India assumes Chair of Asian Disaster Preparedness Centre

India and eight neighbouring countries including Bangladesh, Cambodia, China, Nepal, Pakistan, Philippines, Sri Lanka and Thailand are the founding members of ADPC

Several authors, seers and leaders of freedom movements in India drew inspiration from our own tradition. They sought to build an India that would be rooted in our own social, cultural and political history.

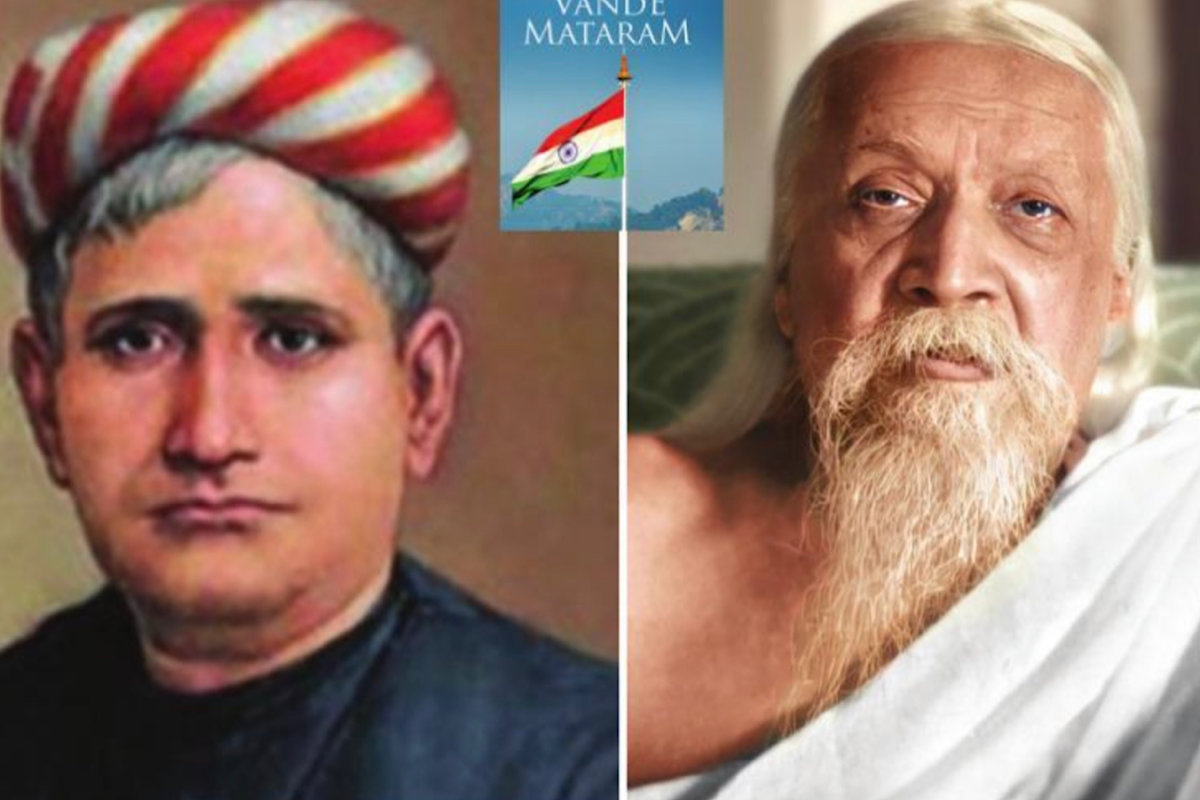

Representation image (Photo:SNS)

Several authors, seers and leaders of freedom movements in India drew inspiration from our own tradition. They sought to build an India that would be rooted in our own social, cultural and political history. People of India, in their heart of hearts, welcomed it as the foundation of our battle against the ruling ideas enforced by the colonial masters.

Let us start with the great author Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay who, despite his keen interest in Western ideas, took resort to a kind of Hindu revivalism in the novel, Ananda Math, especially in the song ‘Bande Mataram’ to promote an anticolonial mind-set. The song and the novel inspired the revolutionaries in Bengal. It raised the nationalist spirit in other parts of the country as well.

