India and NATO~III

It can be said that India’s Taiwan policy options are limited. We cannot take on the Chinese single-handedly. QUAD’s policy towards Taiwan is somewhat vague and ambiguous.

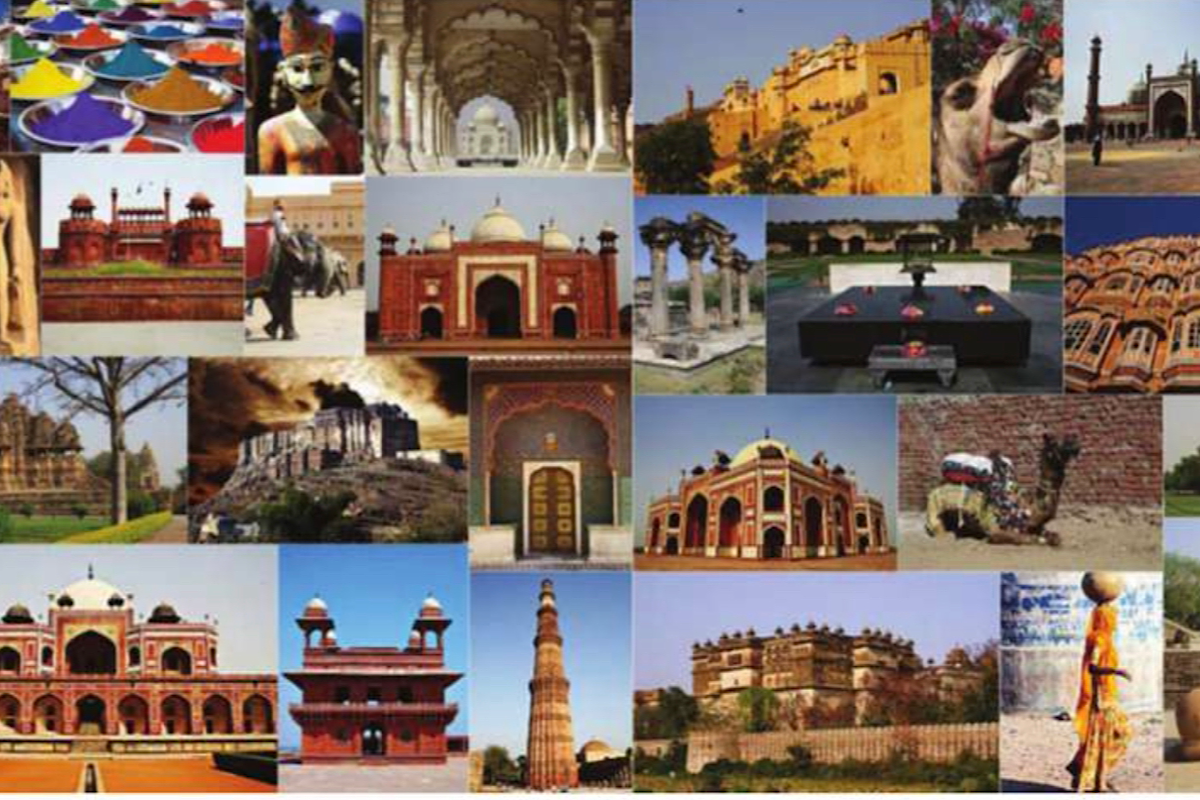

Representation image

Indian cities are rapidly growing into large, diverse and unwieldy urban agglo merations. It is only pertinent to reflect on the plural character of Indian cities, reflected among other dimensions in the country’s rich heritage of city building and in a different manner in the present configuration and condition of Indian cities. One grand plan, an image, or a few landmark projects cannot shape all areas in them well. Therefore, government urban corporations must develop diverse initiatives to improve Indian cities comprehensively.

Indian city-building heritage is worth navigating for its sheer richness and diversity. For example, the art of city building is evident in ancient yet living and vibrant cities like Madurai and Varanasi, steeped in sacral symbolism and a distinct culture. Among other examples, Jaisalmer and Jodhpur’s aesthetically rich historic cities with compact and community-friendly residential neighbourhoods, Fatehpur-Sikri with its splendid poetics of architecture and public space-making or the traditional plan of the historical city of Jaipur with its nuanced variety of public spaces tied to people’s culture, all display a sin- gular strain of masterly city building.

Further, areas developed during the colonial rule in major Indian cities like Mumbai, Kolkata or Delhi, with their vast public spaces and vistas complimented by well-built public buildings of fine architecture, and a modern Chandigarh are also part of Indian city planning and design heritage.

