Aparshakti Khurana’s ‘Berlin’ surpasses 50m watch minutes in just 3 days

The thriller-drama showcases Khurana's versatility in a standout role as a sign language expert, with strong viewer and critical acclaim.

Thirty years after the fall of the Berlin Wall, we can analyse how the world changed as a result of this singular event that resulted in the reunification of Germany, the collapse of the Warsaw Pact, the Soviet disintegration and an end to the Cold War.

Photo: SNS

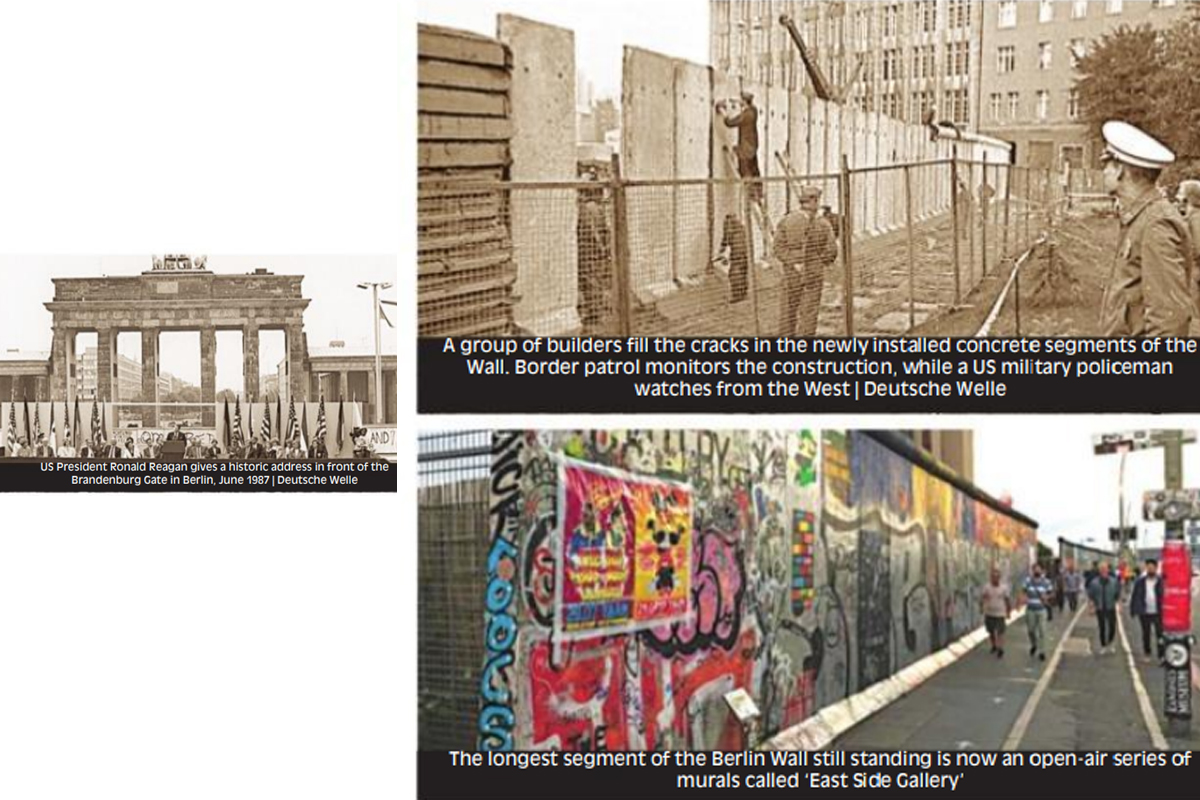

Speaking at the Brandenburg Gate in the western part of Berlin on June 12, 1987, US President Ronald Reagan made a historic statement: “Behind me stands a wall that encircles the free sectors of this city, part of a vast system of barriers that divides the entire continent of Europe … Standing before the Brandenburg Gate, every man is a German, separated from his fellow men…As long as this gate is closed, as long as this scar of a wall is permitted to stand, it is not the German question alone that remains open, but the question of freedom for all mankind …” General Secretary Gorbachev, if you seek peace, if you seek prosperity for the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe, if you seek liberalisation, come here to this gate. Mr Gorbachev, open this gate! Mr Gorbachev, tear down this wall!”

