India must focus on Israel-like ironclad defence systems: Anand Mahindra

India must focus on getting Israel-like ironclad defence systems, said Mahindra Group Chairman Anand Mahindra on Sunday.

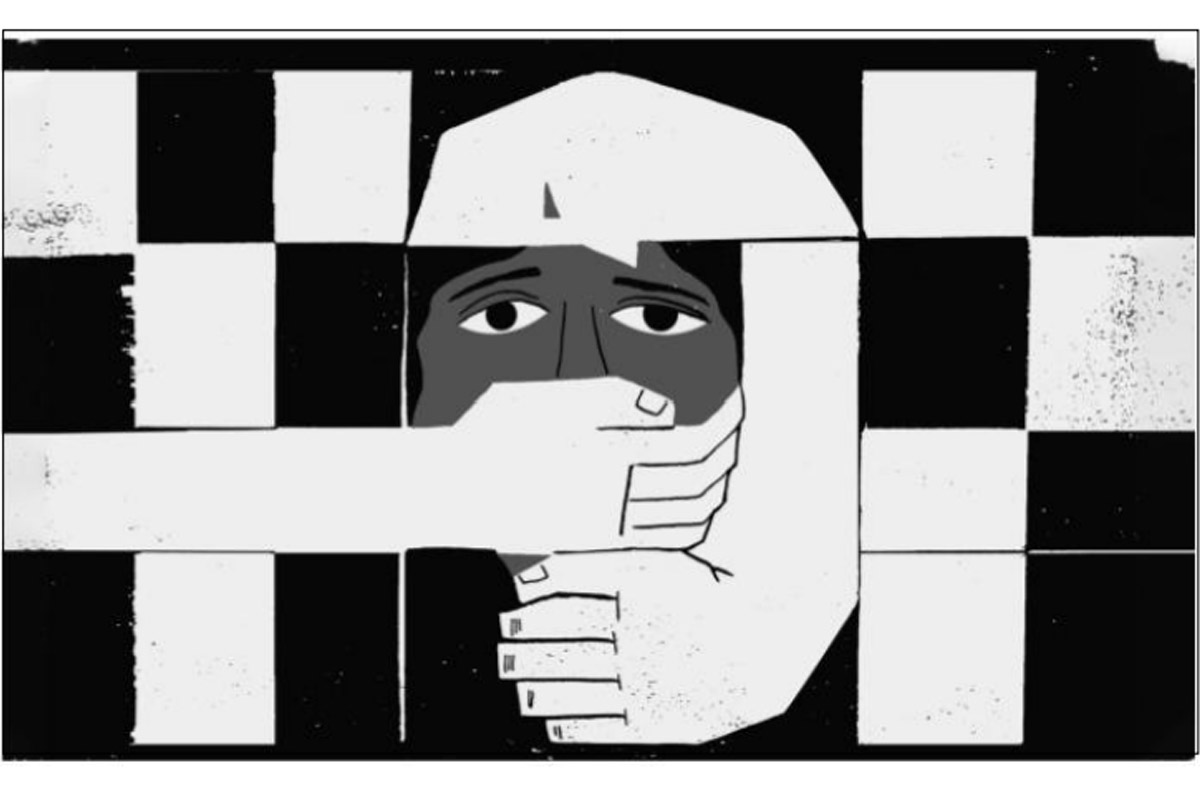

“Trafficking is the most egregious violation of human rights”, declared Kofi Annan, former UN Secretary General, at the turn of the new millennium, when the global body adopted a convention against transnational organised crime, and three protocols, one for preventing and punishing trafficking in persons, especially women and children, under the guardianship of the UNODC. So far, 177 countries, including India, have ratified it.

Sonu Punjaban @ Geeta Arora’s sentencing for twenty-four years, perhaps evoked little or no curiosity. But her name induces instant recognition in the crime world as ‘Delhi’s flesh trade don’. Slapped with many cases, her present conviction is for kidnapping a 12-year-old schoolgirl from Haryana in 2013, torturing and drugging her, and selling her to different sex agents in Delhi, UP and Haryana. Many Bollywood filmmakers drew story lines from Sonu’s crime-filled life.

“Trafficking is the most egregious violation of human rights”, declared Kofi Annan, former UN Secretary General, at the turn of the new millennium, when the global body adopted a convention against transnational organised crime, and three protocols, one for preventing and punishing trafficking in persons, especially women and children, under the guardianship of the UNODC. So far, 177 countries, including India, have ratified it. Yet in 2016, around 40.3 million were found to be victims of human trafficking – 71 per cent women and girls, and 29 per cent men and boys.

In 2019, a Supreme Court appointed panel estimated that around 950,000 people, 60 per cent of them women, and about 200,000 children, had been reported missing from 2016 to 2018, and said that it was ‘difficult to ascertain whether someone’s disappearance is intentional or unintentional…..’. It observed that “plausible reasons could be the lure of better living conditions in the face of extreme poverty, illiteracy and lack of opportunities”. Nonetheless, the Global Slavery Index, 2018 said that around eight million people lived in modern slavery in India in 2016.

Advertisement

Yet, India abounds in ant-trafficking laws. Apart from the overarching constitutional protection, the Indian Penal Code (IPC), 1860, has long enlisted well over twenty offences related to the trafficking of minors for commercial sexual exploitation (CSE) and forced labour and a bouquet of special acts like the Immoral Traffic (Prevention) Act (ITPA), 1986 and the Bonded Labour System (Abolition), 1985 also exist.

