Justice delayed is justice denied: Yogi Adityanath on Ram Janmabhoomi

He said in the interim transitionary phase the holy men should boost positive efforts to strengthen peace and harmony in the country.

The judiciary needs to set its own house in order. Lower courts have their own momentum; they are often guided more by convenience and local circumstances rather than by the spirit of directions issued by superior courts.

The Preamble to the Indian Constitution enjoins the State to “secure for all its citizens: Justice, social, economic, and political.” The Directive Principles of State Policy reiterate this concept; Article 39A reads: “The State shall secure that the operation of the legal system promotes justice, on a basis of equal opportunity … opportunities for securing justice are not denied to any citizen by reason of economic or other disabilities.” However, judicial delays often defeat the right to justice except for the few who can hire expensive lawyers to pump-prime the system. For the rest, a foray into litigation is guaranteed to drain one’s resources, with a decision being obtained when the need for the remedy is probably over.

Innocent undertrials are often released from jail only after undergoing a major part of the sentence prescribed for the guilty. Judicial delays entail huge economic costs: Economic Survey 2017-18 and Economic Survey 2018-19 had entire chapters explaining how judicial delays were holding back economic progress and were a reason for our low rank in Ease of Doing Business.

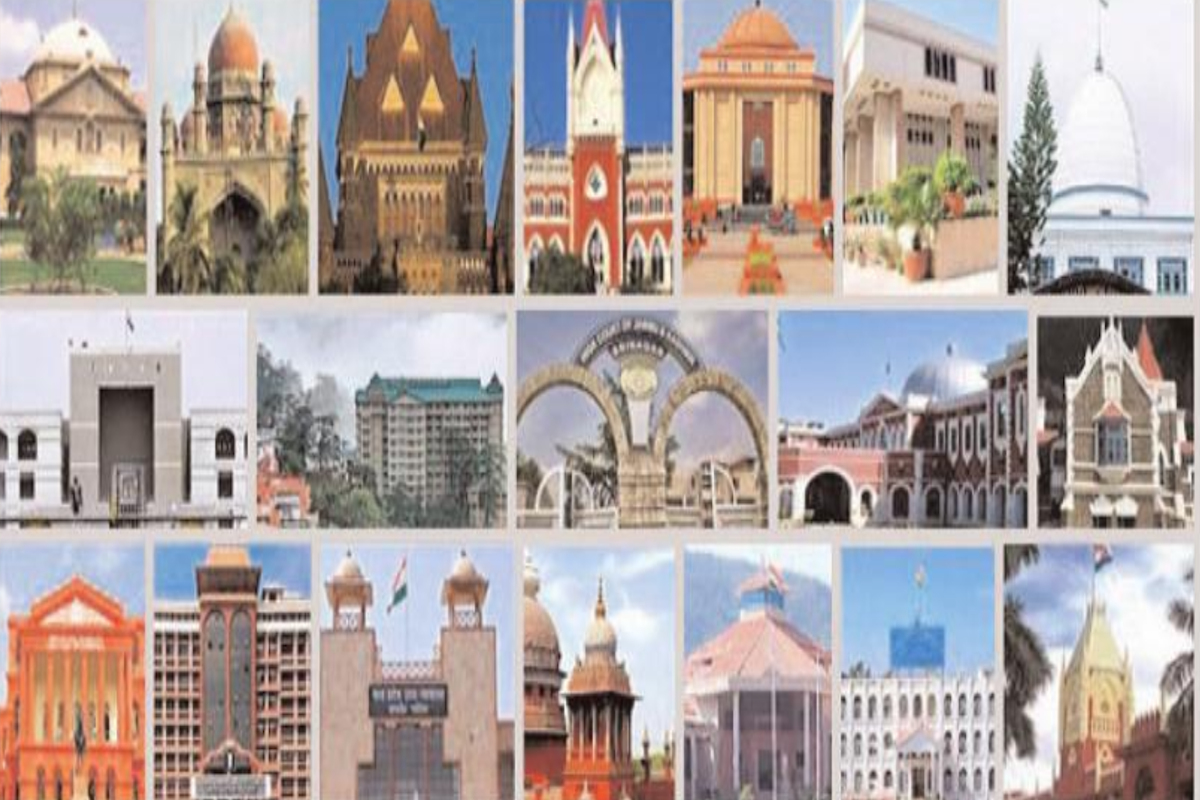

The travails of the judiciary were discussed threadbare in two recent high-level Conferences; the 39th Conference of Chief Justices of High Courts, chaired by the Chief Justice of India, followed by the Joint Conference of Chief Ministers and Chief Justices, which was inaugurated and addressed by the Prime Minister. Both Conferences aimed to address issues concerning the judiciary and the action that needed to be taken to improve the justice delivery system. Supposed to be held annually, both Conferences were held after a gap of six years.

Advertisement

A host of issues ranging from poor infrastructure in courts to the use of local languages in court proceedings were discussed. Addressing the Joint Conference of Chief Ministers and Chief Justices, the CJI flagged ambiguous laws and non-performance of the various wings of the executive and judicial vacancies as prime reasons for the malaise afflicting the judicial system. The Prime Minister suggested writing laws in simpler language, use of local languages in Courts, increasing the use of technology in judicial processes, encouraging mediation and providing easy bail to undertrials. The CJI talked of the recent appointments of 126 High Court judges while the PM pointed out that the Centre had abolished 1,450 obsolete laws during his stewardship. But the increasing caseload in District Courts ~ which had increased from 2.65 crores to 4.11 crores between the last Conference and the present one ~ was not given the attention it deserved.

