One of my favourite things about writing is meeting people and learning about their lives and their place in history. A former journalist of The Statesman pointed me in the direction of Nihar Ranjan Chakraborty’s when I was researching for my book on the 1971 Bangladesh Liberation War.

Chakraborty was a businessman back in 1971. He ran a chemical manufacturing enterprise and lived in a house on Russell Street, which he owned. He was a personal friend of Golak Bihari Majumdar, then the BSF’s inspector general for the Bengal frontier. Majumdar, a former Calcutta police commissioner and later IG-Bengal, called upon Chakraborty’s assistance on at least three different and very significant occasions during the Bangladesh Liberation War, many secrets of which played out in Kolkata.

The first was when two East Pakistan legislators—elected as members of the Pakistan national assembly following its first general election in 1970—came to the border seeking a meeting with the country’s top brass. The Awami League had swept the elections, but General Yahya Khan refused to hand over power to the Bengalis of East Pakistan. Following months of a stalemate, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman proclaimed Bangladesh’s independence and was arrested that night following an assassination attempt.

The BSF received the two Bangladeshi politicians, and Majumdar personally escorted them back to Calcutta. They arrived late at night and were put up at a safe place in the city. The Naxal conflict kept people off the streets of Calcutta, and eateries shut early. Chakraborty’s first assignment was to provide dinner past midnight for the two VIP guests. He managed to drum up a feast for them.

The two Bangladeshi guests were Amirul Islam, who was active in forming the first and exiled government of Bangla Desh (as it was known till Liberation), and Tajuddin Ahmed, who later became the prime minister of the exiled Bangla Desh government.

Chakraborty’s second assignment was to organise meeting places for Majumdar and Hossain Ali, deputy high commissioners of East Pakistan. The two met at Bercos and also at Blue Fox, whose owner was Chakraborty’s friend. The meetings led to the deputy high commission defecting, with its staff and building across Park Circus Maidan defecting to Bangla Desh, a day after the exiled government and its war cabinet were sworn in.

Chakraborty’s third task was to gather around 50 unmarked cars that could ferry local, national, and foreign correspondents to the venue of the swearing-in ceremony. It helped that he was a civilian so that he would not set off foreign spies who hung around Calcutta those days, finding ways to destabilise any moves to help Bangladesh secure its freedom.

It wasn’t easy to get hold of more than 50 cars with drivers who would not be told their destination till the last minute. Chakraborty leaned on his friends and associates in the business community and pulled it off. The journalists were told on the night of 16 April that they should be at the Calcutta Press Club before dawn the next day. The cavalcade of cars left with the reporters and officials for Baidyanathtala, which is in Bangladesh and is now called Mujibnagar. These events are described in detail in my book, India’s Secret War, published by Penguin Random House India in June 2023.

I met Chakraborty for the first time in 2022 to interview him about Golak Bihari Majumdar, and he not only verified many facts, but I could also get detailed descriptions of what Calcutta was like at the time. Through our sessions, I was amazed with Chakraborty’s lucidity and recall of dates, times, names and faces, despite his age. It led me to question his diet and exercise regime over the years, while both of us were digging into sweets at the time.

Last month, I visited Chakraborty again, and he told me that he completed 100 years last December. We celebrated his birthday with Rosogolla and anecdotes about his life, which began as a student volunteer with the Anushilan Samiti.

Following independence, Chakraborty launched his own businesses. He also organised one of Calcutta’s first art exhibitions on a grand scale along with a few friends.

