Defending India

With challenges on two fronts, India would have to gradually raise its defence spending to deal with increasing external threats

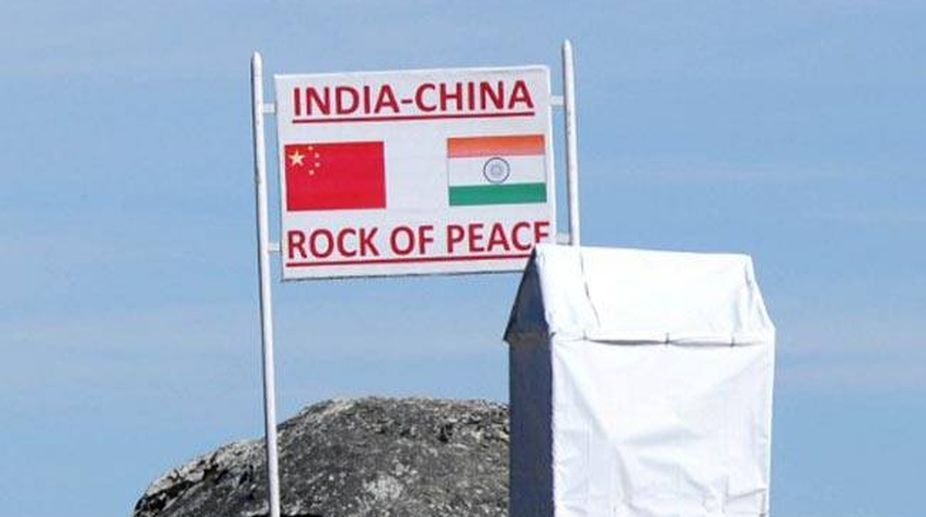

(Photo: Facebook)

In a diplomatic victory, India and China have agreed to “disengage” from the standoff in Doklam on Bhutanese territory. On 28 August, the Ministry of External Affairs announced “expeditious disengagement of border personnel” at Doklam, signalling that the 74-day standoff in the disputed India-ChinaBhutan Trijunction has come to an end.

India has always maintained that it is only through diplomatic channels that such matters can be addressed. Its principled position is that agreements and understandings reached on boundary issues must be scrupulously respected. By the end of the day, as Indian troops withdrew from their post at Doka La, Chinese troops and their road-building equipment too were removed from the face-off site. The standoff has been on since June 15 when Indian troops physically stopped the PLA from building a road on the Doklam plateau.

Trouble erupted when Chinese soldiers began extending a road through Doklam, known as Donglang in China. India deployed troops to stop the construction, prompting Beijing to accuse it of trespass. It warned that the impasse could lead to a wider military confrontation. Its state-controlled media also launched an aggressive PR campaign against India.

Advertisement

Tensions were further inflamed when Indian and Chinese soldiers fought with stones and sticks near the Pangong Lake in the Ladakh sector earlier this month. During the standoff period, Beijing had launched a psychological warfare on the borders of Tibet and Arunchal Pradesh by carrying out exercises with live ammunition just to show off its strength. However, it had no effect on the Indian army. NSA Ajit Doval conducted the negotiations at various levels ~ first, during his visit to China in July, when he held discussions with his counterpart Yang Jiechi.

Next, foreign secretary S Jaishankar led the diplomatic talks with the Chinese side, helped by India’s ambassador to China, Vijay Gokhale, who worked ceaselessly with the Chinese government over the last couple of months to achieve an outcome that would be acceptable to both sides. The army chief and eastern area commander also played a key role in strategically deploying its troops in the war zone. Navy Chief Admiral Sunil Lanba said on 29 August that India’s restraint in the face of China’s belligerent rhetoric worked in the country’s favour, even as the defence establishment did not rule out “pinpricks” from PLA along LAC.

Incidentally, India also provided China with a facesaving exit. China’s initial response on 28 August was to confine itself to saying that only Indian troops had withdrawn from the site, and that they would continue to “maintain sovereignty” on the Doklam plateau. India did not contest this publicly until in the afternoon, when a second Indian statement clarified that both sides had withdrawn “under verification.”

Post-disengagement, China will continue to patrol the region as it had done earlier, but there will be no road construction activity. The resolution comes ahead of Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s visit to China for the BRICS summit in September.

It also comes before a crucial 19th communist party meeting in December when Xi Jinping expects to be “cleared” for another five years and he will choose the core group of leaders who will rule China for the next five years. Top-level sources have also clarified that India had not asked either the US or Russia to intervene on its behalf. While Russia maintained a studied silence, the US made a general statement calling for peaceful negotiations.

It was only Japan, which issued a detailed statement on the Doklam issue, largely accepting the Indian point of view. What is not yet clear is whether this disengagement would lead to boundary negotiations between India and China in the coming months.

There have been no boundary negotiations for some years. Ever since 1962, loyal Bhutan always stood by India’s side. Since India had a festering border dispute, it also kept dragging its border talks with China despite several blandishments including a seat in the UN Security Council.

Nor did it permit China to open an embassy in Bhutan. For a country that aims to overtake the US, this Bhutanese demurral rankles and China did what it knows best ~ it tried to militarily pressurise Bhutan with a road at Doklam.

The Indian Army’s intervention sabotaged China’s game-plan, leading to the standoff and an unending cascade of angry remonstrations. Prime Minister Modi and Chinese President Xi would also have realised that this standoff was diminishing their political capital. Pseudo-nationalists on both sides were on the rise. Their high-pitched economic boycott call forced New Delhi to bend with the wind: anti-dumping duty was slapped on 93 Chinese products and its hot-selling mobile phones are under the intelligence scanner.

Xi is also under attack from his domestic opponents. A reverse on the border would have not only weakened his position at home but would have emboldened the South China Sea rivals to frontally tackle China. The strategic bad blood between India and China will continue. But for the moment, Xi and Modi have patched up with disengagement for peace.

The Indians went in with two demands: (i) China should not change the ground realities unilaterally and (ii) China should respect the 2012 understanding on trijunctions.

This was detailed by external affairs minister Sushma Swaraj in Parliament where she said, “Point 13 of the common understanding states that “the Trijunction boundary points between India, China and third countries will be finalised in consultation with the concerned countries.” Since 2012, we have not held any discussion on the Trijunction with Bhutan.

The Chinese action in the Doklam area is therefore of concern.” During the negotiations, sources said, India held the line that bilateral relations would be affected if China did not ensure “peace and tranquillity” on the border. This could happen only if there was a reversal of the status quo. The two sides only came to an understanding after continued conversations and a realisation in China that India would not move from the ground until they withdrew. Neither side spoke officially on the status of the road whose construction by Chinese troops had triggered the standoff in mid-June, but sources said the area had been “almost cleared” and bulldozers had been sent back.

India had said the road would alter the status quo in the region and have serious security implications. “In the light of the changes of the situation on the ground, China will make necessary adjustment and deployment,” China’s foreign ministry spokesperson Hua Chunying said.

The decision has put a lid on one of the most serious disputes between the nucleararmed neighbours who share a 3,500-km mountain frontier that remains undemarcated in most places. India will have to keep a strict vigil on the border areas of the Trijunction even during winter so that it is not taken by surprise with the PLA’s sudden occupation of the undemarcated areas.

(The writer is a retired professor of International trade. He may be reached at vasu022@gmail.com)

Advertisement