Blackpink’s Lisa announces own management label ‘LLOUD’

Lisa took to her Instagram to announce the news about her new label 'LLOUD' along with a new profile photo.

After World War II ended, many such third world countries sprouted. But there was and is until today no book to guide them to rise. Lee had to dream and discuss with a few colleagues to convert the ideas into a reality.

It was the best teacher who usually became the school principal and the best professor the head of a college. In hospitals, the best doctor was made the dean. It was as though these institutions did not need specialised management. In the bargain, the best teacher or doctor got lost in the labyrinths of administration not really knowing what to do.

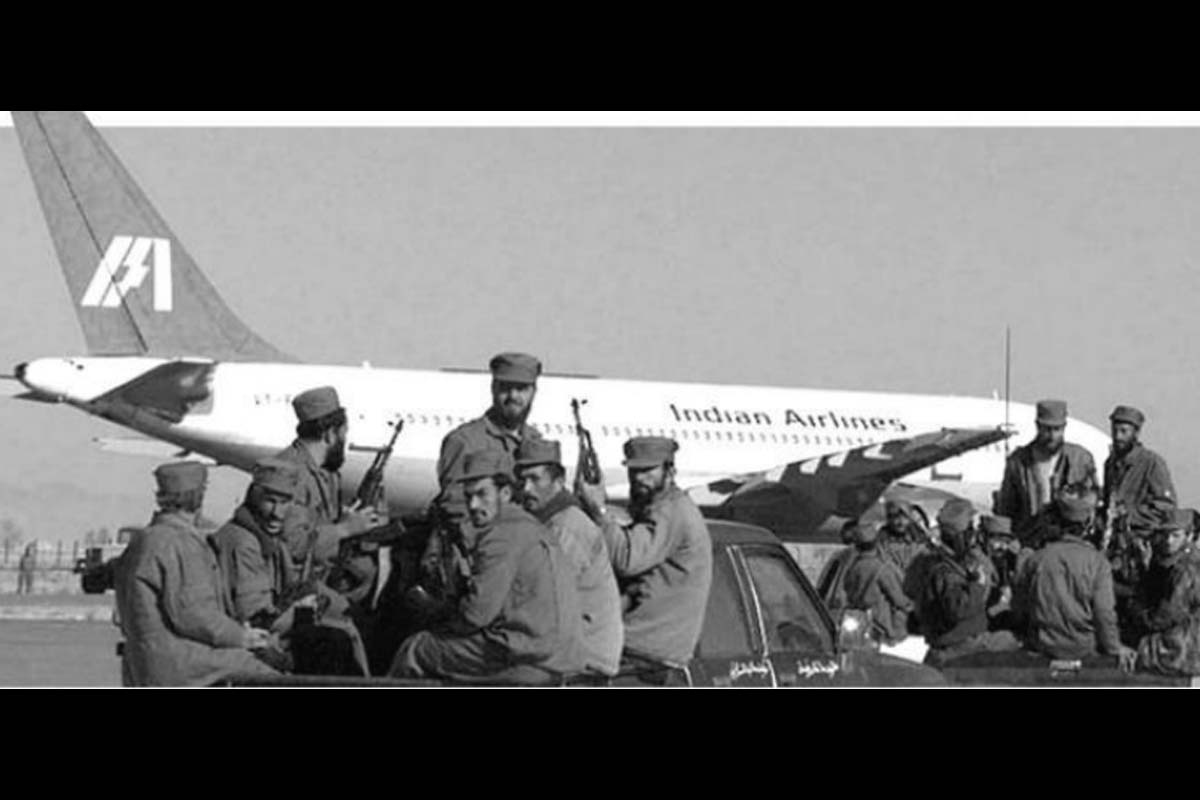

An airplane hijacking isn’t an ideal instance to dwell on the significance of management. But nonetheless, there is one such episode that offers crucial lessons on how importance management is, not only in dealing with crises, but also in running a country. We refer to the hijacking of Indian Airlines flight IC-814 travelling from Kathmandu to Delhi in December 1999.

The flight, with 178 passengers and eleven crew members on board had been hijacked by five armed men. Denied permission in Lahore, Pakistan, the plane landed in nearby Amritsar at around 7 p.m.

Advertisement

The hijackers demanded the release of 36 Islamist terrorists then held in Indian jails and a ransom of 200 million dollars. Prime Minister Vajpayee was mid-air, returning to Delhi from an official tour. In the Prime Minister’s absence, a crisis management group or CMG had been set up with senior officials and heads of intelligence agencies.

The cabinet secretary was formally in charge. The CMG scurried like a chicken whose head had been sliced off. IC-814 took off from Amritsar 45 minutes later and without it India lost any chance of regaining control of the plane inside our own territory. An official present at that particular meeting later said: ‘I was present in that room, and there was nothing but indecision.’

In theory, the decision is with the Home Minister. The hijacked flight flew to Lahore then Dubai and finally landed in Kandahar in Talibanheld Afghanistan.

