Quintessentially Bangali?

Bangaliyana is a light-hearted journey to grasp a culture forever infused with nostalgia and nestled close to the heart.

Rousseau writes in The Social Contract, “The social pact, far from destroying natural equality, substitutes, on the contrary, a moral and lawful equality for whatever physical inequality that nature may have imposed on mankind; so that however unequal in strength and intelligence, men become equal by covenant and by right.”

(Photo:SNS)

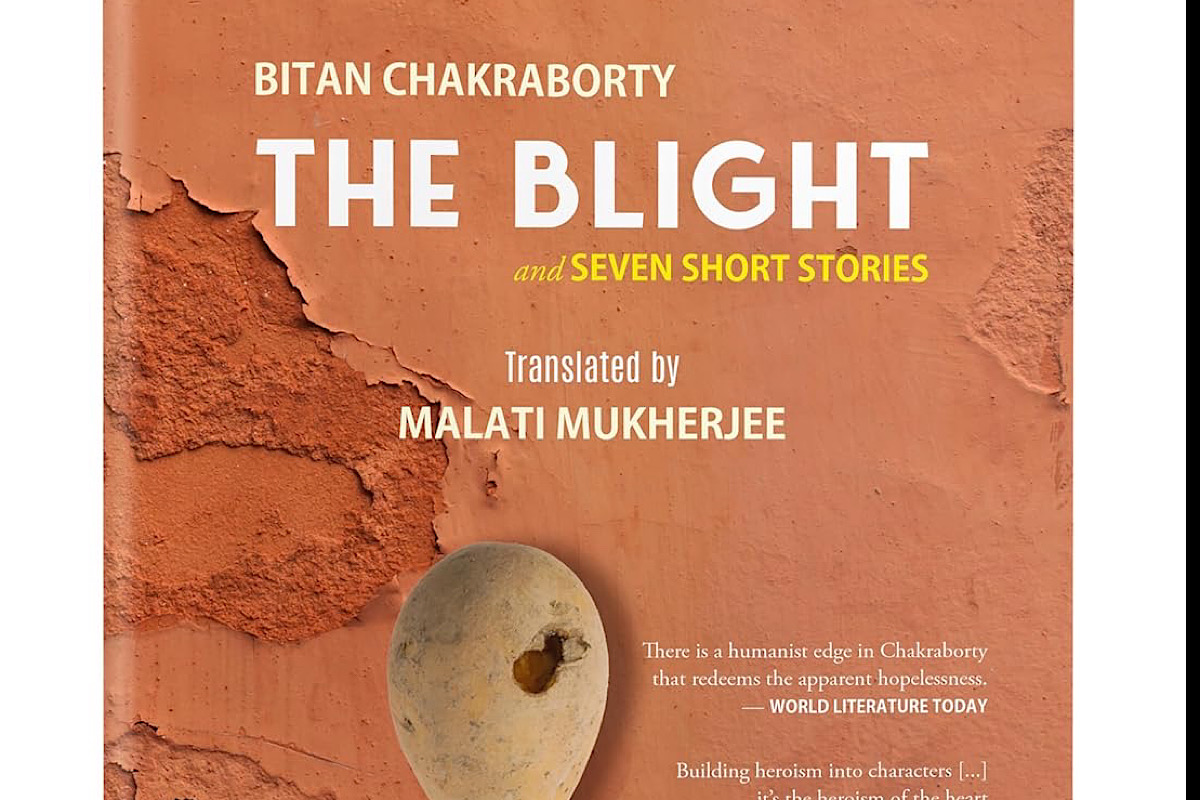

Rousseau writes in The Social Contract, “The social pact, far from destroying natural equality, substitutes, on the contrary, a moral and lawful equality for whatever physical inequality that nature may have imposed on mankind; so that however unequal in strength and intelligence, men become equal by covenant and by right.” This principle was established in the Declaration of Independence and the founding of the United States government. The government exists to establish free competition among equals. In his story “The Blight,” Bitan Chakraborty establishes this truth with grace, realising a socialist perspective. The earth bears the wounds inflicted by human greed multiplied by thuggish privatisation. The story illumines the theory of social contract provided by Rousseau. His characterizations are riveting, timeless, and melancholy. The ending is frighteningly poignant. This kind of emotional realism is also an allegorical warning. As human-based climate change looms, stories such as “The Blight” remind us that we are one with the earth, and her wounds are ours. This ecological wisdom is found throughout Chakraborty’s most recent collection, The Blight and Seven Short Stories.

