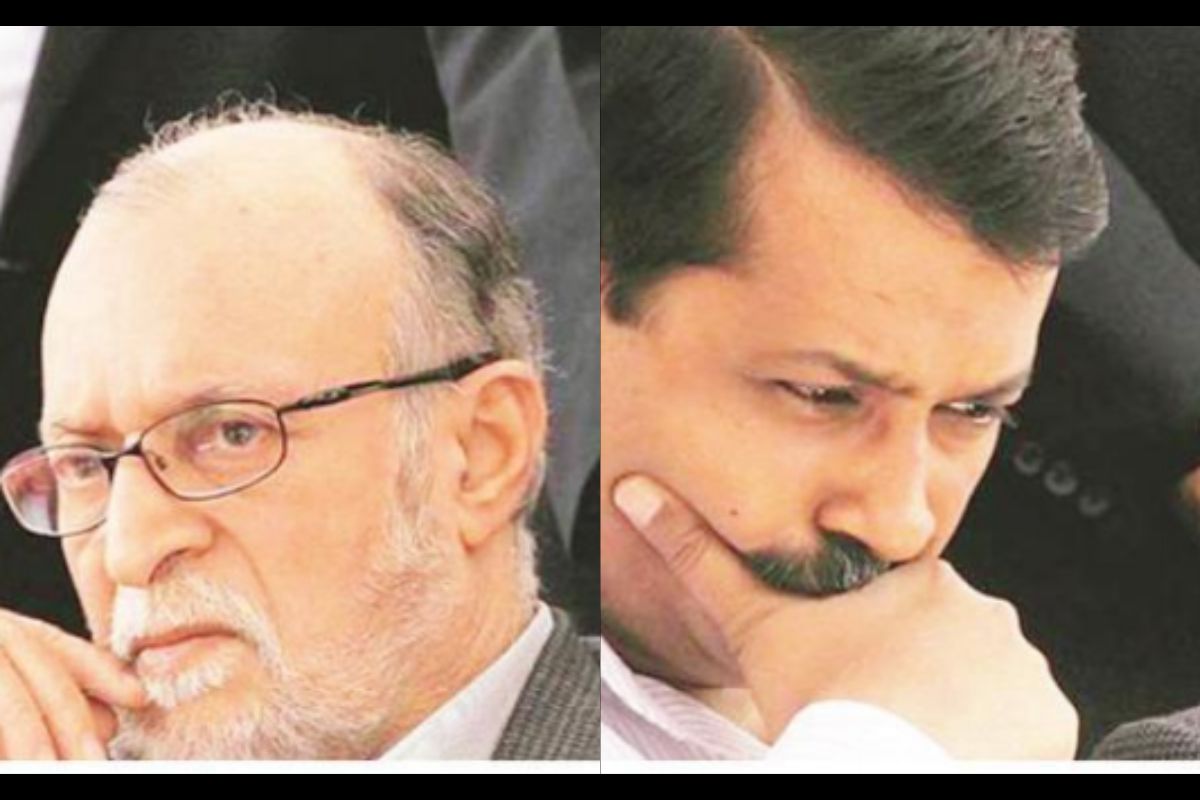

In no way unique or rare, the recent skirmish between the NCT Lt Governor and Chief Minister over the latter’s visit to Singapore is symptomatic of frequent running feuds characteristic of a regime perpetually in confrontation mode not just with Lt Governors, but even with the Prime Minister. The clashes often signify a theatre of the absurd, detrimental to people’s interest. While some say it is the vaulting ambition of an irascible and splenetic AAP supremo that is responsible, it is more a fault of the system. Given the status, trappings, and halo of being chief minister of a state, that too with 67/70 majority in Assembly, it’s natural that the incumbent would hanker for power and influence. Recall how with their avowed unconventional politics, AAP made an astonishing debut, generated a wave of optimism to cleanse the country’s debauched politics.

It lent the party leadership an image larger than life. The systemic fault-line lies in the aura of statehood bestowed on Delhi, which in essence requires a well-functioning mega city municipal entity. Strangely the irrefutable empirical evidence of statehood for the capital city being untenable and impractical is ignored by political masters. Both Congress and BJP have been guilty of promising full statehood for Delhi in their election manifestoes and reversing the stand when in power at the Centre. Ponder the chequered record of Delhi’s governance. Announced at the Coronation Durbar on 12 December 1911 as British India’s new capital, a 1912 notification brought the tehsil of Delhi and the Mehrauli thana to be administered as a separate province under a Chief Commissioner. The Government of Part ‘C’ States Act, 1951 provided for the capital city to be administered by the President through a Chief Commissioner/Lt Governor, with a Legislative Assembly and Council of Ministers, in 1952.

