From now onwards, no meat shops allowed within 150 metres of Delhi’s religious sites

According to the announcement, the requirement of 150 metres from the Masjid (Mosque) will only apply to pork shops

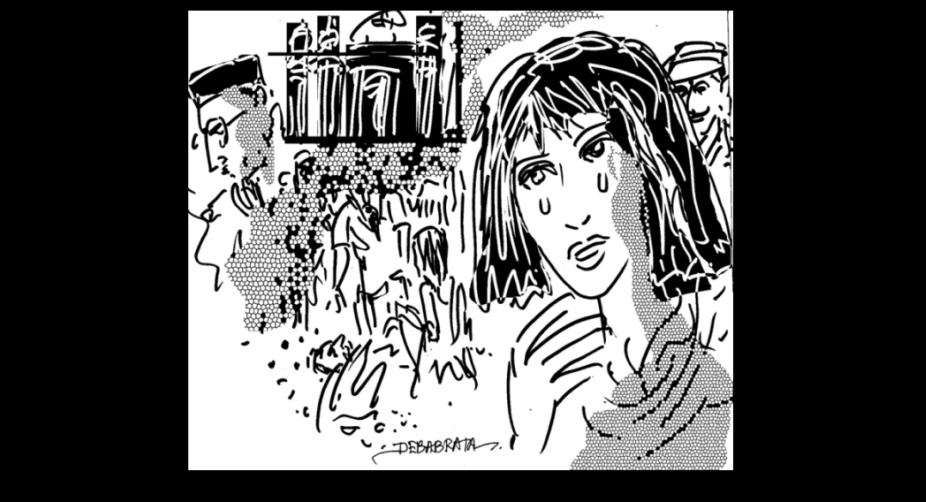

Gudia’s proficient father, Kallu, had already taught her the tricks of the trade — begging in this case.

A dead body lay abandoned near a dhaba, adjacent to Jagat

theatre in Delhi’s Chandni Chowk area. Seated by the side of the body was the

deceased’s daughter, Gudia — she was napping, leaning against the dilapidated

semi-moss milestone with her head resting on her tiny palm. Briefly, she would

yawn, rub her eyes and look at the nearby mosque. From behind the Red Fort, the

yellow rays of the morning sun gleamed on her vulnerable face, reminding,

rather commanding her to begin the day’s work.

Gudia, seven or eight years old, stood up. Her father was

never late at work and taught her to be punctual. She had to reach the near-by

Sunahri Masjid and beg for a few coins to have a cup of tea from Bismillah tea

stall, popularly called Ustad Chaiwale — a nickname for his mastery in making

and serving quality tea, fast.

Gudia’s proficient father, Kallu, had already taught her the

tricks of the trade — begging in this case. She knew her routine work but

something encouraged her to take liberty on account of her father’s absence.

Instead of going to the mosque, she would first take tea and then go begging.

She went to Ustad’s tea stall and asked for a cup. Still standing, Gudia waited

for Ustad’s usual rebukes, “Go away….Let the Maulvi Sahib or his companions

have tea first…First sale of the day must begin with pious people, not a thug

like you.” She had grown indifferent to such abuses. But today things were

different. Ustad did not chide her. Instead he compassionately said, “Come

along, my baby.” He lifted her up, kissed her and ran his hand affectionately

on her head before making her sit. “Why this?” thought Gudia.

Advertisement

Unknown tears flowed from her eyes and made their way

through the narrow dry lines that had appeared on her plump cheeks after

wailing the night before. Her lower lip pushed out; her nose widened a little

in her effort to control the tears. Cleaning her nose with her handcuff she

rose to retreat from the smoke-stained stall. She could not bear sympathy; she

was simply not used to it and she did not deserve it. But Ustad fondled her and

made her sit again. He gave her a glass of water and one big brown loaf to eat.

Gudia would not spend her penny for the loaf. Her father had

lessoned her to save money. “I don’t want the loaf, Ustad,” she mumbled in a

broken voice. She told him that she only

wanted tea and had no money to spend on bread. But she realised that her father

was dead now and that she was a free bird. She would take whatever she liked.

Nobody would admonish or thrash her. She would take the loaf and tea and puri

and halwa and whatever she liked. She had money. Her father had handed her the

small red clothe-bag — his one-day savings — before his death.

