Iranian President Ebrahim Raisi’s helicopter makes ‘hard landing’: State media

According to the Iranian state media, rescuers are yet to reach the accident site due to bad weather.

When we read about how the country was ravaged by communal violence, we rarely consider the possibility of the British India government’s cold calculations behind it.

SNS

On 15 August 1947, amidst the ecstasy of freedom, deaths of millions in communal riots were forgotten. Our leaders were too busy with the power game to worry about the displaced people in the refugee camps. But we should seriously introspect how a sordid drama had led to such horror, and how our leaders played into the hands of our former colonial ruler. It is true that Jinnah’s obsession with Pakistan demand was the principal factor leading to the Partition. He himself said in 1948, “If I hadn’t been a fanatic there would never have been Pakistan’’. But, Jinnah was not alone in this game of division. There were others. Some of them encouraged him with a specific plan of retaining their control, and some surrendered to his diabolical scheme to capture political power. Let us start with a few instances of British support to Jinnah’s Pakistan agenda. Jinnah told Sir E.

Mieville, private secretary to Mountbatten, about his post lunch interactions with the King and the Queen of England at Buckingham palace in December 1946. Jinnah said that he found His Majesty pro-Pakistan. On talking to the Queen he found Her Majesty even more pro-Pakistan. When Mieville regretted that their Majesties acted in such an unconstitutional way, Jinnah laughed quite a lot. Mieville wrote about it in his latter to Mountbatten in 1947 [Transfer of Power Vol.10 page 198]. It may be argued that when Mieville himself found it difficult to rely on Jinnah’s statement, there is every reason to doubt the story of Royal support to the Pakistan demand. But if it is so insignificant, why did Mieville write about it in his letter to the Viceroy? Undeniably, Britain had a general inclination towards division. This would be revealed from another episode of 1946.

