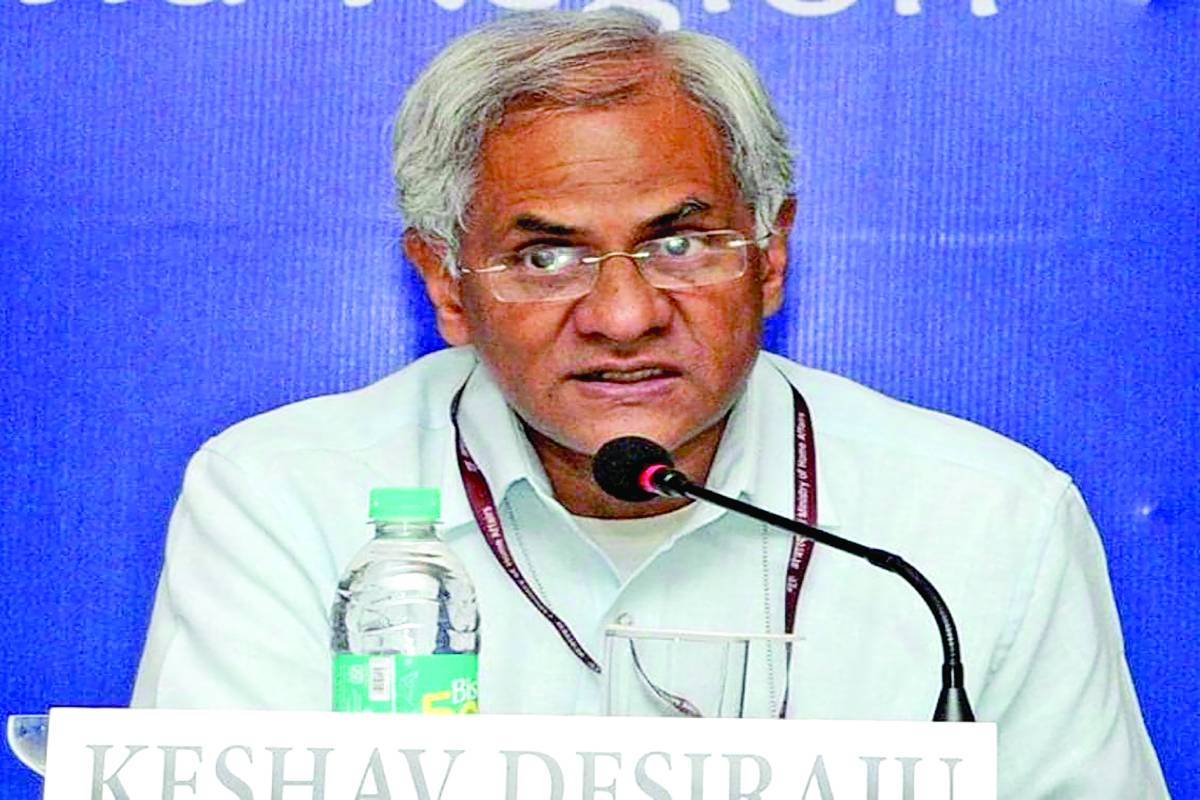

Death reminds us of the transience of life, and with the demise of a close friend, we also lose a part of our universe associated with him. Keshav Desiraju, an IAS officer of 1978 batch (Uttar Pradesh /Uttarakhand cadre), has left his friends and acquaintances to mourn his passing at the age of sixty-six. The stream of tributes carried by every major newspaper indicates how much this quiet man touched the lives of others. Most of the obit pieces highlight his role in formulating the bill for mental healthcare during his tenure as Union Health Secretary. Some others have extolled his human qualities. But there have been umpteen civil servants whose contributions have been far more significant. I know of many who were as humane and empathic with people they came in contact with. What then were the attributes that made Keshav so unique? First, his sense of purpose. I met him in August 1987 when I joined the faculty of L.B.S. National Academy of Administration in Mussoorie. We occupied the same residence, divided by a thin partition. His portion was always humming with activities of IAS and other probationers. It appeared unusual that Keshav knew most of them by name and their background and nature. This showed his interest in every individual. Besides, he worked towards integrating the role of non-governmental, grass-root organisations into the training framework. Also, he emphasised the need for cultural nourishment for the wholesome growth of young minds. Keshav would know all about Tushar Kanjilal, the social activist and environmentalist at Rangabelia in Sunderbans region, as about Kesarbai Kerkar. This sense of purpose and an abiding interest in fellow beings would inform everything he did. His stint at the Academy was a turning point and deeply influenced his course of life. Second, his equanimity and sense of fair play. As an apolitical officer, he faced the usual highs and lows that he accepted with grace. He worked as a District Magistrate at Almora, and in the ministries of environment, personnel and school education before he moved to the health sector, his gentle exterior concealing his resolve to stand by the right causes When a senior IAS officer wanted to get her date of birth changed in order to gain a few more years in service and brought pressure, Keshav had gone an extra length, in his gentle way, to resist the pressure and reject the request. There were many such instances, lying buried in files, where he consistently sought to defend the bureaucratic ‘dharma’. And, sometimes he had to pay a price for such action. Third, his clear perception of self and others. Conscious of his own strengths and limitations, he could use the former to advance what he held dear. More a thinking bureaucrat than a slogging one, he focussed his energy on select areas, and pushed such priorities hard. Endowed with an acute mind, Keshav was best suited for ideation – as reflected later in his role as a policy maker. Aware of the deficiencies of ‘sarkari’ processes, he strove to expand the boundaries of government action to accomplish what really constitutes public service. He was convinced there are important players, especially in the social sector, whose voice should