Alia Bhatt’s Gucci billboard lights up Madrid!

Alia Bhatt's latest Gucci billboard in Madrid sparks global admiration, while her philanthropic efforts continue to inspire.

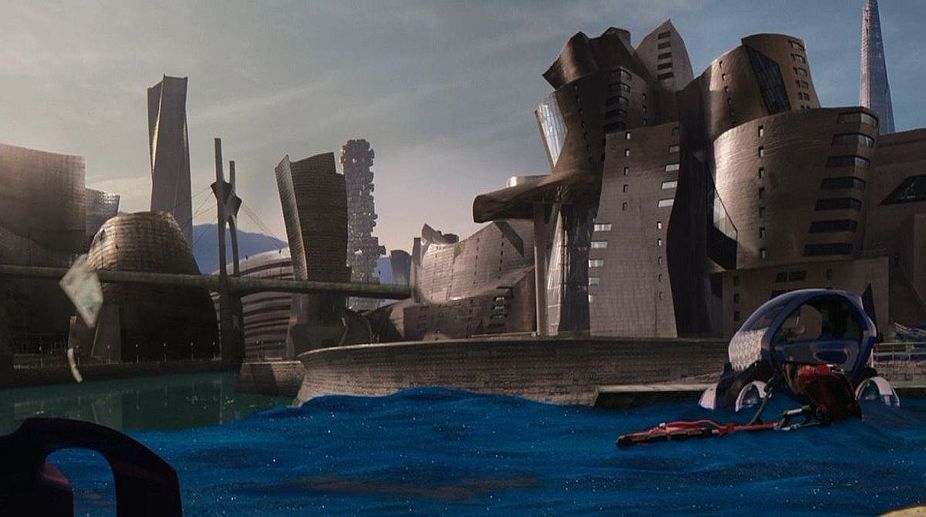

Bilbao Effect (PHOTO: TWITTER)

Bilbao in Spain is the kind of place described in guidebooks as a “working city”. Go back three decades, and few tourists came to this salty port — except, perhaps, those taking a coffee before proceeding on their way to its quainter resort neighbour in the Basque country, San Sebastian.

But this year the fireworks are coming out for a special anniversary. It’s 20 years since the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao was built and the Frank Gehry building, with its astonishing tumble of intersecting titanium panels, introduced the now-commonplace idea that a set-piece cultural icon could play a central part in the regeneration of a city — still something of a novelty at the time. In doing so, it ushered in whole new tier of art-urbanist professionals and gave rise to the dread word “icon”.

“It was a harsh time in 1991,” recalls Juan Ignacio Vidarte, the long-term director of the Guggenheim Bilbao. “There was 21 per cent unemployment. Worst, the city itself had an identity crisis.” The Basque separatist group ETA was active, adding a threatening hint to a city that was already in a bit of a postindustrial hole. A feasibility study was undertaken in 1991; an auspicious area of the Nervion riverside identified, the architect Frank Gehry contracted, and the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao opened in October 1997.

Advertisement

This set in train a series of events that has been dubbed the “Bilbao Effect”, a coinage claimed by writer and broadcaster Jonathan Meades. As well as adding the icon, the Guggenheim also charted the change in museums from dutiful storehouses to zones of visitor experience (as Vidarte says, “They have become hybrid spaces and social hubs), which had almost magical palliative effects. “The Guggenheim has been a tool of social transformation, and a good example of the transformational aspects of culture,” adds Vidarte. “And the effect has been greater than expected, as we underestimated the effect of globalisation — how the Museum would become a world-famous image.”

Thus, in town halls and meeting rooms, a generation of burghers have learned to trade chatter about “metrics” and “cultural capital”, a phrase popularised by 20th-century French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu; as well as take cues from US geographer Richard Florida, who popularised the argument that “creative cities” become rich cities, adding a soupcon of sociological science to the mix. And yet, an anti-icon mood is now emerging. In his new book The Age of Spectacle: Adventures in Architecture and the 21st Century City critic Tom Dyckhoff takes a sceptical view of some aspects of the Bilbao Effect. “The culture of spectacle and what Gehry has called ‘iconicity’ has been such an enormous feature of the last 20 years,” he says. “But particularly in the UK it has sometimes lacked inclusiveness, and made us into passive voyeurs.” At worst, he argues, the gallery icon becomes a “stick-on” that might as well just exist for Instagram snaps. It’s always been a poor fit with our reactive planning system. And also, the money just isn’t there any longer.

There’s also a sense that policy is shifting from “icon” building to a more integrated, grass-roots approach, which develops the arts in a bottom-up community-based way. The Great Place Scheme, funded by the Heritage Lottery Fund and Arts Council England, is giving £20 million to drive cultural regeneration in 16 areas across England (followed by Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland), to a targeted group of moreor-less deprived places including Great Yarmouth, Rotherham and Coventry, now bidding for UK City of Culture 2021. Rather than pushing for icons, it’ll be encouraging these places to use culture and heritage to drive growth, improve residents’ health and wellbeing, and boost tourism, with the arts to be integrated into education and health services. It’s far from regeneration-by-starchitect and close to the concerns of a younger generation of architects who, according to Dyckhoff, are manifesting “a great interest in street-level urbanism”.

Even with the big icons, the model has been criticised. As low-cost airlines mobilised the tourism model of the “city break” the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao alone hosts about 1.2 million visitors a year. “The Guggenheim was always meant to be an international institution based in Bilbao, so the city could speak to the world,” says Vidarte. That may have worked, but elsewhere there’s been conflict about the depredations of “hipster tourism” and disquiet about posticon gentrification, which has led to critical noise about what academic Martin Zebracki has characterised, with a touch of irony, as the “public artopia”.Why have an icon if local artists can’t afford studio space? A recent report by the Arts and Humanities Research Council called Understanding the Value of Arts and Culture is as critical as it is erudite, “The regeneration of places is usually accompanied by gentrification … and the exclusion of communities who live there (as they) are forced out by rising property prices.” Nor are the outcomes always so ensured. Glasgow has a higher global profile as an artistic city, but is still known for a relatively high crime rate and notoriously low life expectancy rate.

Back in Bilbao, however,Vidarte cannot see many downsides. The original arts icon remains solid, assured of its place in history, and still looks great. “Unbelievably the titanium hasn’t even been cleaned,” says Vidarte. But it’s symbolic purpose has lost some of its shine.

The Independent

Advertisement