PM Modi slams DMK’s ‘anti-Tamil culture’, vows to expose its ‘dangerous politics’

Addressing a gathering in Vellore, Modi said that the DMK wants keep people of Tamil Nadu trapped in old thinking and old politics.

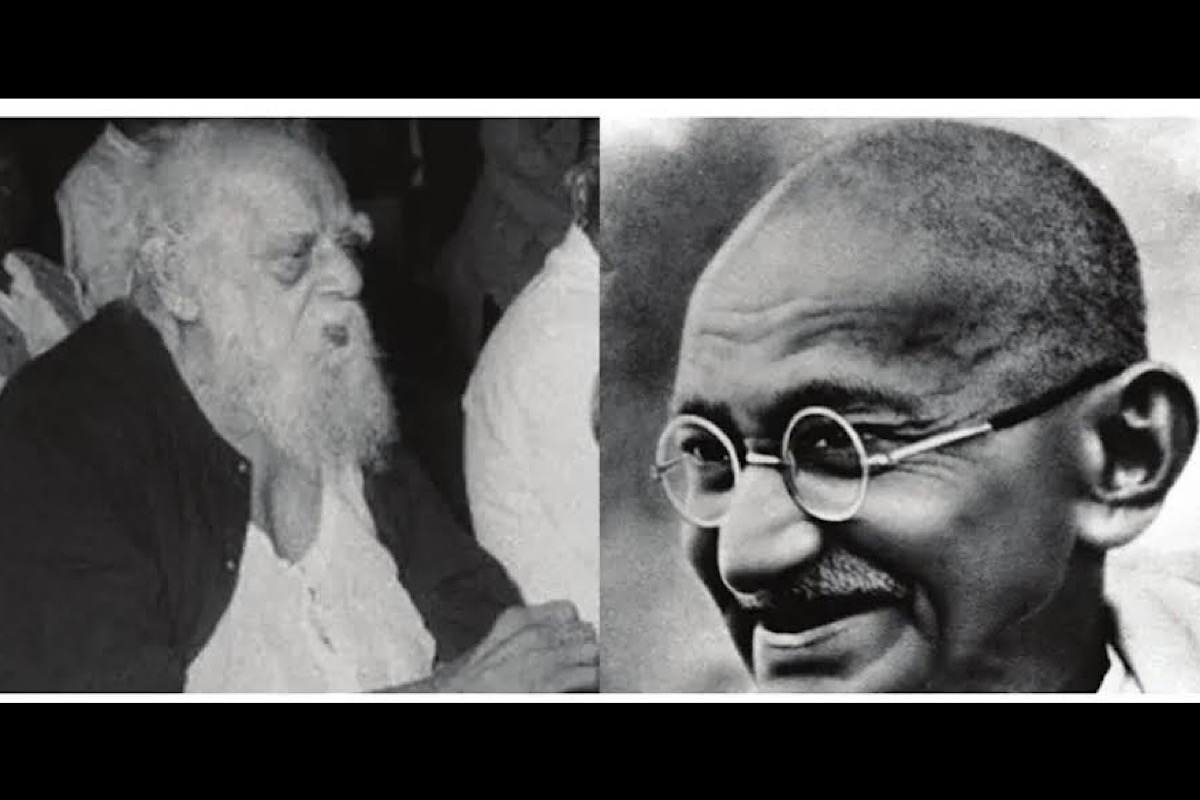

Periyar was initially an enthusiastic supporter of Gandhi from the very inception of the Non-Cooperation Movement as he was aware of the narrow social base of the Congress and the dominance of lawyers within it before Gandhi took charge. The advent of Gandhi was significantly transformative as his political and social activities were such that everyone could participate and his principles could ‘be understood by all‘. The atavistic orientation of Gandhian principles like khadi, prohibition and abolition of untouchability were refreshingly new and novel

Representation image [Photo:SNS]

Erode Venkatappa Ramasamy Naicker (1879-1973), popularly and reverentially known as ‘Periyar’ (the elder or respected one) or Thanthai (patriarch) was the architect of the Self Respect Movement and the founder of the Dravidian Movement and the Dravidar Kazhagam. His thought, along with Phule and Ambedkar, according to Omvedt “represents the effort to construct an alternative identity of the people, based on non-north Indian and low caste perspectives, critical not of the oppressive of the dominant Hindu caste society but also of its claims to antiquity and to being the major Indian tradition”.

17th September, his birthday is celebrated in Tamil Nadu as ‘Social Justice Day’. Periyar joined national politics in 1919 as a member of the Indian National Congress, inspired by Rajaji, with whom he shared a close friendship that was lifelong. He was an enthusiastic supporter of Gandhi from the very inception of the Non-Cooperation Movement as he was aware of the narrow social base of the Congress and the dominance of lawyers within it before Gandhi took charge.

The pre-Gandhi Congress also had little contact with the common people and was oblivious of their needs and aspirations. Writing in Kudi Arasu on 31 May 1925, Periyar described the early Congressmen as having “preyed on the blood of the land and its peoples.”

Advertisement

But the advent of Gandhi was significantly transformative as his political and social activities were such that everyone could participate and his principles could “be understood by all.” The atavistic orientation of Gandhian principles like khadi, prohibition and abolition of untouchability were refreshingly new and novel.

Periyar wholeheartedly supported Gandhi’s Constructive Programmes of social regeneration as these represented a “fundamental shift in the priorities of the Congress on the one hand and indicated the limits of habitual and agitational political activity”. He considered Khadi as an instrument to enhance the overall moral standard of all and the removal of untouchability as “the cornerstone of our Mahatma’s programme”. He was unhappy at the behaviour of the Swarajists for whom the Congress membership was one of convenience rather than conviction.