Even as Gudia was provided tea and loaf, Maulvi Sahib

arrived ordering a cup in a flat, phlegmatic voice. His blue-stripped muffler,

which was tightly wrapped around his heavy head coupled with a blanket covering

him from head to toe, gave the man an otherwise ghostly look. Gudia stood and

intended to get back to work. Maulvi Sahib asked, “O daughter of an

imposter…Where is Kallu? Why did he not come to beg today?”

“He is no more,” answered Gudia in an indifferent tone.

After a short interval, cogitating, she said, “My father had told me before his

death to go to Maulvi Sahib’s mosque every morning… He will always give you

coins. Now I will be coming to your mosque every morning.” Maulvi Sahib knew she was lying like her

father. But she was so small, so vulnerable, and at that time looked so cute

with her face dry and brown hair tousled, that something unusual had happened

to her.

Ustad informed, “Kallu had one crumpled blanket with holes

all around…The wretch could not save himself from the cold wind that blew last

night.” Maulvi Sahib murmured something in alien language. Ustad then added

pleadingly, “He left no amount for his last rites…Except this poor creature.”

“No problem, our men will do that”, said Maulvi Sahb asking

his companions around to arrange for Kallu’s funeral in the nearby graveyard.

He then headed for the chowk with a few others, along with Gudia, as passers-by

started assembling.

There were murmurs about her father’s last rites. One from

the crowd, who appeared to be a doctor from attire, said he needed a cadaver

and he was ready to pay money for it to his child. Looking at Gudia, he said,

“I will take care of her. Give her shelter.” The doctor held her tiny palm and

gave her a 500 rupee note to buy her assent. Before Gudia could say anything,

the Maulvi Sahib intervened, “Who are you to claim the body? We have arranged

for the burial at the nearby graveyard. Go away”.

The Punditji, who had been till then silent, objected to

this and informed the crowd about Kallu’s affiliation to the Hindu faith. “For

the last several years, he had been paying obeisance to gods and goddesses

outside Hanuman temple.” This infuriated Maulvi Sahib’s companions. “Don’t make

a fuss of it. Think of the poor child,” intervened the doctor. The dreaded

doctor played a trick and urged the crowd to allow Gudia to take a decision

about her father’s last rites.

People in the crowd, now divided into groups, were each

putting claims on the corpse. Soon the atmosphere turned tensed, leading to an

altercation before the police arrived there to take control of the situation.

The police carefully listened to the religious heads and then to the little

wretch. Meanwhile, one of the policemen came to Gudia and then asked her name.

He went on to take further details to get a clue of her

religion.

“What is your father’s name?”

“Kallu,” answered Gudia.

“What is your mother’s name?”

“Don’t know”.

“Where do you live?”

“On the street.”

“Has your father left anything for you?”

Gudia handed him the big clothe-bag, the only asset her

father left for her. The policeman emptied the bag in a huff but found nothing

there to drive any conclusion from the items — a bruised aluminum bowl, a

crumpled skull-cap and a saffron sheet printed with swastikas stuffed were all

there was. Clueless, the policemen sat

for a while in silence then asked Gudia “How you want your father’s last rites

to be performed?”

The crowd fell silent. Now it was Gudia’s turn to speak. Her

decision would be final and binding for everybody there. Was she so

important? Had she ever dreamt of this?

No. She had never hoped for much from people, except one man but he was dead

now. She was the daughter of a roadside beggar whose life centred on the

two-kilometre stretch from Lal Jain Mandir to Fatehpuri Jama Masjid.

She knew her father was a liar, a master impersonator who

would change his looks, his language and expressions according to the places of

worship he visited, according to people he begged to. But she was being given

much importance today. For a moment she felt like a princess standing at the

centre of her subjects begging for mercy, waiting for her announcement.

Unaware of the significance of her decision, she paid a

glance to her father whose hollow black cheeks gleamed in the morning rays. She

heard herself murmuring “Ah! How important you have become after your death. If

you could see those who abused you; those who rebuked you; those who shrugged

you off, are desperately thinking about your welfare! At least you will now

live in peace! Did you not often abuse these dignified men? Indeed, you were an

ungrateful man.” But she would not be ungrateful. She must move to the doctor

before the rays reflecting off the imposing glass-structure building nearby

became pricklier.

Anguished over her decision, the Maulvi angrily said,

“Haven’t you sold your father for the sake of a few coins? You are truly the

daughter of an imposter.”

The writer is chief sub editor, The Statesman, New Delhi

Advertisement