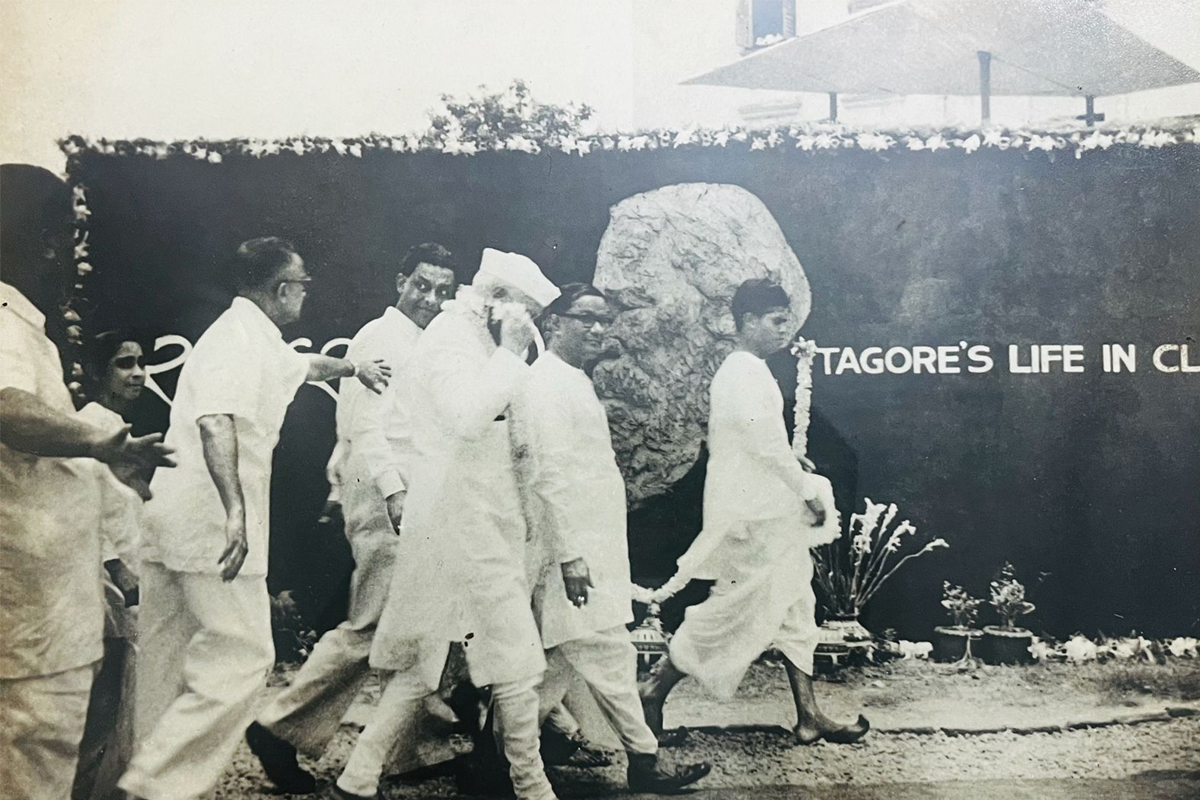

It was a tribute to Tagore on his birth centenary, and they had a good lineup of artists but needed a heavyweight to launch the fair. Jawaharlal Nehru was headed to West Bengal to attend some programmes to observe Tagore’s birth centenary. Would the prime minister inaugurate the art fair too?

Chakraborty reached out to Bidhan Chandra Roy, West Bengal’s chief minister, who helped him secure the prime minister’s attendance after some trouble. Chakraborty seems to have maintained steady influence and connections in at least four chief ministers’ offices.

Nehru nearly didn’t make it; his convoy was held up by protests at the Shyambazar crossing and a stray shoe flung at the cavalcade. Nevertheless, the prime minister made it to the art fair and inaugurated it.

Chakraborty’s interest in art and artists from Bengal spanned most of his life. He collected a lot of it for himself, too. Sometime back, though, he decided that he would pass on his treasures, but he was neither married nor had any children. He gave away his humble persona collection to the Ramakrishna Mission and now lives in South Kolkata.

26 March, the day Bangladesh declared its independence, came and went without any celebrations this year in Kolkata. The people of this city had made contributions, both large and small, back during the nine-month-long struggle. It should be celebrated here every year.

Ushinor Majumdar is an award-winning investigative reporter and author of India’s Secret War and God of Sin.