Preserved OMR sheets would have helped the court: SSC chairman

Mr Majumdar told news persons that the SSC had in an affidavit, thrice submitted the figures of deserving and undeserving candidates in the court but the court was not happy.

Such news doesn’t even shock us any more. It’s easy to blame the SYSTEM and demand some miraculous solution to this alarming issue. But we too are a part of this destructive ‘system’ as teachers, parents, government officials and policy makers, and also as unconcerned spectators.

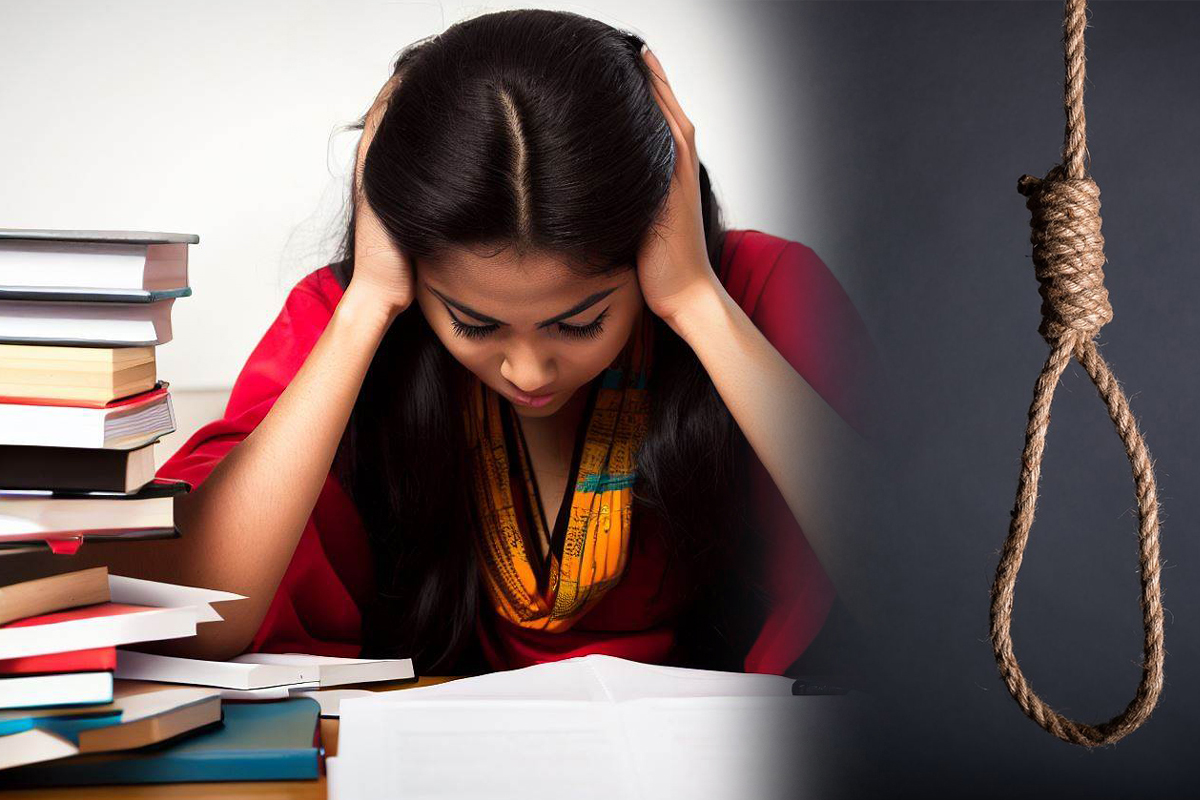

Year after year, stressed students continue to commit suicide in India. In recent days, a 24-year-old M Tech student from IIT Delhi was found hanging in his hostel room. An ITI student fell to death from his hostel roof in Rourkela, Odisha. A 19-year-old student at MAHE University in Karnataka jumped to death from a building after going through the exam question paper. A 16-year-old JEE aspirant hanged himself in Kota, the third case from the coaching hub this year.