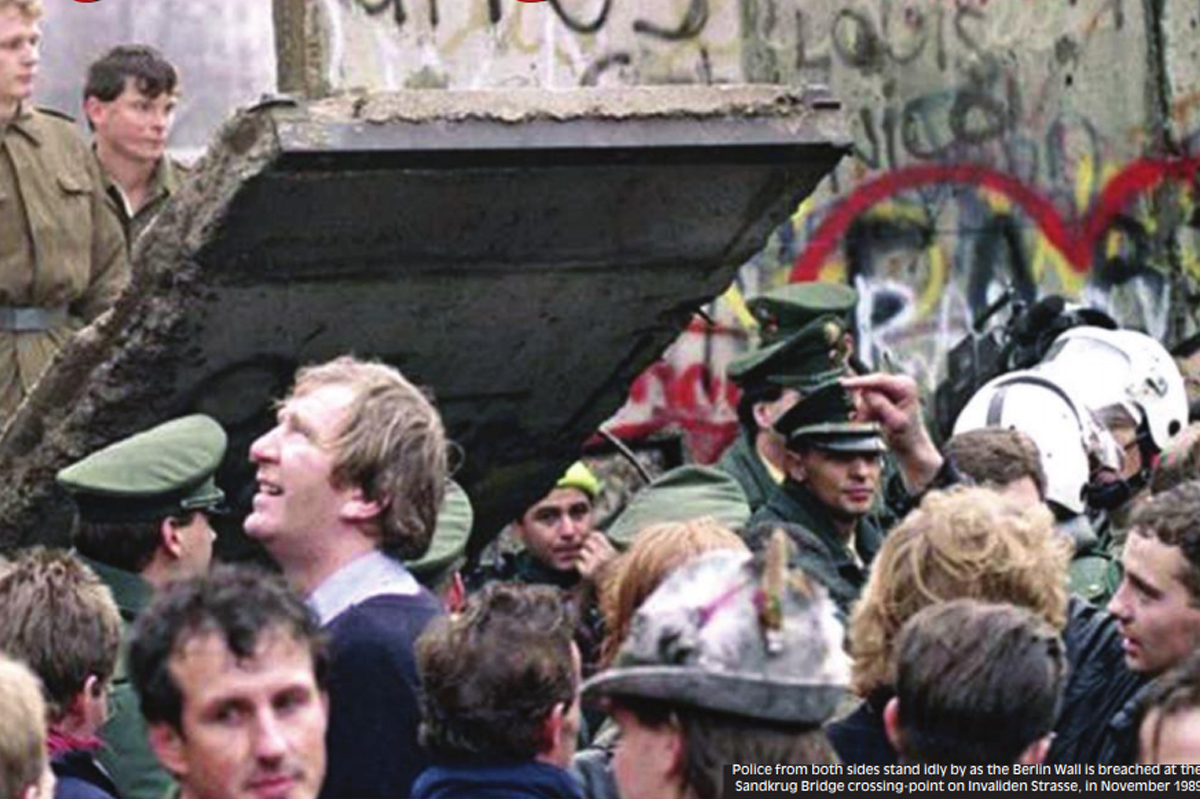

Two years after President Reagan’s passionate speech, the Berlin Wall collapsed. On November 9, 1989, thousands of people from East Berlin forced the East German security forces to let them cross the wall, leading to the ultimate collapse of the Warsaw Pact.

Construction of the Wall

Advertisement

At the end of World War II, the defeated Germany was split into four “Allied Occupation Zones” through the Allied peace conferences at Yalta and Potsdam. The eastern part of the country came under the control of the Soviet Union, while the western part went to the US, Great Britain and France. Even though Berlin was located entirely within the Soviet part of the country (about 100 miles from the border between the eastern and western occupation zones), the Yalta and Potsdam agreements split the city into similar sectors.

The Berlin Wall was erected in August 1961 by the German Democratic Republic (GDR) – the pro-Soviet East German government – to prevent the escape of East Berliners to West Berlin, though the official purpose of the wall was to keep Western “fascists” from entering East Germany and undermining the socialist state. Earlier, the wall only covered the divided city of Berlin, but later it was extended to a dividing line between East and West Germany. It covered a length of 155 kilometres in the form of a concrete wall and fence. However, this symbol of tyranny, oppression and division of East and West Germany by force, failed to deter those who wanted to cross it and escape to the western part of Berlin. Between 1961 and 1989, around 150 people who tried to cross the wall were killed by the East German security forces. Tunnels were also dug from East Berlin to help people attempting to escape communist rule.

