Advertisement