Being opportunistic and lustful of power, they provided token support to ameliorating major social contradictions within Indian society. He claimed that the term ‘Swarajist’ was incongruous and an understatement. He dismissed Srinivasa Iyengar’s criticisms of Gandhi because of his advocacy that lawyers give up their lucrative practice and opposed the Non-Cooperation Movement, even pleading that it should be declared illegal. Finding a wide gap between theory and practice he found lack of clarity even in Rajaji’s attitude, though he did not doubt his sincerity.

To tackle the problem of structured inequality, Periyar proposed proportionate (communal) representation as a practical solution but it was strongly opposed by the Brahmin Congressmen. He contended that if this basic demand was not met then the only way to end caste stigma would be to convert to either Christianity or Islam, a position like that of Ambedkar who himself became a Buddhist. He challenged the notion of Brahmin superiority as it was dismissive of the rest with no rights making their existence worse than animals. This menace could be fought by joint action of the non-Brahmins and the untouchables which was subsequently enlarged to include Christians, Muslims, Anglo-Indians, and other non-Hindus. Periyar was also conscious of the fact that though all non-Brahmins needed communal representation, the untouchables needed the most. Implicit in his understanding was the fact that caste played a crucial role in Indian society and was on par with class as the converted suffered as much as low-caste Hindus.

This proposition emphasized the cardinal importance of a politics of presence. If there were a sizable number of elected representatives and a larger number in government jobs, the untouchables would be able to demonstrate their strength and get rid of their present agony. Periyar provided three reasons for his parting with the Congress in 1927: (1) the Vaikom Satyagraha (b) the Cheranmahadevi Gurukulam happenings and (c) the debacle at Kanchipuram.

The personal experience of these three convinced him that the Congress, contrary to its formal adherence to represent all Indians, was essentially dominated by the Brahmins whose sole purpose was to protect and further the interest of their own community. But the final parting had yet to come. To the question as to why he delayed the severance of his links even after such a realisation, Periyar gave his reasons, (1) his continued faith in Gandhi, and (2) the belief in the NonCooperation Movement as a composite one catering to the needs and uplift of all communities.

He remained convinced that Constructive Programmes would resolve the deteriorating social relationship between the Brahmins and non-Brahmins. His advice to the people was to work for Constructive Programmes without joining the Congress. Destruction of Brahminism was at the heart of the self-respect movement and anticaste programmes. The cue for this came from Gandhi linking self-respect with swaraj which for Periyar meant abolition of untouchability. To eradicate the practice of untouchability meant doing away with practices such as prohibition of temple entry and worship.

Periyar compared these inhuman practices with the policy of apartheid in South Africa. Gandhi vehemently opposed apartheid but was not severe about prohibition of temple entry and worship. Swaraj was only possible with the attainment of social equality, dignity, and self-respect. It was in this context that he amended Tilak’s slogan of ‘Swaraj is my birth right’ to ‘self-respect is man’s birthright.’ “For Periyar”, according to Geetha and Rajadurai, “self-respect is man’s birth right and must precede swaraj or selfgovernment. Swaraj is possible only where there is already a measure of self-respect”.

Some important events hastened his departure from the Congress. These were (1) his fears of Constructive Programmes being placed on the backburner in view of the Swarajists’ decision to contest the general elections of 1927 which became clear at the Kanpur Congress of December 1926; (2) his anticipation of an increase in Brahmin dominance within the Madras Congress due to the impressive Swarajist victory in 1926 provincial councils as that meant greater control of the Madras Council which did not happen as the central leadership decided not to form the ministry; (3) the election of S. Srinivasa Iyengar as the Congress president in 1926 was a turning point as he was essentially conservative and was not an enthusiastic supporter of social reform and (4) his dismay at Gandhi’s disengagement from politics.

His biggest disappointment with Gandhi came when the latter publicly declared his belief in varnashrama dharma in July 1927 at Mysore. Periyar linked the persistence of untouchability to the continuation of varnashrama dharma itself.

He found a congruence between the view held by Brahmins in general and Gandhi’s and the latter’s silence on caste privileges strengthened his antiGandhi position. Both Gandhi and the Brahmins accepted the framework of the four varnas along with their functions. Periyar found Gandhi’s position untenable as the varna system, like the European guild system, ordained people’s destiny within a rigidly established group, confining each category to remain content and duty bound to perform the assigned function, one that passed on from one generation to another. He found Gandhi’s logic faulty.

Though he asserted that all the varnas were equal, he did not answer the pivotal question of wide differences in functional categories. He was also silent on another important question – that if anyone wanted to come out of this suffocating stratification, what were the opportunities and escape routes that were available? Periyar added that he and S. Ramanathan spoke to Gandhi and asked for his leadership to end the Brahmin hegemony within the Congress but Gandhi declined.

This deliberation convinced them that Gandhi believed in varnashrama dharma and wanted its perpetuation. He felt the need to provide a strong rebuttal of ‘political Brahminism’ that Gandhi allowed to perpetrate. Declaring his commitment to the ideals of freedom and selfrespect, Periyar refused to meet Gandhi again. Even earlier at the Vaikkom Satyagraha, where Gandhi took a mild approach, Periyar had strong reservations.

But his anger was more towards the local leaders of the Congress. His radicalism was at the opposite pole of Congress’ cautious and deliberate policy to conceal rather than find a solution to major social contradictions in Indian society. At times, it was mere symbolism.

(The writers are, respectively, a retired Professor of Political Science, University of Delhi and Professor of Political Science, Jesus and Mary College, Delhi)

Advertisement