The Doklam stand-off poses a serious security risk to the whole of South and Southeast Asia. A hurriedly-called meeting in Kathmandu of the foreign ministers of the Bay of Bengal Initiative for Multi-sectoral Technical and Economic Cooperation, last week saw hectic behind-the-scene negotiations to ease the Doklam tension. Prior to that, the meeting between the national security advisors of Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa, held in Beijing, also deliberated on gradual troop withdrawal from both sides.

Even after the brief confrontation in the Pangong Lake area in Tibet, Chinese soldiers and personnel of the Indo-Tibetan Border Police and the Indian Army men exchanged sweets at several points, including Doklam.

The Chinese are trying to make a similar territorial occupation, like Indian Army’s presence in Doklam, to score an equaliser. Both sides are searching for grounds for a just war to be fought in future. But the inner resilience demonstrated by both China and India to the prospect of fighting a useless war holds ground so far.

China and India have many shared roots. Both sides are anguished at each other, but they know that war will only add fuel to fire. China is no alien in India, just as Indians can claim sufficient familiarity in China.

The Chinese news agency, Xinhua made a spoof video with a haggard looking Chinese man pasted with a turban and moustache and posing as an Indian Army officer. He was speaking in a distorted Indian accent to say that India is committing “sins” and bullying the tiny Himalayan nation and whitewashing its illegal acts. Needless to say it was a racist and jingoist portrayal that no civilised nation would do to others. The level of humour carries the sting of India bashing, which is a popular mood in the Chinese media. The Global Times laid out a plan for fixing a deadline that China will announce for India to withdraw from Doklam during the ensuing Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa summit to be held in September in Beijing.

An aggravated rhetorical attack on India in the media seems to be a Chinese method of bullying combined with trespassing the Line of Actual Control, as happened across the Pangong Lake and Chumbi Valley by crossing and flying over Indian territory by Chinese helicopters in July and early August. India did not respond to such provocative bellicosity and maintained calm, while it kept the Army prepared to confront any Chinese incursion into Indian territory in J and K, Sikkim and Arunachal Pradesh.

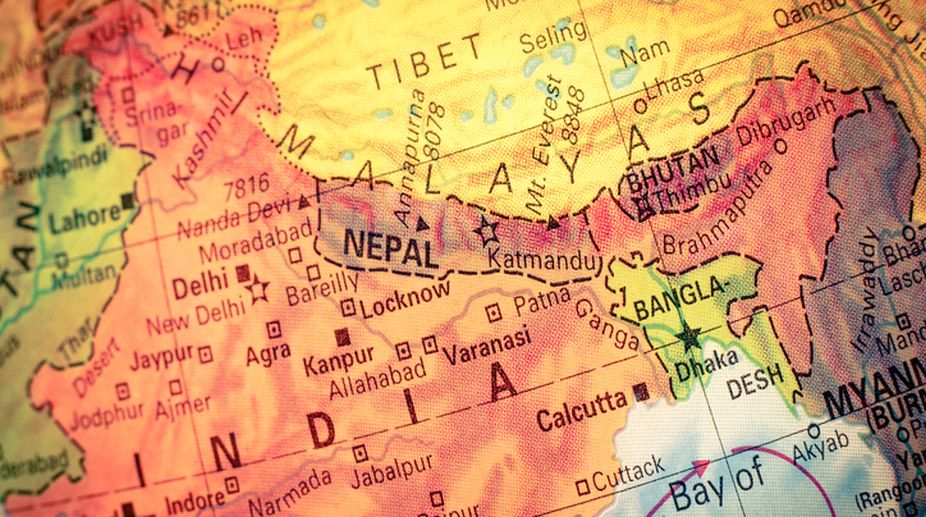

China is visibly rattled and disturbed by India’s opposition to its road building at Doklam Plateau that makes the entire Sikkim and the “Chicken Neck” near Siliguri (connecting the North-east with the mainland) easily accessible to the Chinese army. It is in India’s overwhelming geo-political interest to protect its territorial sovereignty from a possible Chinese aggression in future that India needs to maintain the mutually agreed status quo in the Doklam region.

India just cannot watch as a passive bystander at the Chinese action of endangering the entire North-east by building a road in the Doklam Plateau, at a height of 15,000 ft, from west to east. That makes India’s strategic Siliguri corridor vulnerable to land attacks.