Advertisement

Indian city building heritage is a palimpsest and repository of plural, rich, legitimate planning and design ideas and examples. Modernisation initiatives by the Indian government to improve cities need to be harmonious with the character of this precious heritage. It needs to be conserved with equanimity and studied for lessons to shape present day Indian cities well, closer to the culture of the people living there.Most major Indian cities have areas of different periods, and characters fused within them. From a particular perspective, one can read them as having a congested and decaying older city area, usually of the princely state times and sometimes older, with compact neighbourhoods, bazaars, eateries, affordable merchandise markets and others. In most cases, graceful city areas of the Colonial era succeed with majestic public buildings of fine architecture.

Further, the city areas of the

Socialist phases follow, with their gradually decaying employee colonies,industrial precincts, cinema theatres, and once prominent shopping districts now caught in the cen-

tre of ever-expanding cities. A relatively new energy guzzling and traffic-clogged, opulent tech-glass city of the post-economic liberalisa- tion phase appears later on the urban scene.

It adds to the existing layers of the Indian city, concentrated employment centres and a workforce moving back and forth from near and far-off residential colonies and listless suburbia.

From an abstract stand- point, the informal city of the urban poor and migrant work- ers may be read as being spread in the interstitial unlivable spaces of these varied city areas and on less contested fringe areas of Indian cities.

This mosaic of interconnected city areas and others, each with its internal complexities, also has urban land put to multiple uses. They are also of different ages and characters, sim- ultaneously growing and transforming in time.

Most of these areas, however, fall short of adequate social and physical infrastructure, lung spaces and commons, and public health and sanitation standards. Further, they are lived in by large populations with urban poor, most adversely affected on all counts.

Among other reasons, owing to the prospect of high visibility or ease of implementation or new revenues and employment generation, developing new spectacular projects seems to be

preferred by many State governments over evenly spread city improvement initiatives.

After all, unlike new ven- tures, urban renewal initiatives by urban corporations that attempt to upgrade existing city areas with their ageing infrastructure, multiple stakeholders and intricate issues are invariably plagued by poor visibility and progress.

Consequently, Indian cities witness a systemic loss of verdure natural assets around them due to ever new projects and consequent speculation. Simultaneously, continuous deterioration of existing city areas occurs due to overgrowth and neglect. Further, the sale of publicly owned lands in city areas incessantly by many State governments, reportedly to raise revenues for urban development projects, depletes the prospect of creating lung spaces and commons in existing city areas.

In effect, existing city areas of Indian cities persistently decay, producing unequal urban landscapes. Despite many government efforts, comprehensive improvement and development of all areas in Indian cities seem distant and elusive.

Therefore, while new developments have their role in addressing the needs of ever-increasing urban populations, it is imperative to steer political will with corresponding fiscal investments commensurately across diverse existing areas of Indian cities.

Further, among other measures, urban renewal initiatives need to be incentivized more than other development projects. Additionally, expenditures by urban corporations on pro- jects need to be audited by the authorities concerned for their breadth and spread, not limited to a few items of city improvements or landmark projects.

Also, besides the 74th amendment empowering local municipal bodies and the NITI Aayog committee’s recommendations to strengthen urban planning, the Government of India could develop a dedicated National Urban Services cadre with technical expertise in urban planning, urban design and allied disciplines to lead and support presently ill-equipped urban corporations.

Urban corporations can also institutionalise the participation of corporate and other private agencies, think tanks and research institutions to improve existing city areas.

In addition, while grand master plans for an entire city, among many other functions, regulate the use of overall urban land at a city level, greater emphasis on augmenting them with environmentally and socially responsible ward-wise, need-based local area development plans is essential.

Though National urban renewal missions encourage such plans, their apt realisation by urban corporations true to diverse local area needs remains a mirage. Such area plans need not necessarily target realising a Hong Kong or New York City-like image as symbols of progress or the only development models. Instead, while using urban land efficiently, urban corporations should dovetail them with urban design strategies sensitive to local contexts, informed by lessons from Indian city-building traditions and people’s needs.

Also, recently reported Smart city projects that received awards in cities such as Coimb- atore, Indore, Kolkata, and Thanjavur, under multiple themes not limited to water, mobility, culture, and built environment, can be critically analysed for planning and design lessons.

In addition to these initiatives and select projects, integrated improvement and devel- opment of larger existing city areas holistically across Indian cities is much crucial work wait- ing to be done by State governments and their urban corporations. Such work may have many themes tied up coherently to trigger a larger-scale, effective urban transformation of all areas of Indian cities. In due recognition of the plural charac- ter of Indian cities, governments should look at achieving “good cities for all”, which reads like a new urban mission!

(The writer is a practising architect based in Hyderabad)

Advertisement