The Legislature had no power to make laws in respect of public order, police, formation and functions of municipal corporation and other local authorities. The States Reorganisation Commission,1953 concluded that the dual control of Delhi resulted in “marked deterioration of administrative standards,” leading to the enactment of the Constitution (Seventh) Amendment Act, 1956, that abolished Delhi’s Legislative Assembly and Council of Ministers, making Delhi a Union Territory under direct administration of the President. As for local autonomy and democratic representation, the Commission suggested a municipal corporation for Delhi (which came into existence on 7 April 1958, in terms of the Delhi Municipal Corporation Act,1957). A rising clamour for ‘popular’ government from power and perks-hungry netas resulted in the Delhi Administration Act, 1966, providing for a Metropolitan Council of 56 elected and five nominated members, with a four-member executive council, one of them designated as Chief Executive Councilor.

The Metropolitan Council had no legislative powers; an overlap of functions and conflict of jurisdiction between the MCD and other agencies rendered them dysfunctional. Then came the S Balakrishnan Committee on Reorganisation of Delhi, which, in its December 1989 report, suggested Delhi to be a Union Territory with a Legislative Assembly and a Council of Ministers. It recommended the MCD to be broken into several municipal corporations, while electricity, water, sewage would be transferred to two new Boards, and fire prevention, health and arterial roads to Delhi Administration, leaving national highways in Delhi and roads in New Delhi to be managed by central government, and all other city roads by respective MCDs.Its recommendations regarding the MCD were not accepted. Parliament passed the Constitution (69th Amendment) Act,1991 and Government of National Capital Territory of Delhi Act,1991, providing for a 70-member directly elected Legislative Assembly and a Council of Ministers.

The NCT Act let most of the executive powers remain with the President, so also powers over services. Implementing the verdict by the Supreme Court in the case of Government of NCT Delhi vs Union of India, 2018, regarding powers and responsibilities of elected government and Lt Governor, Parliament passed the Government of National Capital Territory of Delhi Amendment Act 2021, which came into force on 27 April 2021. Arvind Kejriwal’s obsession with full statehood for NCT dwarfed the space he needed for action. He dismissed former three-term NCT chief minister Sheila Dikshit’s advice that, despite the Union Territory of Delhi’s powers being limited, more than three-fourths of matters of concern to the people can well be addressed within the given jurisdiction. Delhi, like the country’s other metropolises, confronts gargantuan problems. It may boast of a revenue-surplus budget, double-digit economic growth, its GSDP in 2021-22 of Rs 924,000 crore (at current prices), over Rs 4 lakh per capita income (3rd highest, after Goa and Sikkim) vs the national average at one-third of it; yet, Delhi has 675 listed and 82 unlisted jhuggi jhopdi bastis (Union Minister Hardeep S. Puri in Lok Sabha, February 2022).

It has at least 3,50,000 families and over 2 million people living in slums. The Covid-19 pandemic revealed the huge hiatus in healthcare that needs serious attention. So also, huge gaps in demand and supply for quality education and skills development. The mega-scale migration is Delhi’s special woe; the migrants added 45 per cent to city’s population in 2011, up from a share of 40 per cent in 2001, projected to rise to 50 per cent in 2021.One can’t escape incessant traffic snarls, annual inundation, encroachments of streets and pavements, roads overrun by parked vehicles, streets and pavements by squatters, shrines and kiosks. With people pouring into the city and cars pouring on to roads (Delhi has 13.5 million registered vehicles, including 42 per cent ‘invalid’ ones), the outlook for the environment looks grim. Road accidents average 100 fatalities a month. Delhi generates 15 per cent of the country’s solid waste, about 12,350 tonnes a day. Only around three-fourths of it is collected by MCD, 55 per cent of which ends up in three overexploited landfills. With a plethora of elected and other agencies, overload of Delhi’s governance structure has been a huge drag.

In addition to 272 councilors in the erstwhile three Municipalities, 70 MLAs in NCT government and seven MPs, there is the New Delhi Municipal Council for the cloistered Lutyens zone, and Cantonment Board, not to talk of Union government controlling its land and policing. Multiplicity of institutions, often with overlapping jurisdictions and sometimes contradictory goals, make for suboptimal output and outcome, a lot of waste. The two key figures in a civic body are the Mayor and the Commissioner, the Mayor providing requisite political leadership, the Commissioner functioning as executive head like the city managers of American cities, who are professionals and specialists in city management answerable to the elected Council. While a Mayor in an Indian city municipality is seldom empowered, the Commissioner is constrained by different committees with heterogeneous character operating as sub-centres of decision-making without coordination. Local bodies in public perception are cesspools of corruption; councilors and executives in a cosy relationship to share the pie.

As revealed by the Annual Survey of India’s CitySystems 2017 report, public perception endures ~ of cities in dire need of duly empowered municipality as an institution for delivery in areas such as sanitation, health, education, mobility, and housing, matters of real concern for the citizenry. A compact, less di?used, cohesive and cooperative, and much pruned structure will usher in a promising paradigm of urban management, worthy of being replicated across the country. The Central Government needs to help evolve an optimal role model of governance for the nation’s capital, one that is pragmatic and realistic, and conducive to people’s basic civic needs being adequately addressed.

A version of this story appears in the print edition of the September 1, 2022, issue.