Thirty years after the fall of the Berlin Wall, we can analyse how the world changed as a result of this singular event that resulted in the reunification of Germany, the collapse of the Warsaw Pact, the Soviet disintegration and an end to the Cold War. A process of change was set in motion in Europe and throughout the world.

However, the fall of the Berlin Wall failed to have any meaningful impact on some countries where walls have been built, or are being built, to prevent cross-border movement in the name of national security. India constructed a wall/fence along its border with Pakistan all the way from the Rann of Kutch to the Line of Control (LoC) in Kashmir, while Pakistan built a wall on its border with Afghanistan. US President Donald Trump is determined to construct a wall along the US borders with Mexico in order to prevent illegal migrants. Israel has built a wall in the occupied West Bank in order to separate Jewish settlements from the Palestinian population. The need for protecting borders from terrorists, smugglers, the illegal influx of people and national security have led to policies which focus on dividing instead of uniting people across borders.

It would not be wrong to say that walls reflect an insecure mindset, based on mistrust, suspicion and paranoia. From 1961 till 1989, as the Berlin Wall became a symbol of suppression and denial of freedom to the people of East Germany, West Berlin became a symbol of defiance and resistance against the communist order during the Cold War.

What led to the fall of the Wall?

In the late 1980s, Gorbachev’s policy of reforms to liberalise communism – such as Perestroika and Glasnost – gave an impetus to popular sentiments in the GDR for tearing down the wall. At the same time, Erich Honecker, secretary general of the German Socialist Unity Party (1971-1989), was forced to quit when he failed to suppress the rising tide of democracy in East Germany. On August 23, 1989, two million people of Latvia, Estonia and Lithuania formed a 675.5 kilometres long ‘human chain’ demanding freedom from the Soviet Union. Moscow did not prevent the massive popular defiance because, by that time, Moscow had given up the Brezhnev Doctrine of November 1968, which warned of Soviet intervention in case of reformist movement in any communist country.

By 1989, the crumbling economy of the then USSR and the strengthening of a pro-reform lobby, led by Secretary General Mikhail Gorbachev in the ruling Soviet Communist Party, gave a clear message to the forces of democracy and change in the Warsaw Pact countries, including the GDR, that state retaliation in the wake of popular uprising was not possible, unlike the crushing of popular revolts of 1956 in Hungary and 1968 in Czechoslovakia.

A worker’s movement in Poland called Solidarity – launched under Lech Walesa – had been crushed by the military, and martial law had been imposed by General Jaruzelski on December 13, 1981. But under popular pressure, Solidarity was also later legalised by the Polish regime and it won multi-party elections in June 1989.

The fall of the Berlin Wall and its implications in today’s world need to be analysed from three angles. First, the defeat of undemocratic and authoritarian regimes, that sustained brutal systems of oppression, received an impetus with the dismantling of the Berlin Wall. But, even after the passage of three decades, it seems that democracy, tolerance and multiculturalism have not been able to take root in former communist societies. In former GDR, the surge of right-wing ultra-nationalism and neo-Nazism is a dangerous sign and a major threat to German democracy.

In 2013, the far-right political party Alternative for Germany (AfD) emerged as a cogent political force with an agenda focusing on anti-migration rhetoric, and a sizeable electoral strength in the former GDR.

Former Warsaw Pact members, such as Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary and Poland, despite being members of the European Union, refused to accept migrants according to the standards set by the European Union (EU). In all the four countries one can observe a surge of right-wing and xenophobic groups who are intolerant to non-white immigrants, particularly Muslims. This means that despite the collapse of the communist regimes of Eastern Europe, the mindset of those in the opposition and in the government has not changed because transformation from authoritarian to a democratic political culture takes time. On the positive side, on August 24 this year, thousands of people marched in the East German city of Dresden to express their opposition to the AfD. Demonstrators raised slogans against the neo-Nazis and right-wing extremists.

Second, the collapse of the Berlin Wall and German reunification gave a thrust to the process of European integration. Without united Germany, it would have been difficult to transform the European Economic Community (EEC) into EU. The elimination of restrictions on the free movement of people, goods, services and capital in the EU only became possible when Germany emerged as an economic powerhouse of Europe. Germany was officially united as a single state on October 3, 1990, a year after the fall of the Berlin Wall. During this time, the West German Chancellor Helmut Kohl held crucial negotiations with Mikhail Gorbachev, the Soviet president and secretary general of the Soviet Communist Party, the French President Francois Mitterrand and the Polish President Mazowiecki for their support for the reunification of Germany. Without the endorsement of Moscow, Warsaw and Paris, it would have been impossible for the West German leadership to give a final shape to the reunification of East and West Germany. The US President George H. Bush also rendered his country’s support to reunify Germany.

