Late actor Soumitra Chatterjee doubles up as painter

A few of the works on show seemed more like light-hearted doodling, even puerile, which the actor was not too eager to disclose.

The Statesman gets an insider’s view into an author’s mind.

The year 2023 marked the centenary year of Indian filmmaker Mrinal Sen, undoubtedly Indian cinema’s most consistently polemical filmmaker. To pay a homage in ‘Silhouette’, the magazine I edit, we carried several articles for the four weeks starting with his birthday on 14 May. The articles, critiques and reviews covered different aspects of his cinematic career and urged the reader to probe further to revisit his cinema and to re-examine the political intellect of its auteur. As part of the editorial process, I wanted to ensure that the retrospective of articles covered not only the critical analytical areas of Sen’s work but also reviews of his films, from Neel Akasher Neeche to Ekdin Achanak, just to provide the reader with a glimpse of the artistic sweep that Sen could muster in his films. It will be important to point out that through my writings on cinema for the last quarter of a century, I have tried to tread a path that is neither obscured behind academic jargon befitting academic classrooms nor frivolously anecdotal.

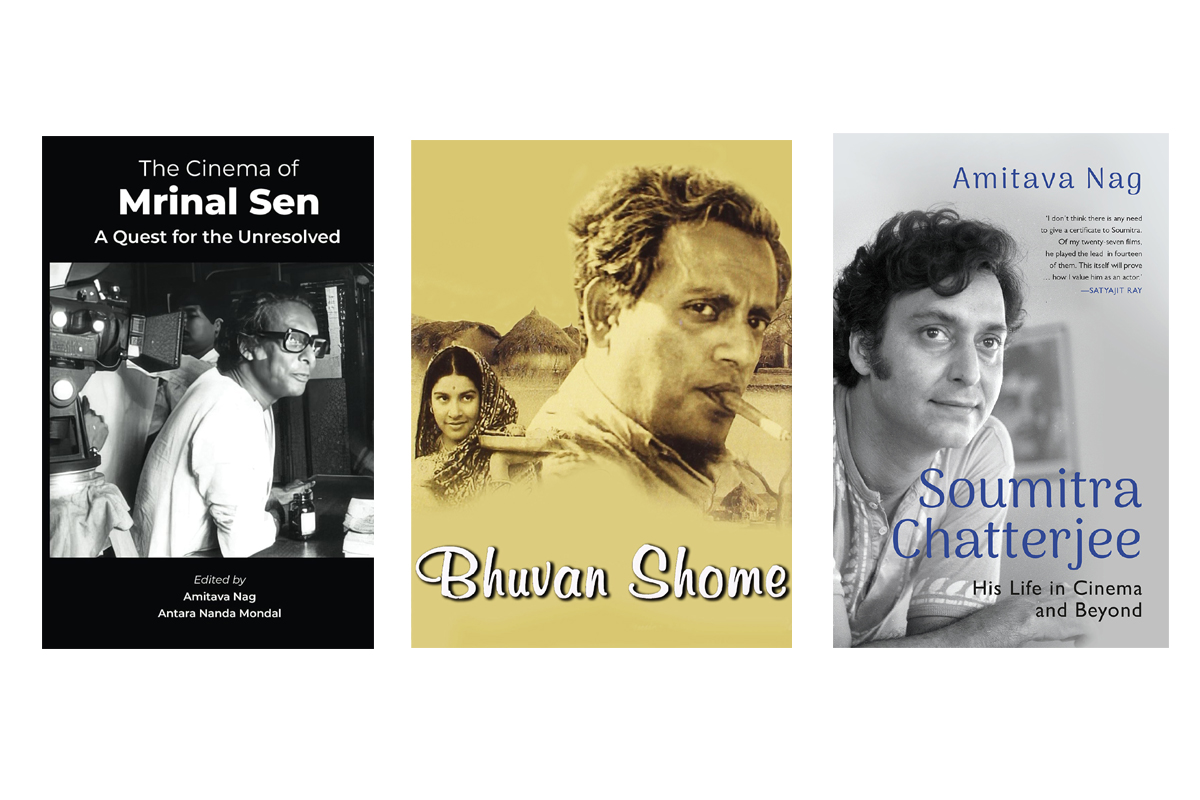

From his contemporary films in the early 1960s to his epoch-making Bhuvan Shome (made in 1969, which ushered in the Indian New Wave), from his angst-ridden films on his El-dorado Calcutta to the more subtle trajectory in the films of the eighties, Sen constantly surged to find new meanings, new ways and new paths to his cinematic truth. His films, apart from a handful, were never popular at the box office, but that didn’t make him cautious about experimenting with ideas and forms. At the same time, he made films in other Indian languages apart from his native Bengali or the oft-accepted Hindi, a feat probably few Indian filmmakers can think of emulating.

For me, the crux of understanding Sen’s militant transformation in the aesthetics of his cinema was a call of the times. It was impossible for a politically aware Sen to find his expression only through farce and satire aimed at the middle-class bourgeois. The lustrum from 1966 to 1970 holds the key to this transformation. Even earlier, through Punascha (1961), Pratinidhi (1964), or Akash Kusum (1965), Sen was trying to understand his time and space. But in 1968, after making a commission for Moving Perspectives and looking at the happenings in his beloved city, Sen felt the desperate need for a change in attitude. For him, the linear narrative mode of filmmaking, with occasional freeze shots and jump cuts, was no longer enough.

Advertisement