Exhausted after a week of negotiations, Vajpayee decided to release three Kashmiri terrorists in return for the passengers. The finer details are laid out in the book Jugalbandi by Vinay Sitapati, published by Penguin Viking (2020).

Just imagine what an incidence of colossal mismanagement this was. But it also underlines the fact that like corporations and enterprises, the administration of countries too needs management. No one seems to have attempted to write a thesis on how to manage a country.

Lately, some hospitals and schools are being professionally managed. Mumbai’s Jaslok Hospital, which began treating patients in 1973, was to my knowledge, designed with the help of the management department of Messrs Ferguson & Co.

There is a growing awareness that professional management is an indispensible pillar of any collective activity, be it business or charity. One’s country needs systematic management but hardly anyone seems to have attempted such an approach.

Rulers govern their countries well or badly as their abilities enable them to do. In fact, there was no management science until World War I.

The German army headquarters happened to do an exercise on the number of combatants they had and how many men were deployed to support the men who fought on the battlefield. The study revealed that the Germans had four men supporting every fighting soldier.

In contrast, the British had ten men for every combatant. This meant that the British were two and a half times more expensive than the Germans in this respect. That is believed to be the beginning of the conception of management science. After the war, academicians got interested, especially in the USA; gradually, management science became a subject. During World War II, studies were conducted and business management schools began coming up after the 1950s. Peter Drucker rose to fame as a management scientist.

Yet it was the best teacher who usually became the school principal and the best professor the head of a college. In hospitals, the best doctor was made the dean. It was as though these institutions did not need specialised management. In the bargain, the best teacher or doctor got lost in the labyrinths of administration not really knowing what to do. If they showed earnestness in administration, studies would be neglected to an extent.

In India, to my knowledge, Jaslok Hospital in Mumbai 1972- 73, before taking off had followed a consultant who had advised how to design, arrange and manage the hospital, leaving the medical aspect exclusively to the doctors.

A chief accountant and chief administrator were appointed. In the bargain, the hospital worked efficiently. Gradually, the idea has been picked up by others. Yet if funds are short, a college or a school would rather not reduce a teacher but put off appointing a professional manager, and make do with a head clerk and call him or her manager, if the rules so require.

How important management is for any group activity is yet not fully realized.

The entire country is far more important than individual institutions, whether corporates, schools or hospitals. Yet there does not seem to have been any attempt at forging a science of national management.

How to manage a country? Such an attempt is overwhelmingly important also because there is no qualification required to get elected to either state assemblies or Parliament.

Thus, men and women who get elected are a mixed bag.

They are from various backgrounds and have different levels of education.

The bureaucrats, on whom the ministers tend to depend for advice, ideas and execution, are educated. But they might come armed having studied languages, mathematics or philosophy. Lately, even medical doctors and engineers are joining the IAS and other services.

Thus the bureaucrats too as a group are a mixed bag and would benefit by knowing how to manage their country or parts of it. Yet they begin work on the premise that they are competent to handle any portfolio.

They are supposed to be what in Urdu are called harfan maula or jack of all trades. In the absence of the knowledge I am pleading for, odd things occur at the cost of the country. Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, on the morrow of Independence, told General Lockhart, the interim head of the Indian army, “We (India) are a peaceful country and do not need an army. The police are sufficient to defend us”.

Nehru’s defence minister VK Krishna Menon once got so carried away while addressing the UN General Assembly that he went on and on and finally fainted in the Assembly itself. The following week the popular American weekly TIME had Menon on its cover with a caption underneath calling him a “spitting camel”. India’s sound case on Kashmir was thus spoilt. When the Chinese invaded our country in 1962 and looked like celebrating Christmas in Kolkata, Prime Minister Nehru came on All India Radio and said: “My heart goes out to the people of Assam”.

In Hindi, he said “Assam khatre mein hai” and seemed to be weeping. One can imagine how demoralizing this must have been for the people. Rather than reassuring them, he only further depressed them, throwing them into panic.

Another prime minister, years later, was asked by a journalist as to why India was not paying sufficient attention to tourism, to which his reply was that, “We are too large a country to worry about tourism!” Yet another prime minister, much touted as an economist, even went to the extent of declaring on television that the Muslims of the country must have the first claim on 15 per cent of the country’s resources! The epical conversion of an ordinary city state to a little jewel of Asia is the creation of a leader named Lee Kuan Yew.

A 640 square kilometre city, Singapore was a British colonial trading post with a population of less than two million in 1959. Within 40 years, its per capita income rose from 400 US dollars to 22,000! What a miracle? As Lee has written: public order, personal security, economic and social progress and prosperity are not the natural order of things especially without any natural resources. He calls this saga of Singapore ‘From Third World to First’.

After World War II ended, many such third world countries sprouted. But there was and is until today no book to guide them to rise. Lee had to dream and discuss with a few colleagues to convert the ideas into a reality.

The writer is an author, thinker and former Member of Parliament.

Advertisement