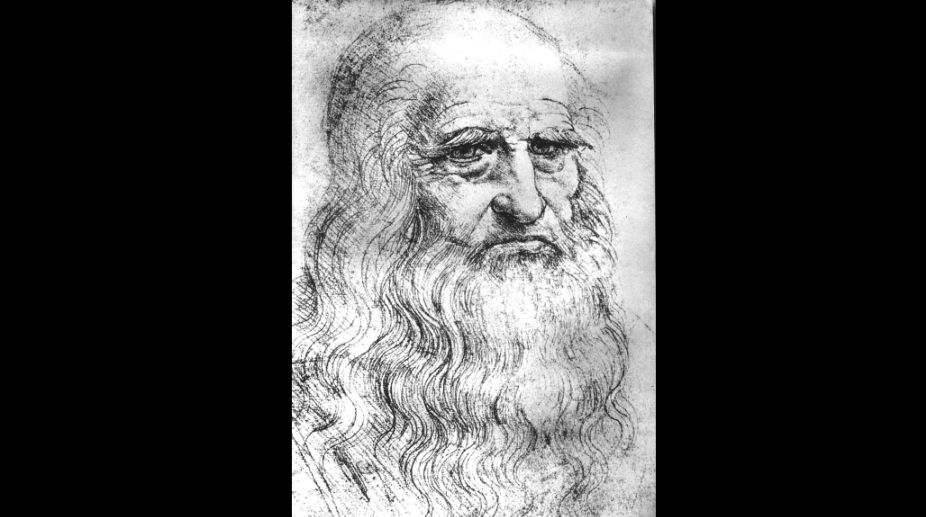

Leonardo Da Vinci: New family tree spans 21 generations, 690 years

Questions potentially probed once Leonardo's DNA has confirmed include reasons behind his genius, information on his parents' geographical origins

In light of the recent brouhaha over Leonardo da Vinci’s Salvator Mundi that was sold for a record S$610.8 million at Christie’s, the interest (re)generated on this artist extraordinaire touches all and sundry across the globe. Contrary to common perception, Leonardo was anything but the ‘perfect’ specimen of humankind. From his birth out of wedlock to his propensity for young good-looking men with “eddies of golden curls” to his short attention span when he would give up an undergoing project without reason, to his heretical attitude for religious authority, the strange combination would have probably been the recipe for abject frustration or disillusionment in another person.

But Leonardo proved to be of sterner stuff, exploding with stupendous talent in the arts as much as in technology, driven to experiments on cadavers and metal structures, his many ventures and forays designing spectacular theatre props or weapons of warfare, even probing the possibility of human flight many centuries before the Wright Brothers proved the theory in reality.

The artistic genius of this painter extraordinaire has been researched with meticulous detail and compiled into a lavishly extensive volume by Walter Isaacson ~ Leonardo Da Vinci ~ The Biography, and comes to us at a pertinent point in time. For any lover of Renaissance art, this is probably one read they cannot forego.

Leonardo was born on 15 April in 1452 to a family of notaries. However, he was an illegitimate child: his mother was a local peasant girl Caterina Lippi and his father Ser Piero. The upside of this was not being sent to a Latin school to be taught the classics and humanities.

Advertisement

Neither completely forsaken by family nor made into an outcast, Leonardo spent his childhood with benign grandparents. The encouraging part was being free to chase his own dreams instead of following his family’s tradition of being a notary.

His only formal learning was at an abacus school. He wrote from right to left and drew each letter facing backward that could be read with a mirror. He also drew from right to left to avoid smudging the lines with his hand.

At the age of 14, Leonardo began working as an apprentice for Andrea del Verrochio at his workshop in Florence. He became absorbed in drapery studies and honed his skills in depicting light and shade to produce three-dimensional volume on two-dimensional surface. He studied the beauty of geometry which he would later perfect when drawing the classic Vitruvian Man.

And it was here too at the studio that Leonardo mastered the ‘sfumato’ or technique of blurring contours and edges. The term is derived from the Italian word for “smoke” or the dissipation and gradual vanishing of smoke into the air. From the eyes of his angel in the ‘Baptism of Christ’ to the smile of the ‘Mona Lisa’, the blurred smoke-veiled edges help the viewer to imagine and roam in a ‘mysterious’ world.

Leonardo made several devotional paintings and sculptures of the Madonna with the infant Jesus at Verrocchio’s studio. His strikingly realistic expressions are proof of his meticulous anatomical observation. His first non religious painting was Ginevra d’Benci and reveals the same magical touch of the master painter in the ‘tiny hint of a smile’ that later found expression in the most recognisable smile in the world.

After working with Verrocchio till 1482, Leonardo went to Florence and thenceforth moved back and forth from there to Milan till 1513. Seven years after his arrival in Milan in 1482, Leonardo got his first painting commission. The portrait – oil on a walnut panel – is of Ludovico’s mistress Cecilia Gallerani, though we know it today as Lady With an Ermine.

Very few will know that Leonardo (then 51) and the legendary Michelangelo (then 28) worked on a common commission, painting a battlefield (Battle of Angbiari) for Florence’s Council Hall. The two were rivals and openly disdainful of each other and also quite opposite in nature.