In terms of geo-political calculations that reveal the Chinese plan of road building and setting up an army camp near Jampheri ridge, two km south of Batang La, it is a clear attempt to alter the tri-boundary point between China, Bhutan and India. That would amount to unilaterally enforcing an acceptance of the Chinese position that Mt Gipmochi is the common limiting point that allows descent onto south-western Bhutan and then further downward to the Siliguri corridor. For India and Bhutan, the highest mountain that separates the watershed flowing into respective countries as the principle of drawing up the boundary, is clearly violated by this Chinese insistence on Mt Gipmochi as the border, as the highest mountain is Batang La.

The very debate on determining the boundary and the threat to use its firepower, like arrogantly flying combat helicopters over Chumbi valley and intruding into Indian skies and subsequent refusal to allow a dialogue based on mutual respect and international norms, signal an ominous gameplan. Chinese conditions, that Indian troops move back from Doklam plateau where Chinese road building is supposed to go through, is an attempt to violate the international convention of natural watershed with an intent to threaten India’s territorial sovereignty.

Right now, India has moved its elite strike corps near Sikkim border to counter the Chinese army’s war drills in Tibet. In a sense, the Indian Army is prepared for defending its position. Preparedness is taken to be the only answer to any Chinese threat. Across the Himalayas, the disputed and unsettled boundary in multiple locations, largely between Tibet and adjacent South, Southwest, South-east and East of Tibetan plateau, a large number of watershed and hills are yet to be earmarked.

India’s insistence on certain strategic locations to protect her own sovereignty, in that context, cannot be seen as unilateral imposition of a military boundary. China wants to make diplomatic gains out of India’s continuous quest for unmapped strategic locations at several places near its constituent states adjacent to China’s extreme border points. India’s setting up of the Dhola post, north of the McMahon Line and the policy of surrounding Chinese posts in places like Aksai Chin, have effectively countered Chinese expansion policy to protect their occupation of Tibet since 1950.

India followed a similar geopolitical and strategic policy of resistance of Chinese intent to set up its military installation as close as possible near Indian sites in Himachal, Kashmir, Arunachal, Sikkim and other locations. Indeed the very state sovereignty of India gets diluted by the Chinese strategy of moving forces, ammunition and supply line, which India needs to snap as and when needs arise.

India’s claim on its own territory through a Line of Actual Control has already made China accept India’s legitimacy in areas such as Tawang, Chumbi valley and Bumla pass , as also in the Sikkim-Tibet border point at Mt Gipmochi.

Nevertheless, Doklam valley is an area that falls within Bhutan’s western-most province of Haa and extends up to Gipmochi and beyond. China’s extension of road from Sinchella pass to Doklam shows its military ambition to control the trijunction located across the Doklam valley. This is how in 1987-88, China had a bloody confrontation with India at Nathu-la and Cho-la, some distance from Doklam.

For the North-east the Chinese arms-twisting is an ominous signal, as it brings back the memory of incursion through Tawang, Mechuka, Walong, Jairampur and other such areas in 1962. The Chinese propensity to claim the whole of Arunachal Pradesh and the recent attempts to develop military roads near the Aksai Chin in the form of the China-Pakistan economic corridor from Karkoram to Gilgit, also points to a joint military and economic offensive against India’s national interests.

India responded to such designs by initiating the Trans-Arunachal Road development project that connects Bomdi- la, Tawang, Ziro, Along , Mechuk, and on the eastern side Walong-Kibithoo, Nampong and Miao that can allow faster movement of the Army and logistics.

What is significant here is the steady decline in trust between two powerful Asian neighbours, the spur of which lies in China’s unilateral expansionism and exertion of strategic pressure on India, Bhutan, Myanmar and Nepal. Indeed, China is expanding a shadow-state through Tibet, just as it did in Macau and artificially constructed islands in the South China Sea.

A drift towards warfare between India and China is sure to affect the Chinese economy more than it would affect India, as China’s export and import are both going to be hampered, given India’s strategic superiority over the Bay of Bengal. At the same time geo-politics is never on the side of the North-east and China’s plans of intrusion disturb the peace and stability of an otherwise internally-challenged social and political setting of the region. As a result, India has to make sincere attempts to find a trade-off route to de-escalate military tension in the North-east and other Himalayan zipper points.

The writer teaches Philosophy at North Eastern Hill University, Shillong