Armageddon Foretold

The most Government spokesmen will concede is that we may experience climate change by the end of the twentyfirst century, to counter which, they have laid down elaborate goals for 2050 or 2070.

It is a worldview that affirms the importance of harmonious coexistence among diverse cultural and religious traditions, fostering an environment of mutual respect and understanding.

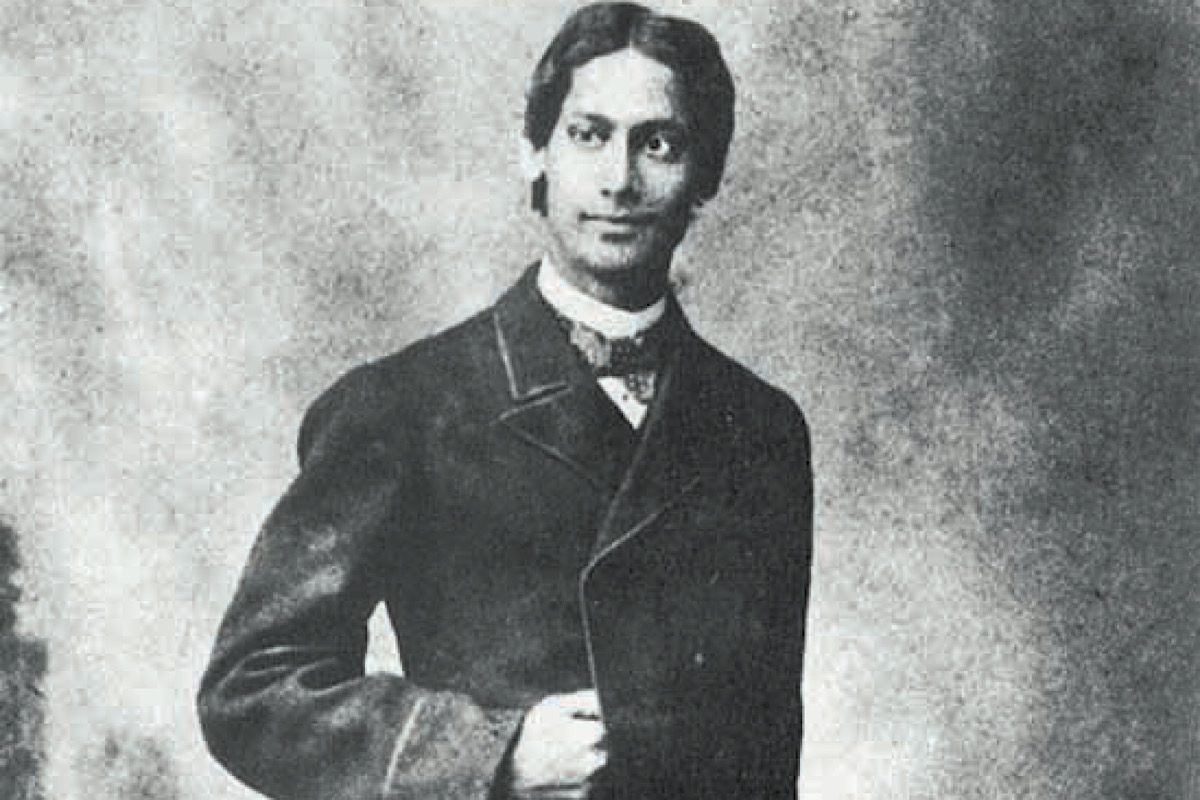

Rabindranath Tagore (photo, SNS)

It is a worldview that affirms the importance of harmonious coexistence among diverse cultural and religious traditions, fostering an environment of mutual respect and understanding. It is a worldview that advocates for the pursuit of truth, purpose, meaning, and fulfilment beyond the rigid boundaries of cultural and religious orthodoxy. At its core, it celebrates a way of life grounded in empathy, benevolence, and compassion, with an unwavering faith in the transformative power of love as the quintessence of the Divine.

Indeed, this is profound spirituality. Call it by any name—transcendental spirituality, universal spirituality, visva dharma, or universal religion—such is the spirituality that Rabindranath Tagore professes and advocates through his writings and lectures. Its universal applicability enables it to resonate with various theological and spiritual traditions, with Christian traditions being no exception.

What is spirituality but the quest for truth, purpose, meaning, fulfilment, enlightenment, love, harmony, and a union with the Divine unfolding within the depths of human consciousness, against the backdrop of an innate recognition of and yearning for the Divine, the source and foundation of all existence? This quest transcends racial, cultural, and religious affiliations, geographical boundaries, conformist institutions, and ritualistic practices.