“Despite the ubiquitous legal shield… trafficking continues unabated… and minor girls remain the worst victims,” rued Rishi Kant, Director, Shakti Vahini, a Delhi-based NGO working against trafficking. It rings so true when we listen to the ordeal faced by Manisha (name changed), a fifteen-year-old girl, kidnapped from her village in North 24-Parganas in West Bengal in May 2019, pushed into a trafficker’s den in Delhi, traded with many sex brokers, and finally, rescued from a brothel in Silchar in Assam.

Similar was the fate of Rukhsana (name changed), another teenager from Azamgarh in Uttar Pradesh, who was duped by a local man with the false promise of marriage and left home with him in January this year. She was sexually abused for days together by him, and eventually forced into prostitution. Rukhsana was tracked down from a sex den in Mathura.

Nevertheless, the National Crime Records Bureau’s latest available data recorded a total of only 8,132 cases under the IPC, mostly (45.5 per cent) for forced labour and (21.5 per cent) for sexual exploitation in 2016. Amitabh Srivastava, a veteran journalist with experience of working with an anti-trafficking agency, brushed off its figures saying that “they do not reflect the reality and authorities taking solace in them are showing an ostrich like attitude.”

A global NGO’s anti-trafficking campaign head in India concurred, saying that “there is definitely (a) gap in data… the official data only reveal reported cases… many cases remain unreported… parents are hesitant or sometimes they are complicit.” A lawyer handling trafficking cases stressed that “unless the system of filing the FIR, Charge sheet is digitised, accurate data will not come into the system.”

Both the IPC and ITPA have critical gaps in implementation, lament legal experts and activists. Mr Colin Gonsalvez, a noted lawyer in Delhi and founder of HRLN, contended that “trafficking thrives with police patronage… existing laws vest enormous discretionary power with the police… each state police functions in its own way…unless there is a federal agency like the CBI, laws will not have the desired deterrent effect.” Others have deplored that India’s innovative labour laws largely remain on the statute books.

However, India earned some brownie points by piloting an exclusive anti-trafficking legislation in 2018, which pushed it up as a ‘Tier 2’ country in the U.S. State Department’s Trafficking in Persons report, 2019, from the earlier ‘Tier two Watch list’. Even the 2018 bill earned criticism for “creating a parallel legal framework… by retaining all other existing laws and… following the typical raid-rescue-rehabilitation model.”

Dr Ravi Verma, Director, ICRW, Asia, asserted that “since trafficking is a complex socio-economic phenomenon, it requires a well thought out process of social integration for victims, but one should not overlook the other side of it, many victims get sucked in to it… evolve a coping mechanism…they should not be dehumanised and denied the basic rights for survival.”

Crime in India, 2018, reported a 30 per cent rise of sexual harassment incidents in shelter homes for protection of trafficked victims and they mostly come into news for wrong reasons. Nonetheless, Deepshikha Singh, coordinator of a Delhi shelter home managed by Prayas, an NGO, which runs 38 homes across the country, maintained that “it is a big challenge… to help traumatised girls overcome the stigma and learn life skills.”

The experiences of Palak and Khushboo (names changed), two former inmates of Prayas, speak volumes about the tortuous journey they had to traverse at a young age. Palak, a tribal girl from a poor illiterate family in West Bengal, was brought to Delhi and her traffickers were her relatives, neighbours and even her teachers. She landed up in domestic servitude with an oppressive employer. While trying to escape, she fell into the trap of sex racketeers and was ultimately rescued at New Delhi Railway station by Prayas’s team. Khushboo, a school drop-out from Bangladesh, was lured by a group of friends she befriended while working in a garment factory and assured a job as cosmetics salesgirl in Dubai. She found herself in Delhi. She was rescued by Delhi Police when trying to run away.

“Palak sustained severe internal and external injuries…received medical attention, got her unpaid dues and her employers were arrested…Palak returned to her family after staying for four months. Khushboo, during her six-month stint at the home, learnt the finer qualities of life like art, theatrics and dance and also professional skills of a beautician….she rejoined her family with the help of the Bangladesh High Commission and the Bangladesh Women’s Lawyer’s Association (BNWLA),’’ Ms Singh informed.

She admitted that “families are always not keen to take back the girls, it requires multiple sessions with the child and family and also a follow-up process”. A NHRC study corroborated that “a vast majority of re-trafficked survivors (80 per cent), revealed that they have not been able to find any alternative livelihood options …when they returned to their communities.”

Now, when the world is ravaged by a raging pandemic, the UNODC’s warning that “traffickers are waiting for this opportune moment…likely to prey on vulnerable people” rings an alarm bell. In India, an MHA advisory has alerted states to strengthen antitrafficking units. A Centre for Science and Environment study has anticipated “an addition of 12 million poor in India as a pandemic fall out.”

Rishi Kant of Shakti Vahini also raised concern that “traffickers are on the prowl(as) this extreme calamitous situation is a breeding period when they look out for potential targets, befriend them, more so in a lead source state like West Bengal, which suffers from the dual impact of Covid19 and a devastating cyclone.”

No doubt, the malaise is deep-rooted in India with rising rural distress, forced migration, unregulated labour market and gender discrimination and needs a fundamental overhaul, not a cosmetic change.

The world anti-trafficking day passed a few weeks ago. As the UN forewarned, trafficking “an abhorrent practice is still prevalent in all its insidious forms, old and new.” Isn’t it high time to take a serious call to counter trafficking in a pandemic whacked world?

The writer is a retired Indian Information Officer and a media educator.

Advertisement