Fire at multi-story building in Delhi’s Connaught Place

Luckily no one is reportedly hurt in the incident as the blaze was brought under control within 2.10 minutes of commencing the fire fighting.

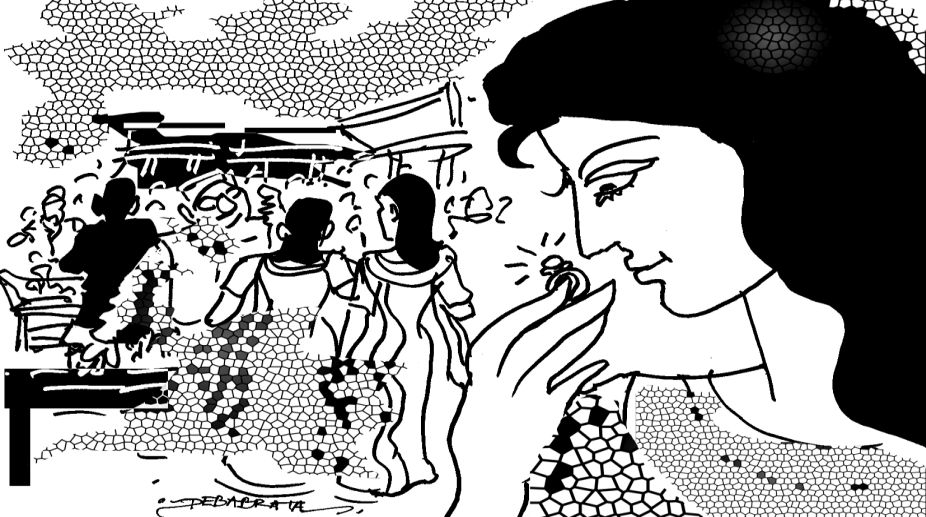

Illustration: Debabrata Chakrabarti

Waiting for Helen di in front of the palatial Connaught Place Khadi, Manashi looked yearningly at Palika bazar but Helen di’s caveat loomed large.“Manu, I shall meet you at CP, but don’t request me to take you to Palika bazar. I don’t do cheap places like Palika.”Yet memories came flooding.

Every time Baba returned from his Delhi tour, Manashi, then in her schooldays, would hover. She never said anything but Baba knew and savoured the moment. He would heave his briefcase on bed and dig in its innards for the bead necklaces, jhumkas and bangles he had bought from Palika. She coveted them since they made her friends envious when she wore them to college.

Fifteen years ago, on her first visit to Delhi, Helen di had given her an extensive tour of Delhi Haat, Lajpat Nagar, Sarojini Market and GK M-Block Market. From Sarojini, Manashi had bought woollens, from Lajpat, suit pieces, from Delhi Haat, tussars, from GK, shoes, chiffons and her first Revlon lipstick. But the jewel in the crown of her Delhi darshan was undoubtedly CP.

Advertisement

Manashi still remembered the sun-kissed morning when she had accompanied Helen di to CP. They had promenaded the circuit, eaten American corn, a delicacy Manashi tasted for the first time, and Manashi had bought Mughal-style miniatures from street-side vendors and brass statuettes of dancing Ganesh, Jagadhhatri and Nataraj from curio shops. Helen di had held her sides laughing.

“Manu, like Bajrangbali you will return with Delhi on your shoulders.” There had been deep satisfaction in Helen di’s laughter. They had a situation on the third day of Manashi’s visit. Helen di had taken Manashi to CR Park fish-market. It was chilly so Manashi had wrapped around her patterned bright blue shawl. Helen di was fashionably attired in black slacks and silver-grey chiffon top. The fishmonger glanced at Manashi and commented, “Your sister from Kolkata, Madam?” Helen di gave him a cool look and tilted her head fractionally.

“We have to do something about your outfits, Manu,” she muttered, “We don’t want fishmongers commenting on them.” Manashi, who had been tickled by the fish-sellers acuteness, knew better than to argue with Helen di, since the latter couldn’t stand tradesmen-camaraderie.

In that one winter Helen di orientated Manashi into the logistics of life-style. With her suitcases bursting with collectables Manashi congratulated herself on acquiring a new and coveted sense of fashion, though it didn’t take her long to slide back to her outmoded, comfortable self once home.

