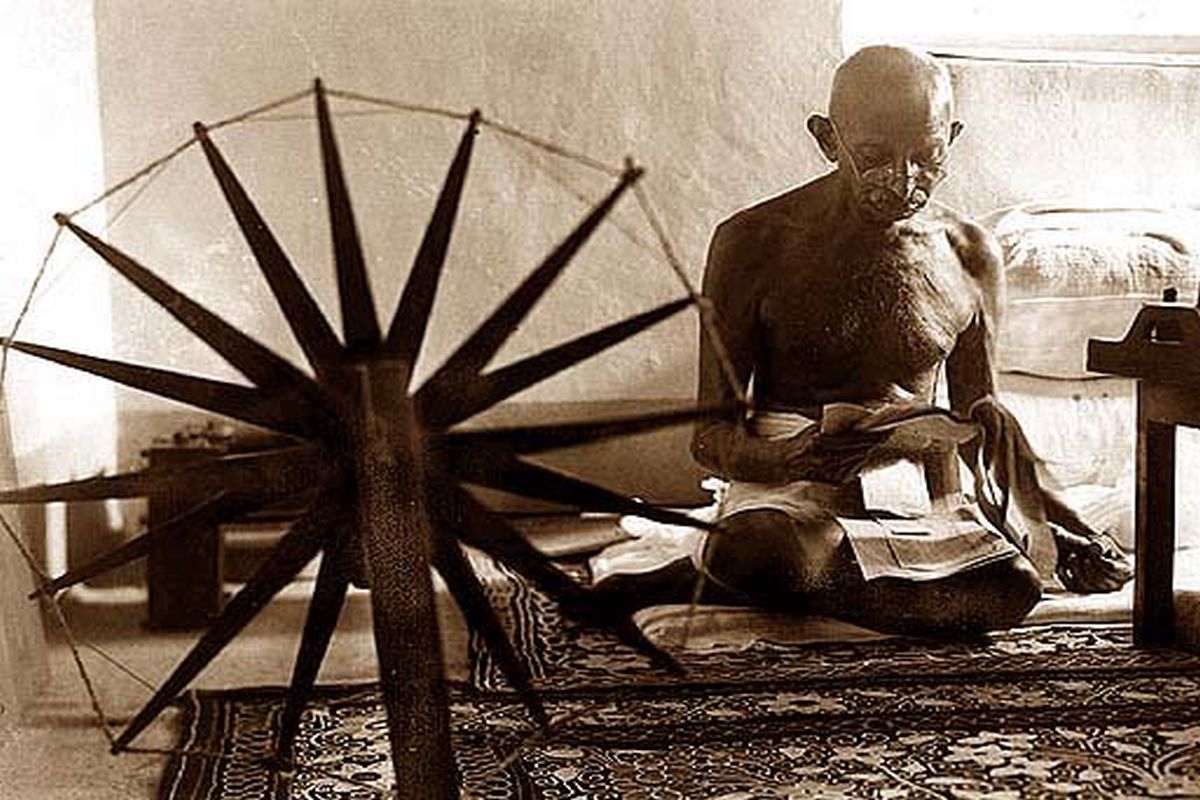

Mahatma Gandhi, fondly referred to as Bapu (Father), was a great life intensively lived at different levels. He had the wisdom of Socrates, the humility of St. Francis, the mass appeal of Lenin and the saintliness of ancient Indian Rishis. A mystic and religious man in personal life, Gandhi was also a great social reformer and one of the greatest political activists the world has ever seen. His experience of the law and colonial administration understandably prejudiced him against considering state institutions as effective vehicles of social betterment. In more contemporary jargon, he was totally against the top down approach. What Gandhi was looking for was not a system but a framework of concepts and values, as well as a method to arrive at them.

In terms of statistics, more than 70 per cent of India’s population live in villages. Gandhi was the ideologue of the village. So in the framework that Gandhi contemplated, the individual is at the centre and the village, and the group of villages encompassing each other in concentric circles. Thus in the structure composed of innumerable villages, there will be ever-widening, never-ascending circles (‘Oceanic Circle’). He named it as Gram Swaraj – every village a republic with legislative, executive and judiciary combined.

Life in villages would not be a pyramid with the apex sustained by the bottom. The individual would rise to the occasion and be prepared to sacrifice everything for the cause of his/ her village. Gandhi emphatically mentioned that ‘Under such a decentralized structure governing rural India, the outermost circumference will not wield power to crush the inner circle, but will give strength to all within and derive its own strength from it. If there ever is to be a republic of every village in India, then I claim verity of my picture in which the last is equal to the first, or in other words, no one is to be the first and none the last’ (Harijan, 28 July 1946). Gandhi used the term Sarvodaya (‘Sarva’ means all and ‘Uday’ means uplift)- ‘the uplift of all’ – for the ideal of his own political philosophy.

When Gandhi returned to India from South Africa in 1915 at the request of Gopal Krishna Gokhale, he found a country that was strange to him. Politics were at a low ebb, chiefly because of the spilt in the Congress; the dominant impulse in India under British rule was that of fear ~ pervasive, oppressing, strangling fear; fear of army, the police, the widespread secret service; fear of the official class; fear of landlords and money lenders. The peasantry was servile and fear-ridden; the industrial workers were no better. The middle classes and the intelligentsia were themselves submerged in the all-pervading gloom. Gandhi realized what kind of destiny was awaiting him. However, Indians welcomed Gandhi, who had upheld the dignity of Indians in South Africa, with open arms as ‘the great hero’.