To bring down pendency, the CJI, inter-alia, suggested increased recruitment of District Court judges, the temporary appointment of retired High Court judges and the creation of a national-level body to augment court infrastructure. Reportedly, the last two suggestions have been rejected by the Government. Interestingly, recruitment of more judges for manning District Courts was also suggested by the Economic Survey 2018-19 which claimed: “… a case clearance rate of 100 per cent (zero accumulation) can be achieved with the addition of merely 2,279 judges in the lower courts and 93 in High Courts, even without efficiency gains.” However, this solution is not likely to work.

In his address to the Joint Conference of Chief Justices and Chief Ministers the CJI pointed out (though in another context) that the sanctioned strength of judicial officers had increased from 20,811 in 2016 to 24,112 in 2022 (an increase of 16 per cent), yet during the same period, pendency of cases in District Courts had gone up from 2.65 crores to 4.11 crores (an increase of 54.64 per cent). In any case, an increase in sanctioned strength has to be accompanied by the recruitment of judges and their supporting staff, creation of infrastructure, like additional courtrooms, allotment of jurisdiction etc ~ all of which are time-consuming processes.

However, genuine cooperation between the three branches of Government ~ the Executive, the Legislature and the Judiciary ~ can rid Courts of the accumulated mountain of cases and prevent the accretion of new ones. As pointed out by the CJI, the Executive could help by sticking to rules and avoiding actions that test the borders of legality and the Legislature could frame laws in a better fashion. Laws circumscribing personal choice in matters of food, drink, marriage and religion, enacted by some state legislatures recently, prescribing long prison sentences for alcohol consumption, cow slaughter and consumption of beef have brought millions of cases in their wake.

The Chief Justice of Patna High Court had to write to the Chief Minister to point out that stringent prohibition laws had led to a flood of litigation in lower courts that left little time for judges for deciding more important cases. An earlier CJI had remarked that an amendment in the Negotiable Instruments Act had led to pendency of 60 lakh cases. Probably, following the Pre-Legislative Consultation Policy (PLCP) before introducing legislation and assessing the effect of the legislation after a pre-determined period would help in curbing the enactment of contentious laws (Legislation Reimagined, The Statesman, 14 December 2021). That said, it is the primary duty of public representatives to dis- cuss and debate all aspects of any proposed enactment and enacts laws that are acceptable to all.

Finally, the judiciary needs to set its own house in order. Lower courts have their own momentum; they are often guided more by convenience and local circumstances rather than by the spirit of directions issued by superior courts. For example: As part of its drive against the criminalisation of politics, the Supreme Court had constituted special courts to try cases against public representatives in January 2018. In September 2020, the amicus curiae assisting the Supreme Court reported that a total of 4,442 cases were still pending against MPs/MLAs in different courts, including Special Courts.

The progress in most cases was minimal, the oldest case in the Special Courts dated back to 1983, and three cases registered in 1991, 1993 and 1994 had not even reached the trial stage. Almost no one had been convicted by the Special Courts and most cases were still pending. For example, of the 245 cases in Telangana, 73 had been disposed of with no conviction and the rest were still pending. The situation was the same a year later, with 4,984 cases pending in Special Courts as of 1 December 2021.

Such instances abound because judges of lower courts, who are a demoralised lot with uncertain career prospects, have to satisfy both public sentiments and stand up to the powerful Executive. Most judges buckle down, leaving contentious cases undecided, and relying on technicalities rather than facts to decide cases. The Civil Procedure Code and the Criminal Procedure Code have several provisions like plea bargaining, compromise, trial by summary procedure etc. to aid quick disposal, which are seldom applied by courts.

Similarly, the timelines laid down in both Codes for the disposal of cases are seldom observed. Probably, more than anything else, District Court judges require moral support and reassurance, rather than constant criticism from higher courts, to dispense justice quickly and boldly.

Higher courts have failed to lead by example; the reluctance of higher courts, particularly the Supreme Court, in deciding cases with political connotations has sent a wrong message to the subordinate judiciary.

For example, a number of cases of disqualification of elected representatives, as also challenges to controversial Acts like the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA), are kept pending for a long. Perhaps, it would be better if the Supreme Court sheds its coyness and decides contentious cases quickly if only to show the right path to lower courts.

According to a 2018 strategy paper by Niti Aayog (New India @75), at the present rate of disposal, it would take 324 years to clear the backlog of pending cases, so an ordinary litigant can- not expect to get justice in his lifetime. Justice Ranjan Gogoi, a former Chief Justice of India, stated in an interview: “If you have to go to court, you will only be washing dirty linen in court and you will not get a verdict. I have no hesitation to say so. You regret it if you go to court.” Madan B Lokur, a retired judge of the Supreme Court was constrained to observe: “The Chief Justice of India has two options before him: (1) Take revolutionary steps with revolutionary fervour to remedy the malaise afflicting our justice delivery system, or (2) Be ready to light its funeral pyre.”

Hopefully, the Chief Justice would not have to resort to the second option.

(The writer is a retired Principal Chief Commissioner of Income-Tax)

Advertisement