Chakraborty is known worldwide for his portrayals of average working-class people. Each of these stories carefully elaborates on life difficulties faced in a troubled environment. In “The Site,” we begin with Nalinaksh. He is introduced abruptly, and his story is brief, consisting only of a few pages. In his story, oddly, we learn that his hard work has been detrimental to him. “Resting did not allow you to ride the sky. Not even to hold on to what you had achieved,” writes the author from the character’s perspective. A beggar sits under the Devil Tree across the street, where Nalinaksh jumps from a balcony, committing suicide. There is an outcry from the beggar as the rain blurs his image of Nalinaksh. After his fall, the beggar searches his clothes for something valuable and kicks him harshly. This reversal of his role from abused to abuser suggests irony in the work ethic of Nalinaksh. Obviously, he has victimised himself by seeking socially valuable accomplishments, but he is made equal to a beggar in the end. Death is the great equaliser.

This story was the most perplexing of the eight collected stories. The telling of it is harrowing, but many details are not thoroughly presented, leaving readers to fill in gaps. In “The Blight,” Chakraborty shares ecologically sound wisdom: “Does everyone have the ability to withstand these wounds inflicted by greed? […] the victims of these wounds stand up again as children of nature; they turn their faces towards the light and laugh and play.” A strong empathy is expressed for the earth through Moni, an older family man whose son is a thuggish bully. His son is profiting from black markets. The generational contrast reverses the common thought that older people are more adapted to a sick environment. The wounds of capitalism are steadily presented through the allegory. “The Blight” concerns potato prices and quality on the surface, but the ignorance of merchandisers is contrasted with the immoral world of the black market. In this way, as readers, we think about what circumstances might bring products to market. The author even suggests, “Cold storages may have been invented to help mankind, but this practice of storing fresh vegetables in the cold and selling them the following season is also meant to extract every ounce of life from those same men.” This statement illuminates the author’s radical perspective on the economy. Technology evolves to suit necessity but is often used in ways contrary to that purpose.

Advertisement

Again, in “The Mask,” roles appear reversed. Powerful and influential people can hold themselves above common decency, even in the arts. Puntu creates masks, and a nearby theatre company requires his services. In the end, Puntu removes his mask to play with his child. His child does not recognise him until he does. The actor Neel is cheating on his soon-to-be wife. Puntu’s mask represents the quality of his facelessness and hidden innocence. Neel’s immodesty is clearly contrasted with this benevolence. These kinds of contrasts reflect power dynamics and the devastating impact of the social order on human character.

In “Reflection,” we learn that not only nature bears a resemblance to us but to our fellow humans, too. The Bengali Ahan enters a train in a specialised compartment. Chaos with the local people of Benares ensues. He attacks a vendor on the train after confusion regarding his place on the train. The milkman is a Bihari, a group he classifies as “bastards” who made their own states hell. Although most on the train are Bengalis, his rage blinds him. His reservation on the train becomes meaningless to him after others have taken over without the reservation. While he attacks the Bihari milkman, he suddenly notices that he is in such a furore that he is clutching his own collar. The lesson is: do unto others. The racially intoned conflict on the train represents a need for empathy and respect in the globalising world, as well as the problems created by class.

The translator Malati Mukherjee writes in the introduction, “We live in times of haste and self-absorption.” This defines the spirit of our age. The character of humankind is defaced by greed and rampant individualism, and the social contract erodes under pressure, thus necessitating a need for revolutionary change. Chakraborty’s marvellous stories present us with a conundrum of lasting importance. In certain ways, such stories aid us in aligning ourselves with more humane goals and social structures. This collection of eight short stories aims to suggest how we can traverse the era with grace. Even if a reader is not sympathetic to the political economy of the author, the stories are brilliant and lead readers to reflect on modern conditions.

How can we learn from the blight on humankind’s hearts? In “Spectacles,” a young man named Siddharth is mentored by Sameer Da to learn the misfortunes of the masses through theatre arts from writers such as Bertolt Brecht. Throughout the story, as we learn at the end, his glasses cause him vision trouble, leading to difficult situations. It turns out the glasses were given to him by mistake by the spectacle company. As the story progresses, Siddharth recognises hypocrisies in his mentor and thinks, “His acting only pretends to be something he is not! All lies!” In this story, one recognises the power of consciousness in action. What one does, one becomes. Is developing our consciousness a way forward? What would such a development involve? The author does not necessarily tell us, but his stories instruct us on recognising the blight we face. These humanistic tales are allegories of class and society. They point at foibles, dissect social engagements, and remind us what is truly valuable.

The reviewer is Founder of Transcendent Zero Press.

Advertisement