And then globalisation made its lethargic way to Kolkata. Largely it was an odourless, flavourless experience confined to air-conditioned spaces. Never would it match up to the one she had had with Helen di combing the Connaught Circle that sun-kissed morning.

The one place Helen di refused to go was Palikabazar. “It is shady, Manu. And the stuff is mostly smuggled. It is utterly avoidable.” “Who is this snooty Helen di-character? She seems to have dedicated her soul to shopping,” Manashi’s Kolkata friends sneered.

“Helen di is snobbish and arrogant, yes. But she has vast knowledge about interiors, cushion covers, oak panels and photo frames. She is an encyclopedia on skincare, healthcare, food and fashion. She is a history enthusiast. She collects special tickets to view Taj Mahal in moonlight and puts up in a five-star hotel so that she can be up at five to view Taj before sunrise. She and her daughters not only visit mehfils, they make sure they wear Bengal tussars and dhakaimuslins when they do, so everyone knows they are elegant, cultured Bengalis.”

“How do you know the formidable lady?” “Her mother was my pre-school teacher and my mom’s best friend. Helen di’s parents would drink tea every morning from a silver tea-service. She still does. She says a household is not a tea-shop where you simply plonk steaming mugs. In a home you are required to serve tea in a pot with a tea-cosy.”

“Frankly, if you are drinking tea by bucketsful as we do in Kolkata, you will get spondylitis lugging the silver.” “Helen di does it every time. She paints her nails every second day. There are times when her servant plays hooky. Helen di does the dishes, gets her kitchen spanking clean, takes her bath and then sits down with her kit to polish her nails. In summer she wears jootis. Just before winter she gets her pumps and boots sparkled. And she serves fruit only after seasoning it with chat masala and covering the pieces with a doily. “

“Does she have friends?” “One or two. Delhi is not a friendly place and she doesn’t warm up to people. She is more into reading and music.” “Why do you give her such importance?”

Through all the years Manashi hadn’t been able to find the answer to the question. Why did a casual, tea-swigging, chappal-slapping Kolkatan feel so warmly towards a haughty Delhiwali?

But there she was in Connaught Place waiting for her Helen di to come from Alkananda to honour a lunch-date.

When she turned in response to a shoulder-tap, it was to see the smiling face of Helen di slightly emaciated but lean and dapper in peach-chiffon top, black trousers with matching black leather pumps, immaculately done nails and neatly styled page-puffed hair. “Helen di, you look wonderful!” “O, your Helen di has grown old, Manu. But so good to see you! Did I keep you waiting?”

The two entered Khadi. “I buy all my masala from here. The purity levels are high. Nowadays you never know what they put in your spices. You should try the cosmetics too. Wonderful stuff.”

Manashi suspiciously sniffed a bottle. “There is no fragrance.” “Don’t be parochial, Manu. Odour-free cosmetics are the best. That is what I dislike about Bengalis. No instinct for health or hygiene!”

Manashi gave Helen di a hug. It was so good to hear the disdainful, critical stuff after so many years. They began to walk. “Since we are going to cover CP today, I didn’t do my yoga. It is either walking or yoga for me,” said Helen di, “What would you like to have, Manu?”

“What have you planned Helendi?” “Well, there is Biriyani Blues where they serve South Indian non-vegetarian food. It is a favourite of mine, light and flavoursome. Or if you want continental we could go to a place where they serve fresh doughnuts.”

“Biryani suits me fine. But is it healthy?” The last bit slipped out involuntarily. Anyone else would be offended but Helen di was pleased and gave a muted smile. “Of course it is. I am happy to see you are health-conscious, Manu. Look at the way Bengalis are ballooning. No balance or proportion. At least one meal of the day should be vegetarian. But today is special and we will indulge ourselves. Also, South Indian biryani is way lighter than Kolkata biryani.”

The shops fell away on either side as they walked the pavement. “You should have told me you want to do Humayun’s tomb, Manu. It takes more than two hours. You cannot skim through something as vital as that. You need to read a lot of literature and minutely observe every nook. There is Hindu, Islamic and then Jewish influence as well. I mean I do it that way. I don’t know about others,” said Helen di referring to an earlier conversation when Manashi had revealed her desire to visit Humayun’s tomb with her.

