Archery World Cup : Indian men’s recurve team wins gold . Deepika Kumari bags silver

India also clinched the mixed team recurve bronze as Ankita Bhakat and Dhiraj finished the meet with eight medals - five gold, two silvers and one bronze.

Tagore reminded Noguchi that every military action was unique and indefensibly justified. Tagore admitted many failings of human civilization but he also insisted that in society a moral dimension would always manifest itself. Rejecting Noguchi‘s contention that Japan was attempting to bring a new order in the Asian context, Tagore called the Japanese action ‘manslaughter‘

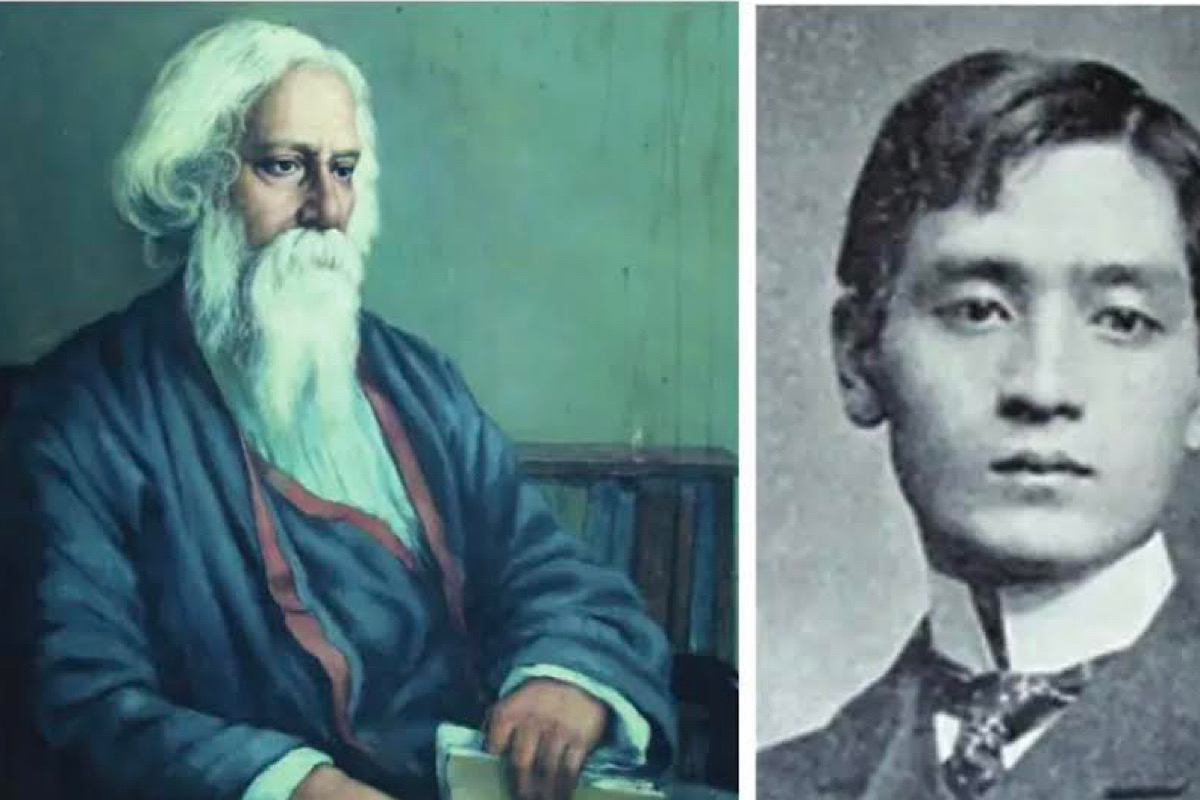

Tagore and Noguchi (photo:SNS)

Yonjiro Noguchi (1875- 1947)’s first letter to Tagore in 1938 began recalling his visit to Shanti Niketan in 1935. He wrote another long letter to Gandhi. He referred to Tagore’s vehement criticisms of Italy’s adventurism in Abyssinia and asked the poet whether he felt the same about Japanese aggression in China.

He clarified that he agreed earlier with his criticism of Italian aggression in Abyssinia. He alluded to Tagore’s visit to Japan in 1916 and his appreciation of Japan’s attempts to modernize, and shunning westernization.

He justified Japanese aggression in China as part of Japan’s plan for building Asian unity. He pointed out that Tagore’s error was his failure to comprehend that the aggression in China was not for conquest but to unseat the Kuomintang government for its misdeeds and its inability to stop foreign exploitation.

Advertisement

Tagore in his reply expressed his profound surprise at the content of the letter and at the very outset stated that “neither its temper nor its contents harmonize with the spirit of Japan”. He observed that the “passion of collective militarism” helplessly overwhelmed even the creative artist like Noguchi.

He found it paradoxical that Noguchi still shared his condemnation of the Italian massacre in Ethiopia but refused to condemn a similar aggression of Japan in China.

This meant that there was neither any consistency nor any principle as “Japan is infringing every moral principle on which civilization is based”.

Taking a dig at Noguchi’s claim that it was an unprecedented and unique situation, Tagore reminded him that every military action was unique and indefensibly justified.

