The commonly parroted reasons for the failures and persistence of India’s maladies are a lack of accountability, corruption, poor incentive mechanisms and oversized government. Solutions put forth therefore focus on reducing red-tape through technological interventions, bypassing the state, or replacing the government system completely or partially through public-private partnerships.

The suggested solutions do not address the core institutional shortcomings. Most of the remedies are short-term but are neither sustainable nor scalable. The grassroots development staff is required to complete a huge load of paperwork and file many reports to superiors. The system gives so much weightage to documentation that if these duties are not completed and reports sent to the governments regularly, there is no accountability for actual outcomes. Thus paperwork and reporting take precedence over development. Impact assessment is not seriously evaluated, and most findings are manipulated.

Inefficient staff members are often deployed in audits and evaluations because their presence in operations can affect the time schedules of project implementation on account of their inefficiency. Although the development community in India has a vast trove of expertise and wisdom on advancing social change, that knowledge resides in silos, locked in people’s heads or buried within organisations. It seldom reaches the right people, in the right format, or at the right time, for them to act. This limits access to learning, evidence and best practices, constraining what we can achieve.

I have travelled to deeper corners of the development territory to tap surfacing these ideas and insights so that together we can do more and do right by the millions of Indians whom we work with and for. Empowering local governments, non-profits, frontline workers, and supervisors with financial and administrative authority for delivering meaningful outcomes is the most desirable thing to do. Non-profits are criticized often for promising too much and delivering very little.

It is fair to expect them to properly assess their capacities, and accordingly restrict their geographies. Often, it is smarter to do multiple programmes with different departments in the same geography. Further, given the general climate of distrust towards non-profits, it helps if the nonprofit earn the government’s trust and has a work history with it or within that geography before it suggests a new project. In the case of new organisations, the credentials of the promoters will weigh heavily with the government We, self-styled professionals, have enjoyed higher education; we have acquired at least the outward trappings of learning ~ usually by some accident of birth or biography.

The tribe of those who have made the grade through sheer hard work and commitment is shrinking. This advantage gives us access to the decision-makers, to those who decide how the cake will be shared. In other words, we have joined the elite, and the elite enjoys privilege unrelated to merit. It may be wise to remind ourselves of Theodore W. Schultz’s advice in his Nobel Prize Lecture: “Most of the people in the world are poor, so if we knew the economics of being poor, we would know much of the economics that matters. Most of the world’s poor people earn their living from agriculture, so if we knew the economics of agriculture, we would know much of the economics of being poor.

Rich people find it hard to understand the behaviour of poor people. Economists are no exception, for they too find it difficult to comprehend the preferences and scarcity constraints that determine the choices that poor people make. We all know that most of the world’s people are poor, that they earn a pittance for their labour, that half and more of their meagre income is spent on food, that they reside predominantly in low-income countries and that most of them are earning their livelihood in agriculture.

What many economists fail to understand is that poor people are no less concerned about improving their lot and that of their children than rich people are.” ( The Economics of Being Poor ~ 8 December 1979). Rights must be nimble enough to express social concerns and this can happen only when they are realised as policies. Unfortunately, the role of social policy in dealing with disparities has been undermined by creating more and more rights to solve all kinds of problems.

A poor-quality school satisfies the “right to education “; a suffocating 75 square foot dwelling satisfies the “right to housing “; a poor clinic satisfies the” right to health”. We are making a farce of these rights through poor quality and poor performance delivery. What are the ends of development? To grow what is called GDP, or to enhance people’s capabilities, and widen their choices and freedom?

It is now being increasingly recognised that growth is rather weakly correlated with indicators of broader social inclusion, such as employment and inequality. Human well-being is a measure of eight basic needs: food, housing, drinking water, energy, sanitation, education, healthcare, and social security. These needs are embodied in the various rights provided in several national and world charters. It is fundamental to ground these rights into constitutional values. But these can propel change only when they are translated into social policy.

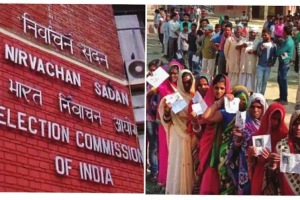

Most times policy prescriptions are often based on ideological leanings. In many cases, articulation of policy directions is also not enough. It is necessary to get into the policymaking process, convince those in senior positions of the need for change and build sufficient momentum for change. The current drive is to shift the approach from assembling plans and budgets in the rarefied atmosphere of bureaucratic corridors to the creation of a mass movement for development in which every Indian recognises her role and experiences tangible benefits.

The new policy strategies are using instruments that affirm their rootedness in ground realities rather than economic abstractions. There is a wonderful articulation of inclusive growth – what we need is growth that falls like rain on the mountains and flows down in streams to the valleys and plains below, not growth that is like snow that sticks to the mountaintops. Inadequate investment in locally-led initiatives is how we fail to ensure that those who are most affected by inequity have pathways to address it. If users do not value the benefits, they will not use the facilities. Local users have much better skills than engineers in adapting technologies to their situations.

The best university-taught skills may not necessarily provide the best solutions. The way forward is to create sustainable, locally driven programmes. For the marginalised to have equal and just access to development and governance, different sectors of society need to deliberate together. Democratic discussion and planning can be creative and impactful and deliver justice. In a democracy, engagement with the government becomes an important part of the struggle for equality and justice.

The recognition of continued engagement as advocacy and the alternate use of action and reflection eventually makes the inclusion of governance a critical issue of concern for alternate strategies for people to influence the instrument of change in their favour. Development is fuller when put in people’s hands, especially the poor, who know best how to use the scarce and precious resources for their upliftment. The first-generation leaders of independent India believed that economic justice would be advanced by the lessons of cooperation where common efforts to achieve the common good would subsume all artificial differences.

We know what the real issues are and we also have the tools for addressing them. What we lack is the will to embrace these solutions, because they threaten some of our self-serving privileges. It’s a delicate issue to initiate change in a traditional culture; it has to be done with utmost care and respect. Transparency is critical. Failures must be acknowledged. Local leadership must be involved in the entire process. There are complex socio-political relationships that must be mediated through the calculus of class, caste, gender and religion.

Fortunately, the academic community is now no longer dominated by the elite. The social background of this tribe is now more representative of the population. The academic work is hands-on and mind-on rather than hands-off, solving real problems and at the same time learning and understanding better how the world works. The traditional dichotomy between the starry-eyed researcher on the high perches who is too busy to reflect, and the practical and culturally rooted development manager is crumbling. Good academics know how to be practical and good policymakers know when they need to move out of their comfort zone and soil their hands.

Major economic transformations typically produce profound social change. With the digital revolution now in full swing, humanity must recommit to building more ethical machines, or face a future in which our technologies undermine basic values like human rights and civil liberties.

The world is being battered by technological disruption, as innovations such as big data analytics, artificial intelligence (AI), robotics, the Internet of Things, blockchain, 3D printing, and virtual reality change how societies and economies work. Individually, each of these technologies has the potential to transform established products, services, and associated support networks.

Taken together, they will upend old business models and institutions, heralding a new era of economic, social, and political history. How will we respond? During the first Industrial Revolution, in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, new manufacturing processes eventually led to huge improvements in human wellbeing. But, early in the process, mechanisation brought negative consequences, like unemployment, child labour, and environmental degradation.

The social and political impact of the digital revolution could be even more dramatic. Wars and revolutions may erupt, and values like human rights and civil liberties could be undermined.

(The writer is an economist, author, researcher and development professional who has spent four decades in the sector. He can be reached at moinqazi123@gmail.com)