Advertisement

Tagore’s writings are replete with echoes of such a quest. For instance, in his poem 11 from Gitanjali, the poet-narrator addresses devotees who find themselves obsessed with the demands of organised religions and their institutionalised ritualistic practices and devotions. He urges them to liberate themselves from the confines of their chants, songs, and rituals, prompting them to question whom they truly worship in the secluded corners of dimly lit temples. Tagore’s critique of the formulaic, empty pious practices passed off as spirituality resonated with the ancient Judeo-Christian prophet Isaiah’s critique of similar practices in his time. Assuming the voice of God, Isaiah asks the people. “Is this the kind of fast I have chosen—only a day for people to humble themselves? Is it only for bowing one’s head like a reed and for lying in sackcloth and ashes? Is that what you call a fast, a day acceptable to the Lord?”

The assertions and questions that God places before the devotees through the prophet, “Heaven is my throne, and the earth is my footstool; where is the house you will build for me? Where will my resting place be? Has not my hand made all these things, and so they came into being?” accentuates not only the incomprehensible magnitude of God but also human folly.

It is indeed folly to try to confine the creator of heaven and earth, the transcendent God, within human-made earthly constructs.

Expanding upon this divine declaration, St. Paul unequivocally states, “The Most High does not live in houses made by human hands,” reinforcing the notion that God’s essence surpasses confinement within physical structures. Furthermore, Tagore, in his poem, challenges devotees to transcend traditional notions of worship and embrace a broader understanding of God.

He prompts them to surpass the constraints of sacred spaces and rituals, inviting them into a profound union with God, who could be concerned little with conventional forms of devotion, prayer, and worship. Tagore tells the devotees that God, who transcends conventional spaces, makes Himself immanent in the very fabric of His creation by manifesting Himself amidst the toiling masses as one of their own. This concept resonates with the Christian belief of the incarnate Son of God, who chose to be born and dwell among the labouring masses, intimately experiencing their joys, sorrows, and suffering, ultimately sharing their fate in death for the redemptive cause.

Asserting that deliverance is achieved through the devotees’ immersion in the world, not apart from it, Tagore urges them to seek God through solidarity and service to their toiling fellow human beings. Tagore’s assertion gains greater significance as it draws parallels to Jesus’ teachings, notably the “Parable of the Sheep and the Goats,” wherein Jesus asserts that genuine love for God should be manifested through compassionate assistance to the marginalised and vulnerable.

Grounded in Jesus’s teachings, Christian theology and spirituality maintain that one cannot love God without loving one’s fellow human beings. Yahweh is unequivocal in his denunciation of religious practice devoid of altruistic dimensions. He asks his people in the book of Isaiah, “Is not this the fast that I have chosen? to loose the bands of wickedness, to undo the heavy burdens, and to let the oppressed go free, and that ye break every yoke? Is it not to deal thy bread to the hungry, and that thou bring the poor that are cast out to thy house?” Therefore, love and care for those in need are not merely moral duties but also a means to authenticate one’s true relationship with God. Tagore’s affirmation of this concept in his poem can be considered a parallel insight from Bengal that resonates with Christian theological and spiritual perspectives.

When Tagore says in his essay, “The Realisation of the Infinite,” that “man’s abiding happiness is not in getting anything but in giving himself up to what is greater than himself, to ideas which are larger than his individual life, the idea of his country, of humanity, of God,” he seems to refer to the notion of these boundless possibilities. Tagore’s insight emphasises that true spirituality is found in selfless commitment to principles and causes that surpass individual boundaries, leading to a profound sense of connection, purpose, and ultimate fulfilment. This theme is further echoed in his poem 36 from Gitanjali, where he prays to God for the strength to make his love fruitful in service, never to abandon the poor or yield to oppressive power, to elevate his thoughts above mundane concerns, and to willingly surrender his strength to the Divine will with love.

While the essence of life seems to lie in this profound quest, life should also prepare people for this quest. In his essay, “A Poet’s School,” Tagore argues that “the highest education is that which does not merely give us information but makes our life in harmony with all existence.” This harmony is not just a philosophical concept but a practical approach to life, rooted in recognising the inherent sacredness discernible in every form of life. In his essay, “The Problem of Evil,” Tagore imparts a profound insight: “The most important lesson that man can learn from life is not that there is pain in this world, but that it is possible for him to transmute it into joy, which I believe embodies the essence of spirituality.”

The writer is professor, English department, St Xavier’s College, Kolkata

Advertisement