Book booker bookest

Then, in 2002, the Man Group stepped in as the sponsor, and the prize came to be known as the Man Booker. The Booker Prize Foundation remained the managing body.

Dwelling upon the mysticism in his poetry, William Blake can be aptly called a spiritual Orientalist who once famously declared that he had an Eastern soul. The universal consciousness and cosmic vastness lent profundity to his craftsmanship.

Mark Edmundson, a professor of English at the University of Virginia, writes if Blake were to recast “London,” probably his best-known poem, for the uses of the present, the poet might be inclined to re-title it “New York” or “Washington”.

Here the question pops up, what prompts professor Edmundson to make this statement about Blake in 2010 when the poet was engaged in the pursuit of writing almost 200 years ago? Those who have seen the sordid underbelly of modern day New York and Washington and understand the symbolic aspect of Blake’s much talked about poem “London”, will definitely be able to establish the connect by putting the dots together.

Wandering through the streets of London, a brutal realisation dawns upon the poet, when he witnesses the gruesome sights of misery spread all about.

Advertisement

The poet feels inexplicably agitated and irate over the rampant prevalence of multiple social evils and rank corruption in religion.

Blake is tragically and painfully aware of the fetters that incarcerate man and finally smother his living spirit to death. He vividly sketches the ghoulish spectacle of his times and laments the predicament of a man who is shackled from head to toe in the mind forged manacles.

Hence, “London” is not a mere geographical entity.

As macrocosm in microcosm, the city of London symbolises the spiritual bankruptcy and moral deprivation, which have percolated down to all the segments of human life. Inarguably, critics recognise Blake and put him on quite a lofty pedestal for the mystic elements in his oeuvre but the fact cannot be refuted that Blake was also a social maverick, a renegade at heart and an iconoclast in his beliefs.

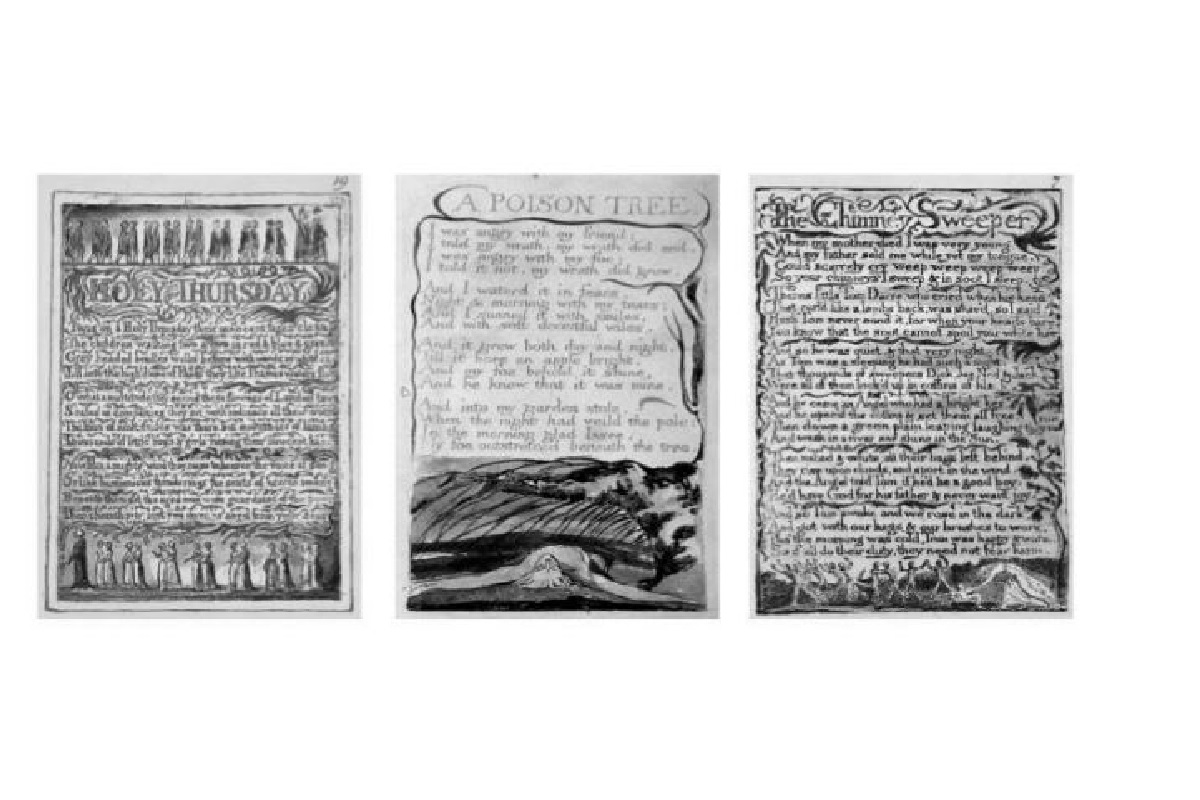

The poems enshrined in his second anthology, The Songs of Experience are an outcry of a man who is doubtlessly displeased and exasperated with the contemporary conditions. Another well-known poem “The Chimney Sweeper” is a sardonic satire on the scourge of child labour.

Putting the poem in the social context, we understand that it was the age of Industrial Revolution in England, which had undoubtedly brought a plethora of prosperity to the privileged strata of society but it had simultaneously hit a final nail in the coffin of the downtrodden.

Many poor innocent children of tender age had to work in the hazardous conditions of mills and factories where they would be pushed into those deadly funnels and chimneys due to their lean and sleek physical structure. Not only disgruntled with this rabid social injustice, Blake also drags divinity in dock when he satirically addresses God a great king who had made up this “ heaven” of miseries for the hapless children. Continuing with the same string of thought about the plight of children, in his poem “Holy Thursday” Blake severely indicts the society that allows children to survive on charity.

The poet speaks of “babes reduced to misery” and “fed with cold and usurious hand”. There is unending winter in the life of these children.

Here, the question is pertinently raised how can a nation claim to be a “rich and fruitful land” when its children are starving to death and many of them have to wait for the two square meals a day from the so-called benefactors of society? Dwelling upon the mysticism in his poetry Blake can be aptly called a spiritual “Orientalist” who once famously declared that he had an Eastern soul.

That is the reason Blake’s approach to poetry was Upanishad-related. The universal consciousness and cosmic vastness lent profundity to Blake’s craftsmanship. He believed in Adi Shankara’s NonDualism (Advait) and was moved by Eastern exclamation, Aham Brahmasmi (I am the Truth). “An amanuensis, I write when God moves my hand,” Blake wrote to Rudolph Glenns, to whom he bequeathed his poetry. While writing his poem, “A Poison Tree”, Blake felt that God was writing through him.

Though metaphysical in nature, Blake did not believe in employing private symbols and metaphors. Very few are aware that Blake knew excellent French and wrote a French poem in 1821 eulogising two seemingly contrasting characters: John Keats and Napoleon Bonaparte, both breathed their last in 1821. That poem can be seen and read at Louvre, Paris.

He wished that Napoleon should have used his pen more than he used the bayonet. An irenic poet to the core, Blake was a pacifist and shunned violence of all sorts. He drew his philosophical insights from Buddha and Lao Tse. It would not be wide off the mark to mention that Gerald Manley Hopkins and Blake inspired Tagore’s 103 poems in Gitanjali that got him the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1913.

Therefore, the indelible imprints Blake has left in the realms of literature can never be obliterated.

Advertisement