The song worships our country as our mother. This was not a religious prayer. Whatever objections have been raised against it, no one would dispute the fact that the song by glorifying our motherland remained the key motivational spirit of all those who fought against colonial domination in India.

Those who find it objectionable that the song and the novel spread Hindu nationalism as the spirit of our anti-colonial battle, should not forget that no less a personality than Sri Aurobindo constructed his nationalist narrative on the basis of it.

At the time of the Partition of Bengal, Aurobindo anonymously wrote a political pamphlet titled ‘Bhawani Mandir’ where he spelt out his idea of the nation. He said that the nation “is not a peace of earth nor a figure of speech”…“It is a mighty Shakti, composed of the Shaktis of all the millions that make up the nation, just as Bhawani Mahisha Mardini sprang up into being from all the millions of gods assembled in one mass of force and welded into unity.”

Advertisement

Thus, to arouse interest in our heritage both Bankim and Aurobindo unhesitatingly took recourse to Hindu symbols. With this they sought to launch a united resistance to the colonial mind-set. The stage was also set elsewhere.

An effort to drive countrymen to focus on Indigenous icons was already under way. It too

helped develop the nationalist spirit in India. Bal Gangadhar Tilak used Ganapati Utsab and Shivaji festival with this purpose in view. This was our India.

There were leaders of freedom movement who never shied away from our tradition of spiritualism. Decolonisation in India grew out of this perception.

Looking back to what we had traditionally, it is evident that our India has always been inextricably bound up with our religious background.

Sometimes, we find efforts to spread hatred toward that religious background condemning it as responsible for the birth of caste divisions in our society.

This view is often held with partisan motives. There are scholars who do not subscribe to this view.

Nevertheless, following the colonial masters’ perspective, our scriptures and certain ancient texts are put in the dock by many for the curse of caste divisions.

It is interesting to note that even the Western scholars did not always pursue the colonial objective of dishonouring India by distorting its past developments. Let us hear from a few such scholars.

The word caste is derived from the Portuguese term ‘Casta’ which means race, lineage and breed. In Indian languages it is often translated to ‘varna’ and ‘jati’. A L Basham in his famous ‘Wonder that was India’ says that ancient Indian literature mentions ‘Varnas’, but it has hardly any reference to ‘Jatis’ as a system of groups within the ‘Varnas’.

Finally, he concludes, “if caste is defined as a system of groups within the class… we have no real evidence of its existence until comparatively later times.” Quite illuminating is the observation of Professor Susan Bayly of the Cambridge University’s Division of Social Anthropology.

She exposed the British Raj’s plan of dividing our society by sponsoring caste. As late as 2001, Bayly said that the caste system, ‘as it existed today’, came into being as a result of developments during the collapse of the Mughal era and the rise of the British Colonial go ernment. The British made rigid caste organisation a central mechanism of their administration in India.

Thus, the statement that caste divisions were inflicted on society in India in the ancient period is too sweeping to be accepted. It is also not acceptable that ancient Indian texts instructed people to develop rigid caste divisions on the basis of birth.

Hindu revivalism was a strong counter to the colonial plan of inciting division since it emphasised the fundamental unity of our society despite its diversities.

Freedom fighters in general and the revolutionaries in particular were influenced by it. So much so that Aurobindo in 1909, in his famous Uttarpara speech, said, “This Hindu nation was born with the Sanatana Dharma, with it it moves [and] with it it grows.” He added that Sanatana Dharma was nationalism.

Those who are out to destroy Sanatana Dharma are better advised to study how it impacted our freedom struggle. It never indulged in any kind of exclusionist attitude. Apart from Joseph Baptista who was closely associated with Lokamanya Tilak and the Home Rule movement, there were non-Hindus like Madame Bhikaji Kama and Ashfaqullah Khan who fought for India’s freedom hand in hand with Hindu leaders.

This India with the pride in its ancient systems and religious background will survive. No force on earth would be able to destroy it. Our India will win its battle against their India.

(The writer is former Head of the Department of Political Science, Presidency College, Kolkata)

Advertisement