Tagore admitted many failings of human civilization but he also insisted that in society a moral dimension would always manifest itself. Rejecting Noguchi’s contention that Japan was attempting to bring a new order in the Asian context, Tagore called the Japanese action ‘manslaughter’.

He reminded Noguchi that when he criticized westernization in his lectures in Japan, he carefully distinguished between “rapacious imperialism” of the West and the East, preaching and practicing the path of perfection preached by Buddha and Christ. In a frontal attack, he stated that Noguchi’s enunciation of the doctrine of ‘Asia for Asians’ was an instrument of political blackmail.

It had all the “virtues of the lesser Europe which I repudiate and nothing of the larger humanity that makes one across the barriers of political labels and divisions”. Tagore was also amused at the statement of a Japanese politician that Japan’s military alliance with other European powers, Germany and Italy was only for moral and spiritual reasons without any materialistic concern.

He pointed out “In the West, even in the critical days of war-madness, there is never any dearth of great spirits who can raise their voice above the din battles and defy their own war mongers in the name of humanity”.

Tagore reminded Noguchi that even with immense suffering yet such voices “never betrayed the conscience of their people which they represented”. He was sure that similar voices existed in Japan.

Only that they were muzzled. Support of inhumanness was only propaganda “which has been reduced to a fine art”. He said voices of dissent in nondemocratic nations were suppressed by draconian means. He reminded Noguchi, if the Japanese people really knew about the horrendous acts that were taking place in China, they would not support it at all.

There could not be a disjunction between an “artist’s function” and “his moral conscience”. In a frontal attack on the warlords, he predicted that the inevitable loss that Japan was destined to suffer would be more than China’s sufferings. He also declared undauntingly that “China is unconquerable”.

He added “China is holding her own no temporary defeats can ever crush her fully aroused spirit”. It had “an inherently superior moral stature”. He reminded Noguchi that another great Japanese thinker, Okakura, was always conscious of China’s greatness.

Pointing out the brutal destruction of China by Japan, Tagore quoted from an article of Madame Chiang, Soong Mei-ling (1897-2003) of the irreparable damage that the Japanese perpetrated by destroying and maiming thousands of people and even China’s civilizational treasures.

But with his optimism he also reminded Noguchi about the transient nature of the present crisis. He ended his letter with an assertion that a “true Asian humanity will be born” and “poets will raise their song and be unashamed, one believes, to declare their faith again in a human destiny which cannot admit of a scientific mass production of fratricide”.

Again, paying back Noguchi in the same coin he said he would release his letter to the press. Noguchi knew very well that his letter to Tagore, if released to the press, would draw wide publicity.

Tagore understood the game and released his rebuttal to the press. Noguchi responded with another letter praising Tagore for his eloquence. He agreed with Tagore about the greatness of Chinese civilization and admitted that conquest of China would be impossible.

The Japanese objective was a limited one, merely removal of Chiang and asserted that Okakura, if alive, would have supported it. He even argued that the popular view in Japan was seldom published in the West while the Chinese were excellent propagandists.

Noguchi cleverly attempted to distinguish a corrupt leadership from a mass of pure people, to justify the Japanese aggression and occupation. The Japanese army was a liberator.

He repeated the claim of the beginning of a new age in Asia that he made in his first letter as well. He contended that militarism was a fact in both Japan and China and both needed to be condemned.

He accused Tagore of being partial towards China. Noguchi claimed that Japanese militarism, unlike the West, had a moral context. Stating that the prevailing circumstances were exceptional it had to be defended as Japan was dedicated “on the great work of reconstructing Asia in the new way”.

He even suggested that Tagore could be the peacemaker by writing to Chiang. In an oblique manner he even accused Tagore to “willfully blacken Japan to alienate her from your country”.

Tagore’s reply began with a dig at Noguchi for having published the letter to him in the Amrita Baazar Patrika adding that “it makes the meaning of your letter to me clearer”. Noguchi described Tagore’s letter as disappointing and partisan. In his reply Tagore was severe and blamed Noguchi for his belief “in the infallible right of Japan to bully other Asiatic nations with your Government’s policy which is not shared by me”.

He added significantly “my faith that patriotism which claims the right to bring to the altar of its country the sacrifice of other people’s rights and happiness will endanger rather than strengthen the foundation of any great civilization, is sneered at by you as the quintessence of a spiritual vagabond”.

Tagore dismissed the entire argument as false and misleading and compared it with Napoleon’s march to Moscow. He dismissed Noguchi’s argument of a future new Asia and said that the brutal action in China would never build lasting goodwill.

He dismissed Noguchi’s claim of Chinese being excellent propagandists stating that the Japanese excelled equally in such acts. He also castigated him for wrongly depicting Indian heritage.

Tagore added that he was pained by the Japanese brutal action and that Japan no longer remained a shining example for him. He unequivocally supported the Chinese for resisting the Japanese aggression which he mentioned in response to an invitation from a Japanese friend to visit Japan.

He ended the letter passionately but clearly by “wishing you people whom I love, not success, but remorse”.

(The writer is a retired Professor of Political Science, University of Delhi)

Advertisement