Human-animal conflict declared as state-specific disaster in Kerala

In the wake of the recent tragic incidents of wild animal attacks on people, Kerala government on Wednesday declared man-animal conflict as a 'state-specific disaster'.

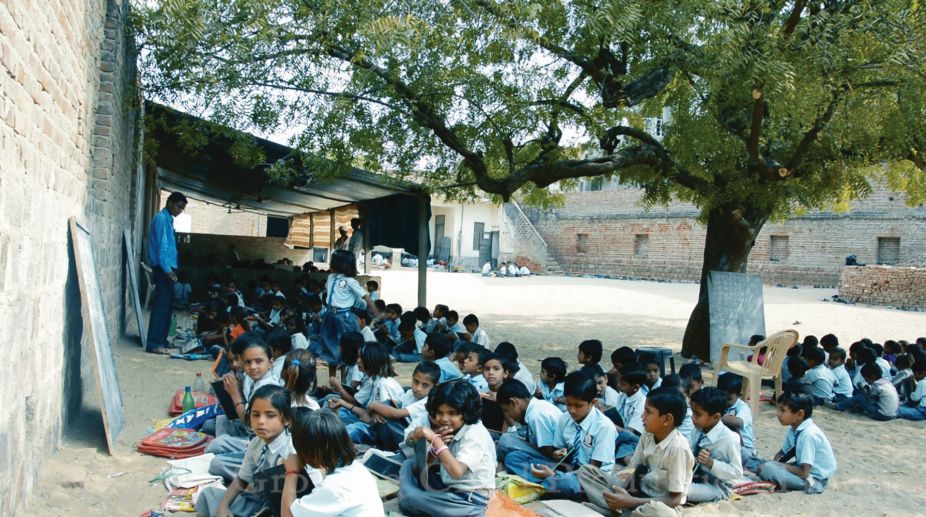

Children in Indian village school. (Photo: SNS)

Computer scientists were long obsessed with the idea of designing a computer with superhuman intelligence, a process which culminated in the development of the computer Deep Blue, which was able to defeat the reigning world chess champion Gary Kasparov in 1997.

Yet, belying science fiction fantasies of computers ordering humans around we still have not been upstaged by computers. Which says a lot about the depth of human intelligence and resilience of the human race.

India is extraordinarily lucky so far as human capital is concerned. Even when the Union Jack was flying high over the Red Fort, Indians were winning the Nobel Prize.

Advertisement

Indian soldiers contributed greatly to the British victory in both World Wars. In the 1990s, armed only with native intelligence and desktop PCs, Indians stormed the nascent software industry forcing the West to take note of India as a leading knowledge power.

Once it came into its own, our services sector was more than able to make up for the deficiencies in our manufacturing and agricultural sectors. Even today Indians power the Silicon Valley and Indians form the backbone of top tech institutions like NASA, Microsoft and Google.

However, in India, our rich human capital lies unutilised with our leaders trusting only technology or foreign experts. Perhaps, this is one of the main reasons behind the relentless flight of talent from our shores.

On the other hand, all failures of the Government and business are routinely attributed to the rapacity and inefficiency of lower level workers, which is not at all correct.

Most of the time the problem lies not in the quality of human resources but in their management. A prime example is our bureaucracy which over time has become inefficient and de-motivated.

In view of the fact that out of thousands who apply for a government job only a few are selected, we can safely infer that some of the most intelligent and capable persons are selected to work in the Government.

Additionally, government employees are subject to monitoring by myriad agencies; Departmental Vigilance, CVC, ACB and CBI to name a few.

Even then, if Government departments are perceived as corrupt and inefficient then the fault lies not with the employees but with the leadership and the procedures devised by them.

At present, we live in a halfway house; most large organisations follow hybrid procedures with one part of a business process being computerised but another part being manual, which gives us the worst possible of both systems.

A current example is the Nirav Modi fraud. Modi was able to defraud the Punjab National Bank of zillions of rupees because the software part of the processes was compromised by the junior bankers who were executing the manual part.

Had traditional bankers been running the show, they would not have lent to Modi beyond his actual worth.

They would also have asked him the source of funding of his foreign stores and would have easily found out that buyers’ credit was being misused to purchase real estate abroad.