In the post-reunification period, France and Germany have emerged as pivotal states of European Union, as their unity has so far worked to keep EU together against all odds. The transformation of EEC to EU on November 1, 1993, according to the historical Maastricht Treaty, was only possible because of the collapse of Berlin Wall. The expansion of the EU, from 12 members in November 1993 to 27 in 2019, has much to do with the reunification of Germany, the collapse of the Warsaw Pact and Franco-German unity.

Third, the euphoria which existed in Germany after the collapse of the Berlin Wall and reunification disappeared with the passage of time. Despite the German government’s investment of around 100 billion euros to end economic and infrastructure asymmetry between the eastern and western parts of the country, feelings of uneven economic development and wages still prevail over the former GDR.

On June 30, 2019, Herbert Knosowski from the Reuters news agency reported that Frauke Hildebrandt, a member of the centre-left Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) and professor of early childhood education at the University of Applied Sciences in Potsdam, suggested that an employment quota should be introduced for the residents of East Germany. A study by the German Centre for Integration and Migration Research in April shows that more than 50 percent of East Germans polled said they backed the proposal. In March this year, the SPD introduced a motion in the Bundestag (German parliament) calling for an East German quota, arguing that the German constitution mandates proportionate representation of civil servants from all states.

It is often argued by the supporters of the reunification that a sense of deprivation in the former GDR is exaggerated, because German Chancellor Angela Merkel is from the former East Germany and the level of development in that part of the country in the last 30 years is unprecedented. Even then, the AfD has been able to take advantage of the frustration and anger, particularly among the youth of the eastern part of Germany, to emerge as a major political force – taking 25.5 percent and 19.9 percent of votes in Saxony and Brandenburg in the European parliament elections held in May this year.

According to a 2016 study, “Who Rules the East?” compiled by the Dusseldorf-based Hans Bocker Foundation, while East Germans constitute about 17 percent of the population nationwide, they hold only 1.7 percent of the top jobs. In the areas of the former GDR, 87 percent of people are East German but they only fill 23 percent of high-level positions such as judges, generals, presidents of universities, CEOs and editors-in-chief among others. Of some 200 generals and admirals in the military, for example, only two are East German while there are no East German university presidents anywhere in the country.

Reint E. Gropp, president of the Halle Institute for Economic Research, in Halle, an East German town states: “A lot of us thought, admittedly somewhat naively, that people between 30 and 50 – the generation that was already working during reunification – would be affected. But that was a mistake. The effects are transferred through generations and we still see it today.”

Although the quality of life in the GDR was quite low compared to their counterparts in the Federal Republic of Germany, the state was responsible for providing jobs, housing, health facilities and public transport to citizens of East Germany. After the reunification, they lost all such facilities as state enterprises were replaced by a capitalistic economy.

If the world has not significantly changed after the collapse of the Berlin Wall, at least Europe has been transformed with free connectivity, and minimum travel and trade restrictions. The Franco-German and German-Polish borders, hard to cross freely during the Cold War, are now a thing of the past as every year millions of people cross these borders without passing through security checkposts and stringent visa controls. Even the sneaking in of more than one million migrants in Europe in the autumn and winter of 2015 has not led to the transformation of soft borders to hard ones. Populists and right-wing political parties and groups in Germany and other EU countries demanded the imposition of strict border controls in order to prevent further influx of migrants but, despite their demand, the EU borders are generally open.

The fall of the Berlin Wall emerges as a source of inspiration for those who are living under severe restrictions that deprive them of basic freedom. The unification of Jammu and Kashmir has been a long-standing demand of the beleaguered people of that unfortunate territory partitioned since August 1947. But the disappearance of the LoC that separates the people of Jammu and Kashmir and the connectivity of people from both sides is yet to be seen. Like the Germans, Kashmiris living on both sides of the LoC must decide their future and tear down the wall. After decades of suffering, they deserve a better future.

The writer is former Meritorious Professor of International Relations and Dean Faculty of Social Sciences, University of Karachi.

Advertisement