“No, no, that is all right. There is always a next time, Helen di. Tell me, how are you?” “I am doing well by the grace of God. Eating right and exercising on a daily basis are the secrets to good health. What do you eat for breakfast?”

Manashi mumbled. The last piece of information she wanted to share with Helen di was she loved parathas and potato-curry for breakfast. The foot-walks of CP segued in a wide arc as the two women, mismatched in attire yet so very pleased to meet for a few hours at least, strolled in a leisurely manner. Manashi slowed in front of a collection of metal figurines neatly arranged in a corner.

“Look at the Vishnu-murti, Helen di.” Helen di peered at the collection. The portly lady in charge volubly praised her wares, but Manashi could feel Helen di had switched off and was minutely sizing up the statues.

“Haanji,” she finally addressed the lady holding up a black figurine, “How much is this little one?” Manashi was disappointed. The large, brassy one had attracted her. Obediently, however, she fished out two five-hundred rupee notes after Helen di had haggled over the price over quarter hour.

“Manu,” confided Helen di in a low voice, “You’ve got yourself a bargain. That is a Kanhaiya-murti, the most graceful among statuettes, and can you guess what it’s made of? No? Gun-metal! Just think the figure of the Black One actually forged out of black metal! What an acquisition! Preserve it Manu, it is a unique piece.”

Manashi stared at Helen di, her fingers involuntarily closing over the little lump the paper-wrapped murti made in her duffle-bag. She gazed beyond and her eyes fell on one of the cave-like entrances to Palika. Helen di followed her gaze. She halted. Manashi stopped with her feeling guilty at being caught staring at forbidden territory. Helen di took a deep breath as if she had finally arrived at a decision.

“You want to visit Palika, right?” Sensing consensus Manashi nodded rapidly. “Come let us go.” Helen di walked through the maze of tunnels tight-lipped, head held high. Brawny salesmen, half-leery, half-solicitous, attempted to guide them into winter-wear shops lined left and right, but Helen di paid no attention. Manashi followed her, downcast by her uptightness. What was the point of entering Palika if they cold-shoudered all shop-owners?

Helen di halted in front of a shabby, ill-lit shop with dull silver plates set up in tired angles against its glass window. She strode in. An aged, fair-complexioned, bespectacled gentleman folded his newspaper and rose to greet her.

“Madam, what a pleasure! We meet after a long time…” “You know bhaisaab, how much I dislike coming to Palika. But my sister here is from Kolkata…” The gentleman smiled knowingly.

“Kolkata,” he murmured, “How are the Chamba Lama sisters? Do you visit them?” Manashi nodded eagerly. “I was there last month,” she said, “You know them?”

“Yes, some of my pieces are bought from them. And the trade is two-way. They buy my items too,” he volunteered. “Rings, we will see rings,” Helen di insisted. Silently, magically, a tray of rings materialised in front of them. Helen di ran a practiced eye over them. “No,” she said, “Another tray, please.” Manashi felt positively wounded. Helen di didn’t even think fit to ask her what she wanted. The bulky silver necklace for example festooned on the wall facing them, or the chain-pendant with the dancing Nataraja. Chunky statement-jewellery was in vogue in Kolkata. Who wanted a ring that would be practically invisible on her thin fingers?

“A cocktail ring…” Manashi tentatively suggested. “…is the ring that gets full-marks for vulgarity. Therefore, no. When you buy a solo item, there has to be an element of singularity. Wait, we have something here.”

When Helen di picked up a delicate silver ring with a solid ruby nestling in a wreath of diamonds, Manashi couldn’t believe her eyes. Helen di firmly took her hand and slipped the ring through her ring-finger. “A perfect fit,” she commented with satisfaction, “the stones are semi-precious, but there is elegance there, don’t you think?”

When the shopkeeper named the price Helen di whispered, “Pay him, Manu. It is a bargain. Now we can have our lunch in peace. My cookery show begins at six. I must be off before that.”

As they came out in the fulgent sun, the ruby twinkled. No glitter, no flash, only a soft, classy twinkle and that too only in the appropriate light. Manashi took a minute to admire the precious ring hugging her ring-finger then happily matched her pace with Helen di.

Advertisement