In fact, a balancing of the Nostro account (in which the loans to Modi had been deposited) would have revealed Modi’s misdeeds before they reached their present humongous proportions.

At their inauguration, successive Governments talk of bringing about fundamental changes in the bureaucracy but all governments slowly get mired in the same red tape they had promised to cut.

Probably, no Government realizes that if you have the same people and the same processes then the same results would follow. Governance can only be improved if simpler processes are designed, people are given responsibilities according to their capabilities and most importantly, the honest are rewarded and the guilty are punished.

Instead of an endless blame game where the politicians blame the bureaucrats, the bureaucrats blame the politicians and the common man blames everyone in authority, proper processes and proper deployment of manpower would do wonders for our administration.

Another carefully nurtured misconception: “the discretion available to officers needs to be curbed to get rid of corruption” prevents us from utilising the intelligence, innovation and competence of our work force.

Rhetorically speaking, if no discretion is available to a public servant, it may be better to replace him by a robot or computer who would blindly apply rules regardless of the consequences.

Doubtless, there are instances where discretion has been misused but often in knee-jerk reactions, instead of acting against an errant officer, the available discretion is taken away from that class of officers.

An example readily comes to mind. In the Income-tax Department, initially, an Income-tax Officer (ITO) had full authority to select a case for scrutiny with the approval of his senior officer.

Most of the ITOs, who had good local knowledge, selected cases of persons who appeared to be evading taxes. Over time, some cases of irregular selection were reported to the higher authorities.

Instead of taking action against such officers, the Government slowly raised the level of authorisation so much so that on date there is no discretion available to any functionary to select any case for scrutiny.

Rather, cases are selected for scrutiny by a computerised process which picks up only 1 per cent of the returns that are filed in a given financial year. In this scenario, no use is made of the local knowledge or intelligence of officers.

However, when some scam breaks out, the Income-tax Department is accused of sleeping while the scamsters were making hay.

In a heavily overpopulated country like ours the use of technology can be justified only where something cannot be done manually or if technological processes yield far better results.

However, technology is often deployed without any such analysis. Thus, to counter accumulating dirt, many cities employ huge road-sweeping machines.

Besides being quite costly and putting a large number of low-paid employees out of work, these machines are hardly effective given the fact that most of our roads are narrow, broken and crowded at all times.

Then, we had the horrific experiment of weeding out bogus Public Distribution System (PDS) beneficiaries by linking ration cards to Aadhaar; which resulted in starvation deaths of some very poor people who were not able to link their ration cards to Aadhaar.

On the other hand, it was found that by using an unauthorised software programme, some PDS dealers were using beneficiary data to divert PDS grains to the open market.

It would appear that instead of nurturing our human capital, we are allowing human capital to decay. High infant mortality, poor nutrition and non-functional Government schools ensure that poor children face cognitive and educational challenges, reducing our gains from our demographic dividend.

When they grow up, our youth look up to the poor example of loan defaulters, tax evaders, and relatives of influential persons who appear to do well for themselves without doing anything.

To realise the full potential of our human capital, we have to foster a culture of excellence in every field because long years of poverty has given rise to a culture of “make do.”

As a result, we put up with anything; sub-standard schools, pot-holed roads, strange contraptions masquerading as cars and the like. We have to remind ourselves that we are an emerging superpower and that we have left behind those days behind when jugaad was a necessity.

We have to change our psyche from the mindset where the aim of students is to somehow acquire a degree but not to gain knowledge, where workers while away their time achieving a fraction of their possible output, where our agricultural productivity is a fraction of other countries.

The Government can help by giving human capital its due and adopting people-centric policies instead of concentrating solely on infrastructure development and ease of doing business. One is reminded of what Oliver Goldsmith wrote in The Deserted Village after observing agrarian distress in eighteenth-century Ireland:

Ill fares the land, to hastening ills a prey,

Where wealth accumulates, and men decay;

Princes and lords may flourish, or may fade;

A breath can make them, as a breath has made;

But a bold peasantry, their country’s pride,

When once destroyed, can never be supplied.

The writer is a retired Principal Chief Commissioner of Income-Tax

Advertisement