Leonardo was disinterested in religious practice while Michelangelo was a pious Christian and practiced celibacy. One common trait was that both were gay. Leonardo indulged “in silken robes and fur-lined cloaks”, but “Michelangelo rarely bathed or removed his dog-skin shoes”. Quite a study in contrast.

Da Vinci’s boundless curiosity led him to explore, experiment and experience that would ultimately place him on the pinnacle of artistic expression. His combination of art and technology with imagination was the ideal concoction for infinite creativity. At the same time Leonardo was quite the misfit: illegitimate, gay, vegetarian, left-handed and easily distracted.

Isaacson writes about the process of unravelling the genius, that his focus was not the masterpieces but the numerous notebooks. Leonardo’s mind can best be revealed in the more than 7200 pages of his notes and scribbles that miraculously survive to this day. “Fortunately, Leonardo could not waste paper, so he crammed every inch of his pages with miscellaneous drawings and… jottings that provide intimations of his mental leaps. Scribbled alongside …are math calculations, birds, flying machines, theatre props, eddies of water, blood valves, grotesque heads, angels, siphons, tips for painters, weapons of war…”

It’s a delight to read the artist’s to-do lists: “Get the master of arithmetic to show how to square a triangle”or the random one: “Describe the tongue of woodpecker”. Justifiably, he has been described as “the most relentlessly curious man in history.” Leonardo’s notebooks form the basis of every research and reflect his passionate quest to know the quirkiest facts.

Isaacson discovered that many details on Leonardo’s life, from the site of his birth to the scene at his death are riddled with mythology and mystery. He found that he was “not a giant, he made mistakes”. He left many paintings incomplete, notably the Adoration of the Magi and two others. At present there are only 15 paintings, fully attributable to him, a noticeably minute body of work for an artist of his genius. Even then, his completed body of works finds controversy even today.

Take for example, Leonardo da Vinci’s Salvator Mundi (Saviour of the World). Newly discovered in 2011, it took the art world by storm. It features Christ with an orb topped by a cross. The painting went through many ‘lost’ periods before it was sold in 2005 to a consortium of art dealers and then it went through a cleaning process.

Subsequently, it was sold for almost $80 million to a Swiss art dealer who then resold it to a Russian billionaire for $127 million. Of course, we are all aware of the recent auction at Christie’s where it was sold for a record S$610.8 million.

Leonardo’s The Last Supper depicts the reactions just after Jesus tells his assembled apostles, “One of you will betray me”. It is almost like a moment when time stands still. It was finished in 1498 but in a mere 20 years, the paint began to flake. Over the years at least six major attempts were made to restore the painting. The latest restoration began in 1978 and took 21 years to complete.

But his most brilliant creation is undoubtedly the Mona Lisa, by far one of the most examined and extolled paintings. The portrait is of Lisa del Giocondo, wife of silk merchant Francesco del Giocondo, who commissioned Leonardo to paint a portrait of his wife then turning 24. Yet it was not a mere commission, for it was never delivered. Instead, Leonardo kept it with him in Florence, Milan, Rome and France, 16 years after he began painting it. Over the years he added thin layer after layer of tiny glaze strokes, imbuing it with new depths. He carried it wherever he went, and it was in his studio when he died in Rome.

Mona Lisa’s literally eyes follow you around the room. Dozens of experts have studied it to determine the scientific reasons for this effect. Among them, one is that in the three-dimensional real world, shadows and light on a face shift with distance, but cannot be so in a two-dimensional portrait. That is the reason why we feel that her eyes are string at us, even if we do not stand right in front of it. And most significantly, is her alluring enigmatic “smile”.

Leonardo was fascinated by human anatomy and gave special emphasis on the mechanism of how humans smiled or grimaced. In his notebook accompanying his lifelike sketches, he wrote: “The maximum shortening of the mouth is equal to half its maximum extension, and it is equal to the greatest width of the nostrils of the nose and to the interval between the ducts of the eye.”

He tested on a cadaver how each muscle of the cheek could move the lips, and how the muscle of the lips can also pull the lateral muscles of the wall of the cheek. Imagine, deconstructing the muscular system of the human mouth and lips to create the most famous “smile” in history!

In fact an earlier biographer Georgio Vasari, a sixteenth century artist described it as, “more divine than human.” As Isaacson writes, Vasari even narrated how Leonardo kept the real Lisa smiling during the portrait sessions: “He employed people to play and sing for her, jesters to keep her merry.” Yet the enigma remains. What is she thinking? The smile changes when we move a bit while observing it.

The biography includes all of this and details of sketches and etchings from his notebooks. A beautifully illustrated timeline in the beginning provides a scintillating glimpse of Leonardo’s multi-dimensional life. Indeed, “the fifteenth century of Leonardo and Columbus and Gutenberg was a time of invention, exploration and the spread of knowledge by new technologies…It was a time like our own. That is why we have much to learn from Leonardo.”

Courtesy: Leonardo Da Vinci ~ The Biography by Walter Isaacson, Simon & Schuster

The writer is Features Editor, The Statesman Kolkata

Advertisement