Security breach at Salman Khan’s Panvel farmhouse, intruders nabbed

Intruders apprehended after a security breach at Salman Khan's Panvel farmhouse. Stay updated on the latest developments.

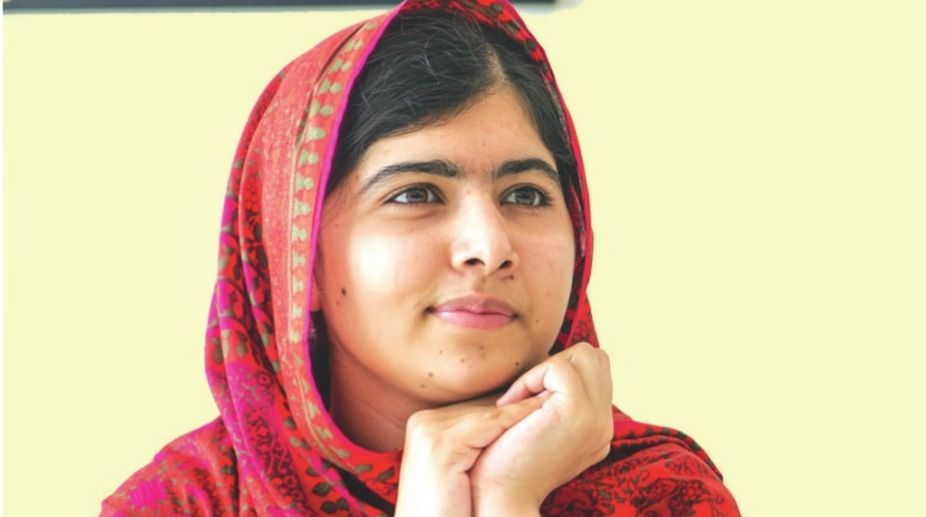

In an interview, Nobel laureate Malala Yousafzai has talked of the girls’ education projects she is supporting in Pakistan but she declined to identify them lest they also face a security threat.

A little over 20, Malala may be everyone’s darling. Wherever she travels from her UK base — from the Middle East, to Africa to Latin America to different European destinations — she is showered with affection and adored.

But at home, at least measured by social media reactions, opinion is split between those who admire her and respect her work to raise awareness for, and give support to, girls’ education and those who seem to have a pathological dislike of her.

Advertisement

Hatred is too strong a word to use but may have been more accurate as what the latter category spews is nothing but venom — from denying that the assassination attempt ever took place, despite the lifelong mark that it has left on her, to calling her a Western agent.

This category of critic has also often lambasted her for using her Malala Fund for supporting girls in other parts of the world but allegedly ignoring her own country. Given how much animosity the young woman can evoke, she is wise beyond her years by not making public the projects she funds and supports in Pakistan.

One can almost visualise every brand of hater from the fanatics who tried to kill her to the ones whose inexplicable anger on social media knows no bounds considering any such project fair game to be targeted, damaged and even destroyed.

A lot has been written about what drives those who unleash attacks on her on social media but having sifted through reams of such material, no clear reason has emerged to me (perhaps a panel of psychiatrists, psychologists/profilers would do better) — unless one attributes this solely to misogyny.

This week I had a depressing conversation with a journalist friend who spent a day in Mardan with Mashal Khan’s family. The family continues to try and come to terms with their loss some seven months after their beloved Mashal Khan was lynched on the local university campus. My friend tells me that Mashal’s father is a learned man, a poet of very modest means who continues to dream of a better Pakistan where innocent people like his son are not falsely accused of blasphemy and killed by mobs.

Frankly, I know of no person who’d be this stoic, even optimistic about the future, after having suffered what he has. Even then, this isn’t half of Mohammad Iqbal Khan’s tragedy. Now his two daughters who were pursuing a pharmacy degree and matriculation cannot go to their institutions.

My journalist friend says this is because of safety fears as they live fairly isolated lives in their community and have to hear daily taunts and threats and are at a loss as to who to trust. They have no means to relocate to someplace safe, far from Mardan.

Policemen guard the family but given the murmuring they have heard, they are unsure of whether they can safely go to their educational institutions such is the hostility created by some people associated with different political parties whose sympathisers have been charged with the lynching.

Doesn’t your heart bleed at their predicament? Forget the government, forget any institutional support. I suspect our top three to four political parties have enough billionaires in their ranks to assist this family, to ensure that the girls can continue their studies elsewhere. They are sharp, intelligent students as their academic record will testify. But will they?

I am filled with doubt, given the attitudes towards women in society. Let me elaborate. A man who read my views in a column on sexual harassment a couple of weeks back and on Twitter after that accused me of saying what I did to “become popular with women or you won’t spread these lies”.

Lies? Well, here is another. By now you may have read thousands of words triggered by a recent ‘controversy’ on whether it is appropriate/ ethical for a doctor to send a Facebook friend request to a patient they have treated/are treating. US, UK and many others have clear-cut guidelines, apparently we don’t.

How to tackle this in the absence of proper guidelines or till they are developed? I was discussing this question with a woman friend who currently lives in the US and this is what she said and has given consent for her words to be used. The purpose isn’t to join one outraged camp or the other. It is simply to understand what happens in Emergency Room (ER) or Casualty or Accident & Emergency.

“I know how vulnerable one is in the ER. In fact, I hadn’t counted before but the incident made me think back. And I’ve been to the ER six times in the last 11 years, three times in Pakistan and three times here, and each time was a miserable experience, usually in the middle of the night, when seeing a regular doctor was not an option and pain was too intense to not do something.

“The first thing ER doctors do is ask your medical history and for women that’s also reproductive and sexual history, how many pregnancies? How many live births? How many miscarriages? How many abortions? Are you on birth control? Can you be pregnant? The whole lot is personal and invasive. If an ER doctor sent me a friend request after that, I would feel incredibly violated.”

The whole idea of sharing this was to offer an insight into how a woman patient might feel. If the reaction such a sentiment triggers is couched in appropriate words or words that are open to misinterpretation it cannot be the subject of endless debate.

What should matter is that awareness should spread far and wide of what is, or should be acceptable and what is not.

Dawn/ANN

Advertisement