As per advice of Gokhale, his political mentor, Gandhi had completed the probation period of one year by travelling around the whole country to know India and to gain experience.

Gandhi had the dream of an ideal India and to give effect to that dream of India he chose and joined the foremost democratic organization, the Indian National Congress (INC) instead of trying to build up new institution for the purpose. Even if that became necessary, at times, he tried to set them up by means of resolutions passed by INC so that more and more people could also become involved in it, even if indirectly. Gandhi was acutely aware of the ills of his own society, but his conception of a new society owed much to the knowledge and the reality he gained by traveling around the country. He realised that ‘the soul of India lives in its villages.’ During 200 years of subjugation and exploitation under foreign rules villages had lost everything. Most pathetic was that they lost faith in them. His main task was to rejuvenate villages by empowering them to directly handle the affairs of country’s development and administration. Real Swaraj means acquisition of authority by all.

Indeed, in the two great revolutions in the world the clarion call was power to the people. In Russia, Lenin’s call was power to the Soviets (village communities). In China, being mostly agricultural country, Mao Tse Tung’s call was all power to the peasants’ community. But their ultra-revolutionary talk has distanced the leftists from the daily lives and the needs of the people. On the other hand, Gandhi did not go to the people as a mere peddler of words but with his hands full of facts and materials on a number of useful issues like nutrition, livestock, health, education, equal rights, etc. and in this way he spread the message of ethical life, moral re-awakening, nonviolence and satyagraha and went ahead in organising the people through his Constructive Programme.

His Constructive Programme was the outcome of a well planned and thoughtful agenda. It had been developed by him since 1922 when, after suspension of the Non-cooperation movement, he retired from active politics for about eight years and devoted himself to the organization and implementation of a programme of constructive work. He wrote regularly in Young India and Harijan on constructive works. In 1941, Gandhi first presented his programme for the benefit of the members of the Congress in the form of booklet entitled Constructive Programme: Its Meaning and Place. He revised it in 1945, and in the following year he added one more item to it, namely, ‘improvement of cattle’.

A look at the following eighteen- point constructive programme will reveal how intimately Gandhi wanted the Congress to build up India: (1) communal unity; (2) harijan uplift and removal of untouchability; (3) prohibition; (4) Khadi; (5) village industries; (6) village sanitation; (7) Nai Talim (basic education); (8) adult education; (9) women uplift; (10) education in health and hygiene; (11) provincial language; (12) national language; (13) economy equality; (14) kisan uplift; (15) adivasi uplift; (16) organisation of labour; (17) organisation of students and (18) removal of leprosy.

As to his constructive programme Gandhi said, ’In nonviolence, destruction of the old order is through construction.’ Gandhi kept all these constructive activities free from politics and wanted to lay the foundation of an exploitation-free economy of independent India with the help of such activities. In Gandhi’s reconstruction plan of Indian villages, ‘Every village is a Republic’ whose commune will exercise the power of legislature, executive and judiciary. He said, ‘I am an idealist but claim to be a practical idealist.’ Some may say that Gandhian ideas are nothing but utilitarian ideology written in terms of the Indian social context. But being a votary of ahimsa, Gandhi could not subscribe to the utilitarian slogan of the ‘Greatest good of the greatest number’, rather he advocated the ‘greatest good of all’. To explain the core concept and working procedure of Gram Swaraj it was stated that all decisions therein would be taken on the basis of consensus or on willing consent of all its members. In the absence of consensus, the programme would be kept in abeyance.

To explain the core concept and working procedure of Gram Swaraj, Gandhi said: ‘Your love for your family members should be expanded to embrace village. Then you can the road to goal and all your doubts about man’s capacity will melt away.’ The entire village will then appear as a family. To be precise let us examine acquisitiveness vs altruism. There are two qualities in every man, one is acquisitiveness and the other is altruism. While he is altruistic within his family, outside the family he is acquisitive. While acquisitiveness is the natural propensity of individual, he is none the less altruistic within his family.

On 29 January 1948, the day before his assassination, Gandhi advised the INC in his ‘Last Will and Testament’ to go into voluntary liquidation. As its political objective (to achieve independence) had been attained, it was now time for Congressmen to devote themselves wholly to the education and organization of the masses for Swaraj. But top leaders of party were so enamoured of power that they isolated Gandhi who lamented, ‘I am a spent bullet’. After Independence, Gandhi’s agenda to build a new India was ignored at our peril. Shortly before his death, Jawaharlal Nehru, the first Prime Minister, admitted the predicament that the country faced was rooted in the deviation from the Gandhian path. Indeed, the predicament is the paradox that exists in all spheres of growth and development in India, from poverty to inequality, health, education, jobs, infrastructure, public and private sectors etc. It made Amartya Sen comment- ‘The history of world development offers few other examples, if any, of an economy growing so fast for so long (Indian economy) with such limited results in terms of reducing human deprivation or improving social progress.’

The writer is a retired IAS officer