Fiction flourishes in contradiction: Pak author Mira Sethi

"Young people get their news - and their aspirations - from social media and television. Their desires are secular, but the frameworks into which these people are born are traditionalist."

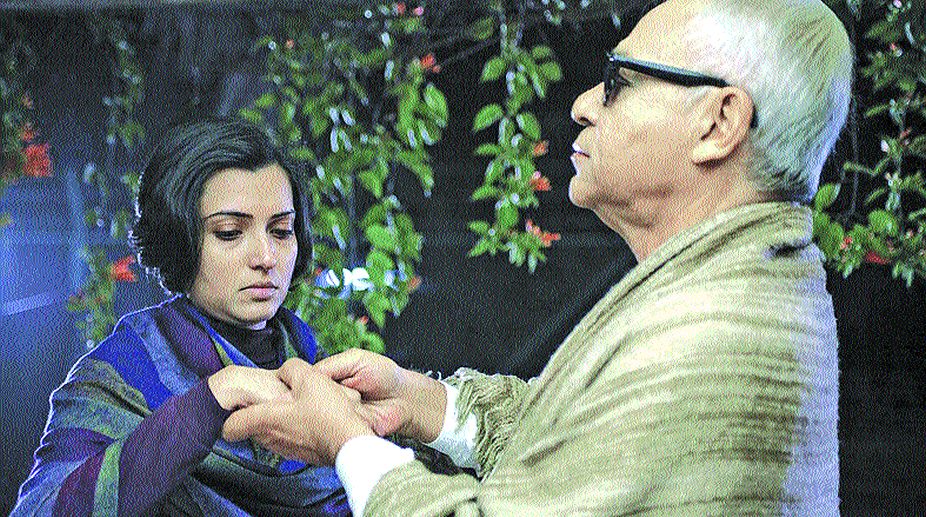

A still from Chitrokar (Photo: SNS)

It required a good deal of courage on the part of Saibal Mitra to attempt a variation on the life and times of the Santiniketan legend Binode Behari Mukherjee without generating a debate on two fronts.

The first area of concern related to the personality of the painter himself. Ashramites and products of Kala Bhavan must be living with countless stories of the muralist who lived almost till the age of 50 with an impaired vision and then turned completely blind in his later years. The film, Chitrokar, concentrates on the personality of a painter who looks much like Binode Behari Mukherjee and is moulded in a manner that makes the connection unmistakable. The screenplay was free to take liberties but any kind of distortion or exaggeration in the treatment was bound to cause a stir.

The other point of concern was the comparisons that could be drawn with the documentary made by Satyajit Ray on his teacher with whom he had spent his years in Kala Bhavan. The Inner Eye was a documentary that had left a powerful impression more than four decades ago. It had concentrated in large measure on the natural sensibilities and unique craftsmanship that had resulted in some amazing murals. The feature film has been made from a different perspective.

Advertisement

The personality of the artist, a fictional character derived from the original, has acquired additional features to which the director has added his impression of the social environment that has changed beyond recognition since the time the documentary was made.

Hence the bridge between fiction and reality raises doubts about whether the film’s protagonist can indeed be considered a variation on the original character. The director avoids some of the questions by changing the name of the character to suit his objectives while exploring the commercial pressures that determine the success of art in a market-driven society.

This was not the dilemma that had confronted the painter who had worked in Kala Bhavan and had acquired his artistic consciousness from Nandalal Bose. Ray’s film was an exploration of the natural gifts that had resulted in amazing work that survives to this day. The film deals with an artist, also based in Santiniketan which provides the backdrop for a drama that has its roots in the city, who is driven into a complex world of commercialised art. It reveals the shades of a personality that is committed to the integrity of his work but cannot reject the forces of change altogether.

The drama consists essentially of the tensions between the blind painter and his young student, a girl from the city who comes to Santiniketan with her own impressions of success. The teacher cannot adjust to the new culture but, at the same time, cannot ignore the realities that his student brings with her.

The film is rooted in this tension and is stretched to a running time that is well over two hours. The director makes a calculated and a somewhat agonising effort to establish the mood and to drive home the point. This may well have been trimmed to a reasonable length without disturbing the fundamental spirit. This is more so because the narrative is virtually drowned in the visual details. Seldom has Santiniketan been depicted with such care and sensitivity and is a major attraction.

It is also woven into the overall statement. Has the artistic environment that was created with profound objectives been gradually defiled by the invasion of a corporate culture? The film touches the broader issues but is more interested in the personality that comes alive with its strengths and weaknesses.

This couldn’t have been achieved with the conviction that is palpable but for the superb performance by Dhritiman Chatterjee. It is perhaps coincidental that the appearance of the protagonist matches that of the real-life character but it adds an interesting dimension to the film as a whole. The interweaving of fact and fiction allows the actor to reveal his personal insights and reactions. It gives the character the sharpness and credibility that constitute the film’s biggest asset.

Arpita Chatterjee also gets into the mood of the young student who represents the new age of art in the market. Some of the situations have been prolonged but, at the same time, it called for remarkable discipline and honesty in the treatment to create a milieu that is so pleasingly different.

The basic idea of an artist who has discovered an inner light is strikingly established in the early scene when he can identify the moment of the rising sun. There are other situations that have been created with telling effect.

All this makes Chitrokar a brave attempt to create an extraordinary character fighting the demons within himself and the battles in a changing world. The visuals support the sensitive treatment and the director sustains the complexities without any kind of concession to popular taste that would have disturbed the spirit of the film as a whole. It is understandable that the film has travelled to several festivals but the question is whether this kind of artistic integrity can find space beyond selective audiences.

Nevertheless, the attempt confirms the director’s uncompromising commitments and offers an unusually rewarding experience.

Advertisement