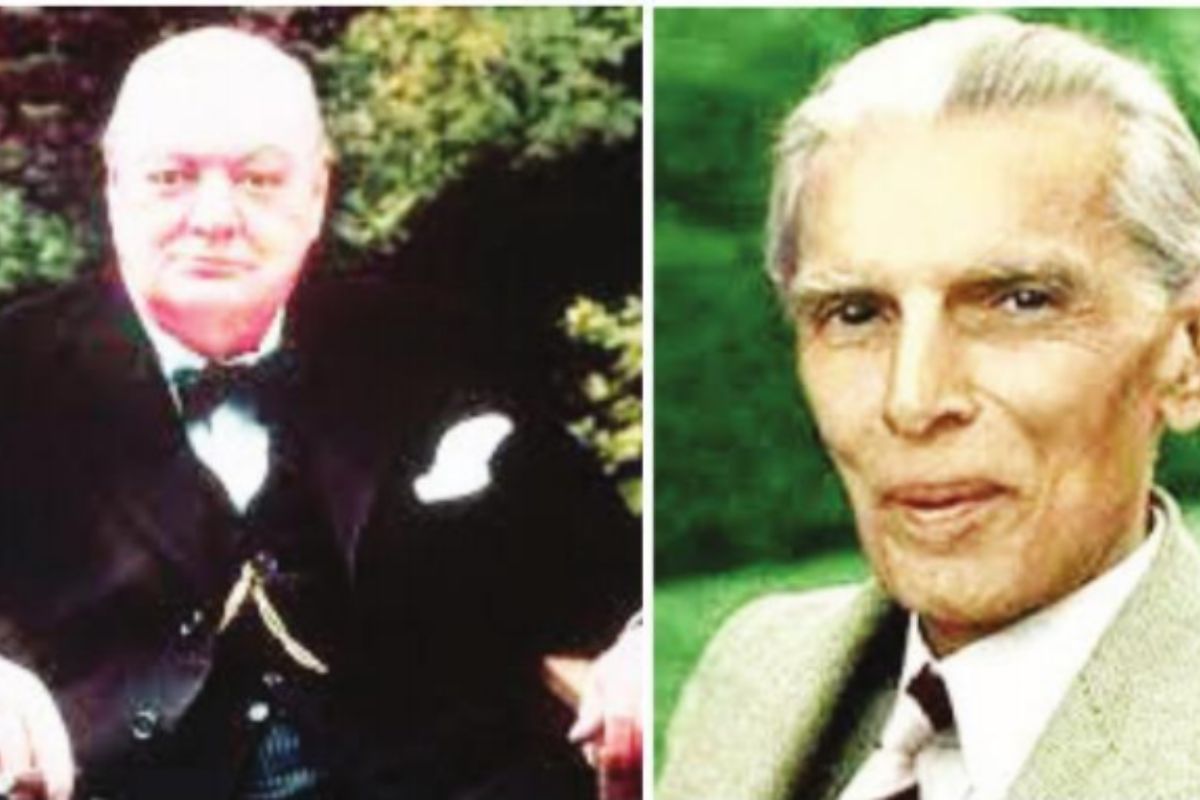

Winston Churchill had always been supportive of Jinnah. There were two reasons for this bonhomie. First, a diehard imperialist as he was, he hated the prospect of Britain losing control of India. Second, he saw in Jinnah’s plan an opportunity for retaining British influence on a weak political entity [read Pakistan] which would be indebted to Britain for its creation. Even when Churchill was no longer the prime Minister of England, he pursued his objectives secretly. ‘The Quaid–eAzam papers’ which Britain collected from Pakistan reveals a shocking document on this secret connection between Churchill and Jinnah. In December 1946, Jinnah went to London on the invitation of Attlee to have a final round of negotiations. He sought Churchill’s advice on this.

Advertisement

Churchill, declining to associate himself with Jinnah, wrote the following letter: “… it would perhaps be wiser for us not to be associated publicly at this juncture…I now enclose the address to which any telegrams you wish to send me can be sent without attracting attention in India. I will always sign myself as ‘Gilliatt’….’’ The address to which Jinnah was asked to communicate was ‘’Miss E.A. Gilliat, 6 Westminster Gardens, London SWI’’. There are more examples of British conspiracy. When we read about how the country was ravaged by communal violence, we rarely consider the possibility of the British India government’s cold calculations behind it.

A secret note of the Director of Intelligence Bureau, Govt. of India, dated 24 January 1947 disclosed, ‘’the game so far has been well played, in that … the Indian problem has been… thrust into its appropriate plane of communalism…Grave communal disorder must not disturb us into action which would reproduce antiBritish agitation.’’ Copies of this note were sent to the British Prime Minister, Clement Attlee and a member of the British Parliament, Sir Stafford Cripps. When in August 1947, communal fury flared up, the British government patiently waited for Indian leaders to concede the transfer of power on Britain’s terms and conditions. This brings us to the role of some other actors behind Partition.

While Nehru accepted the Mountbatten plan of Partition, Gandhiji maintained a double standard on the issue. On 31 May 1947 in his prayer meeting, Gandhiji said, “Even if the whole of India burns, we shall not concede Pakistan…’’ On 2 June 1947, the day before the fateful announcement of Partition when Mountbatten met him, he indicated that it was his day of silence and wrote a note to Mountbatten on five old envelopes: ‘’I know you do not want to break my silence.’’ Finally, in the AICC session held on 14-15 June 1947 it was he who, at a crucial stage, intervened to get the resolution favouring Partition passed. The Indian communists took curious stands. In 1944, CPI [Communist Party of India] leader Gangadhar Adhikari described the Pakistan demand as “the freedom demand of the Muslim League.”

P C Joshi, another prominent leader of CPI, said that as Gandhiji’s slogan of Swaraj gave expression to our freedom, Jinnah’s slogan of Pakistan gave expression to the Muslims’ urge for freedom. CPI changed its stand towards the end of 1945. It proposed 17 Constituent Assemblies based on homelands of “various Indian peoples’’. Such an idea of fragmentation was no less dangerous than the two-nation theory. Britain, fishing in this troubled water, played its end game. What was that game? Let us find out.

(To be concluded)

A version of this story appears in the print edition of the September 7, 2022, issue.

The writer is former Head of the Department of Political Science, Presidency College, Kolkata

Advertisement