The idea of bringing out a series of commemorative collections on the auteurs of Indian cinema had been with me for some time. The Cinema of Mrinal Sen: A Quest for the Unresolved is ‘Silhouette’s first attempt to physicalise such a notion in print. There are quite a few centenary tributes in the form of magazines and anthologies in Bengali for Mrinal Sen this year. I haven’t come across any in English so far, apart from his son’s memoir. I think the book will fit nicely within the oeuvre of writings on Sen’s cinema.

My book, Soumitra Chatterjee: His Life in Cinema and Beyond, is the first creative biography of a man who could be aptly termed Bengal’s last Renaissance man. I had been closely associated with Soumitra Babu (as I have always and will continue to refer to him) for over a decade. I had earlier written, in 2016, Beyond Apu: 20 Favourite Film Roles of Soumitra Chatterjee, where I selected along with him and then discussed his revered film roles. I met him almost on a weekly basis, exchanged phone calls, and spent hours discussing life beyond cinema. In my interactions, I could perceive him as a product of our time and our culture for over half a century. Yet he has known the secret to transcending time and culture in the most magical way since he approached life with openness and generosity.

In our addas, there have been some common themes: separation, return, fear, and death. Then painting, poetry, and reading. He would tell me more than once, “Amitava, I have lived your age. I know how it is. But you don’t know yet how my age looks like. I don’t envy your age.” After he passed away, I could talk to myself in silent breaths, resulting in Murmurs: Silent Steals with Soumitra Chatterjee. It is a personal account, more about my dilemmas with life and art than about him.

When my editor friend, Shantanu Ray Chaudhuri, asked me to write a biography of Soumitra Babu, I was initially hesitant. I finally agreed because, though Soumitra-babu never gave me that duty, deep inside me, I felt I had a responsibility towards him. To project him as a polymath, wearing so many creative hats. As a case in point, in the mid-70s, as he changed his profile (his hair style and his dressing), he was silently moving to his theatrical roots. An intelligent man. Soumitra Babu, deep down, probably understood that roles befitting his talent would stop flowing his way. The likes of Tapan Sinha and Mrinal Sen shifted to other leading men. Even his mentor, Satyajit Ray, cast three different actors for his Calcutta Trilogy. This shift to theatre as an actor-director ensured that he could write roles he would want to play until his stardom was intact.

It is because of this sensible calibration of his career that he never wished to venture out into Hindi cinema, knowing his limitations. It is because of this that he could pace his creative innings in pursuit of excellence in every decade since the ‘60s. Poetry, recitation, and theatre—the trio nursed his creative mind, kept him vibrant, relevant in the ‘present’, and ceaselessly profound.

The writer is an author, film-magazine editor and film critic

Advertisement