be duly recognised and mainstreamed. Against this perspective, the inkling that he was extra sympathetic to NGOs and civil society activists would appear unfounded. Fourth, his sense of balance. Keshav was even-handed in his appraisal of men and matters, being averse to anything crude, distasteful, or extreme. While certain actions of the current government, especially on contentious issues related to social exclusivity and reported violation of human rights, troubled him, he once told me, in a lighter vein, that few things have been done in recent times the likes of which had not been attempted earlier. He disapproved of any brazen exercise of power whether stoked by majoritarianism or other forces. As a career civil servant, he had seen them all and, therefore, his perceptions were defined more by constitutionality and his bureaucratic self than by political ideologies. Fifth, the freshness of his mind. Unlike most of his colleagues, he retained this quality on account of his association with an expanding circle of friends (of both sexes), and his wide- ranging interests in books and music. The last time we met at the India International Centre, he was finalising the draft of his book on M.S. Subbulakshmi, and was simultaneously busy reading The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks. We always talked of new books, the latest being Jairam Ramesh’s remarkable work on The Light Of Asia. Finally, he truly valued and nurtured friendship. Keshav led an unusually enriched life, widened by his education at Bombay, Cambridge and Harvard. He was always full of stories, fun and quality gossip. Moreover, he possessed the ability to maintain discrete spaces in his mind for friends of all hues. Sophisticated and sensitive in nature, he knew the interests of others. I will cite just two examples. Once we talked about the great academic philosophers of modern India, his grandfather Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan and Professor Surendranath Dasgupta. A few days later, he sent me Radhakrishnan’s review of a volume of Dasgupta’s A History of Indian philosophy, published in The Hindu in the 1930s. He knew more about Satyajit Ray than most others, and a few months ago, shared with me the cover designed by Ray for Sarvepalli Gopal’s biography of Jawaharlal Nehru, adding that it was not used and that it adorns the wall of his aunt’s (Gopal’s wife) bedroom in Chennai. This is how he remained meaningfully connected with all friends. During our last, long conversation a few weeks ago, we discussed many things including the personal. I briefed him about some minor errors in his masterly work on Subbulakshmi. He said he had received many suggestions and wanted me to send mine early. Keshav was very pleased with the success of this book (he had earlier co-edited a volume on healthcare corruption in India) and the reviews it generated, agreeing with me that the critique by Arvind Subramanian was among the most perceptive. While preparing to write his next book on Thyagaraja, he left us all too suddenly. Keshav embodied many qualities, being civil and scholarly, brilliant and humorous, friendly yet private to the core. All combined, a sparkling public servant whose memory will take time to fade.