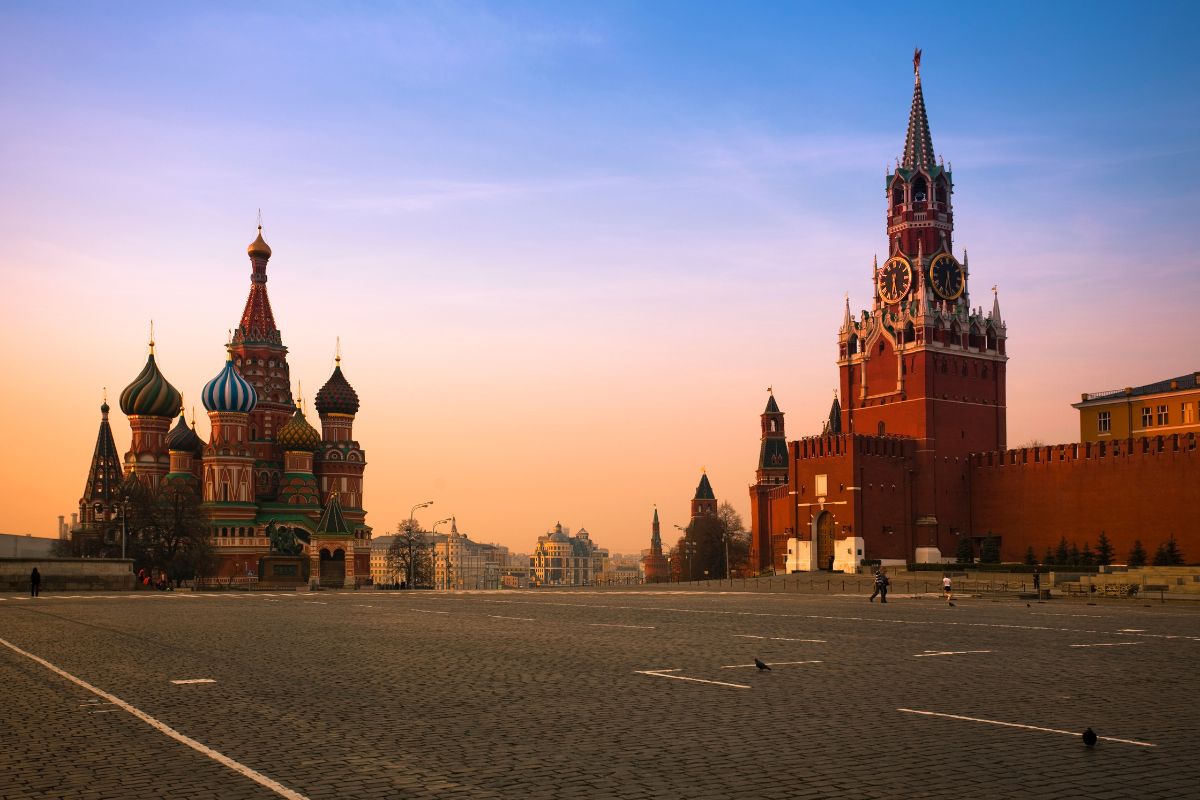

Kremlin warns against potential nuclear deployment in Poland

Russia will take necessary measures to ensure its security if Poland deploys nuclear weapons, Kremlin spokesman Dmitry Peskov said.

Understanding this context is key to making sense of President Vladimir Putin’s decision to invade Ukraine in February this year.

Image source (iStock)

As early as in 2014, strategic thinker Anthony H Cordesman stressed the need to understand rival views of grand strategy and military developments or, to quote a British military expert, “the other side of the hill”. Cordesman was writing in the immediate aftermath of Russia’s annexation of Crimea as he observed a range of Russian and Belorussian military and civil experts present a very different view of global security and the forces behind it from that of the West’s at the Russian Ministry of Defence’s Third Moscow Conference on International Security in May 2014. The standout point of his published paper was the laser sharp focus he brought to bear on the role of what Russian analysts termed the “Colour Revolution” in the evolving security situation.

The Kremlin saw a clear link between the “Rose Revolution” in Georgia (2003), “Orange Revolution” in Ukraine (2004), and the “Tulip Revolution” that took place in Kyrgyzstan (2005). The regime changes that followed these protest movements in the erstwhile Soviet republics caused considerable consternation, and even alarm, in Moscow. Russia tied the term Colour Revolution to what it saw as a new American-European approach to warfare that focused on creating destabilising revolutions in other nation-states as a means of serving their security interests at low cost and with minimal casualties. It was seen as posing a potential threat “to Russia (in its near abroad), to China, and to Asian states not aligned with the USA”. Understanding this context is key to making sense of President Vladimir Putin’s decision to invade Ukraine in February this year.

Russia-watcher Timothy Frye’s recently released book, Weak Strongman: The Limits of Power in Putin’s Russia, examines the roots of Mr Putin’s power and its implications for the country’s foreign policy. He underlines that Moscow’s more assertive foreign policy and the trade-offs being made ~ and largely being accepted by the Russian people ~ between security and economic growth seem here to stay. Scholar Andrew Monaghan iterates in his review of the book that the Russian leadership’s longstanding concerns about a Colour Revolution have not only been a dominant feature of the security debate in Moscow but also relate to the direction of its “personalist autocracy”.

Advertisement

The Kremlin’s understanding of the evolving international affairs landscape ~ how it envisages a “post-West” world including a “Pacific 21st century”, its prioritisation of the Arctic, its worries about growing competition over the global commons, and the geoeconomic competition that Moscow sees as intensifying and driving conflict over the coming decade ~ will dictate not just the West’s relationship with Russia but also impact how the “new cold war” thesis plays out globally. As Monaghan writes, a discussion on Russia’s calculus behind its measures of war is now unavoidable. An honest engagement with the issue, however, could throw up uncomfortable questions for the West.

A version of this story appears in the print edition of the August 29, 2022, issue.

Advertisement