West Bengal has its share of student suicides. In November 2023, a 20-year-old NEET aspirant from Birbhum hanged himself in Kota. In June last year, the Calcutta High Court constituted a Special Investigation Team to probe the unnatural death of an IIT Kharagpur student.

Such news doesn’t even shock us any more. It’s easy to blame the SYSTEM and demand some miraculous solution to this alarming issue. But we too are a part of this destructive ‘system’ as teachers, parents, government officials and policy makers, and also as unconcerned spectators.

Advertisement

The young have always successfully overcome pressures and obstacles. Wars, natural disasters, revolutions, and epidemics—young people have triumphed over upheavals through the ages. Very few have committed suicide. They are resilient and have repeatedly taken the lead to improve the world we live in. As responsible members of society, each of us needs to be aware of the threats and treat vulnerable youngsters with sensitivity. We mustn’t allow precious young lives to be destroyed by suicide.

Academic pressure alone doesn’t cause student suicides. Self-destructive tendencies are fuelled by a toxic cocktail of unrealistic parental aspirations, peer pressure to ‘fit in,’ and concerns unrelated to academics. An otherwise balanced youngster, for example, may be already depressed by the death of a parent, financial difficulties, or taunting by peers for being unfashionable and shy.

Complex reasons drive young people to suicide. Parents are behind some of these. It’s important for parents to guide and encourage children to do their best. But ‘tiger’ parents with unrealistic expectations who pressure kids to win every prize, always stand first in class, and outdo the neighbour’s children in every way can only distress a child. Adverse comparisons with others demotivate children. That’s not all. Many Indian parents add to their children’s stress by pushing them to excel in sports and hobby classes. Hobbies are meant to be fun. But these should not be forced on children.

Parents also tend to stifle their children under their own unfulfilled ambitions. A friend now in his forties shared how his father mercilessly beat him as a boy so he would become a high court judge like his uncle. With his inner positivity, he became a competent lawyer, with lifelong regrets because his father was dead against his joining the Army. A weaker-spirited youngster may end his life under such pressure.

The craze for unconventional new-age careers can also cause misery. Only a few can become rich and famous as social media influencers, models, or fashion designers. Youngsters who blunder into such professions may end up paralysed by the fear of failure. Teachers and parents need to impress upon youngsters that behind the perceived glamour of any profession is the foundation of dedication and hard work. There is no shortcut to lifelong success. To help youngsters cope better, parents and elders can build up a healthy understanding with the young, offering them emotional support when they need it.

Peer pressure can pull young people down by making every relationship needlessly competitive. The craze for the latest fashions, phones and gadgets, the compulsion to grab social media attention, party and seek girlfriends or boyfriends, can distract and destabilise youngsters.

Poverty and social isolation appear to have led to the recent suicide of a 17-year-old student at a government ITI in Cuttack. The boy came from a village to a city of strangers. He shared a room with a classmate and worked in a catering service to pay for his studies. As responsible citizens, we should be sensitive towards the struggling youngsters in our midst.

Government policymakers and educational institutions need to ensure our children learn how to adapt and cope. Mental health public awareness campaigns, mental health screenings as part of general health checkups for students, ensuring that educational institutions have trained counsellors, and sensitising teachers are some important steps.

According to experts, suicide is usually a planned decision and not an impulsive act. A suicidal person often shows signs of sudden behaviour changes well beforehand. Alert teachers, parents and friends can watch out for these signs and try to help the suicidal person.

A suicidal person usually shuts out others and withdraws into isolation. Uncharacteristically poor performance and disinterest in studies, uncontrolled anger outbursts, mood swings and talking about death and dying are other early warning signs.

They may suddenly start or increase their use of alcohol and drugs. They may drive recklessly and show other uncharacteristically risky behaviours.

We all need to understand that suicide can be prevented. Trained counsellors and psychologists can intervene most effectively if suspected suicidal people are brought to them early. It is our duty as responsible citizens to be kind and caring to everyone in our social circle. Spending just a little time and attention on vulnerable youngsters around us might make a difference between life and death.

The writer is a senior independent journalist and author based in Bhubaneshwar.

Advertisement