Bhagat Singh’s kin expresses outrage over behind-bars portrait of Kejriwal

Expressing his outrage, Sandhu said an attempt has been made to compare Kejriwal with the legends.

Whether Gandhi tried to persuade the then Viceroy Lord Irwin with full sincerity of purpose to commute the death sentence is a matter of debate till today, but what is not so debated is the fact that in our history textbooks the role of armed revolutionaries in the freedom struggle is not given due recognition.

It is a relatively lesser known fact today that the day the firebrand revolutionary in India’s freedom struggle Bhagat Singh was hanged, thousands of households from Lahore to Kanyakumari went hungry. People were grief-stricken, stunned and distraught at the sheer insensitivity of the British rulers in hanging the iconic youth of India’s freedom movement. At the same time they also lamented the fact that Gandhiji, the leading Congress leader of the day, did not do his bit to save the lives of not only Bhagat Singh, but also Rajguru and Sukhdev from the gallows.

Whether Gandhi tried to persuade the then Viceroy Lord Irwin with full sincerity of purpose to commute the death sentence is a matter of debate till today, but what is not so debated is the fact that in our history textbooks the role of armed revolutionaries in the freedom struggle is not given due recognition. Historians have appeared reluctant to think beyond the one-sided non-violence narrative while assessing and analysing India’s struggle to get rid of the British rule in the country.

Since Independence, countrymen have been fed only one viewpoint through history books, educational curriculum and hearsay, whereas many other individuals, ideas and organisations, in spite of their tremendous and truly inspiring roles in achieving freedom, have been overlooked. The stellar contributions of Netaji Subhash Chandra Bose, Rashbehari Bose, Chandrashekhar Azad and countless others have been blissfully forgotten by our famous historians and curriculum makers; attempts have been made to present revolutionaries as terrorists in school textbooks, and gigantic events like the Mutiny of 1857 and the Naval Revolt of 1946 have been presented either in a lesser light or through distorted optics.

Advertisement

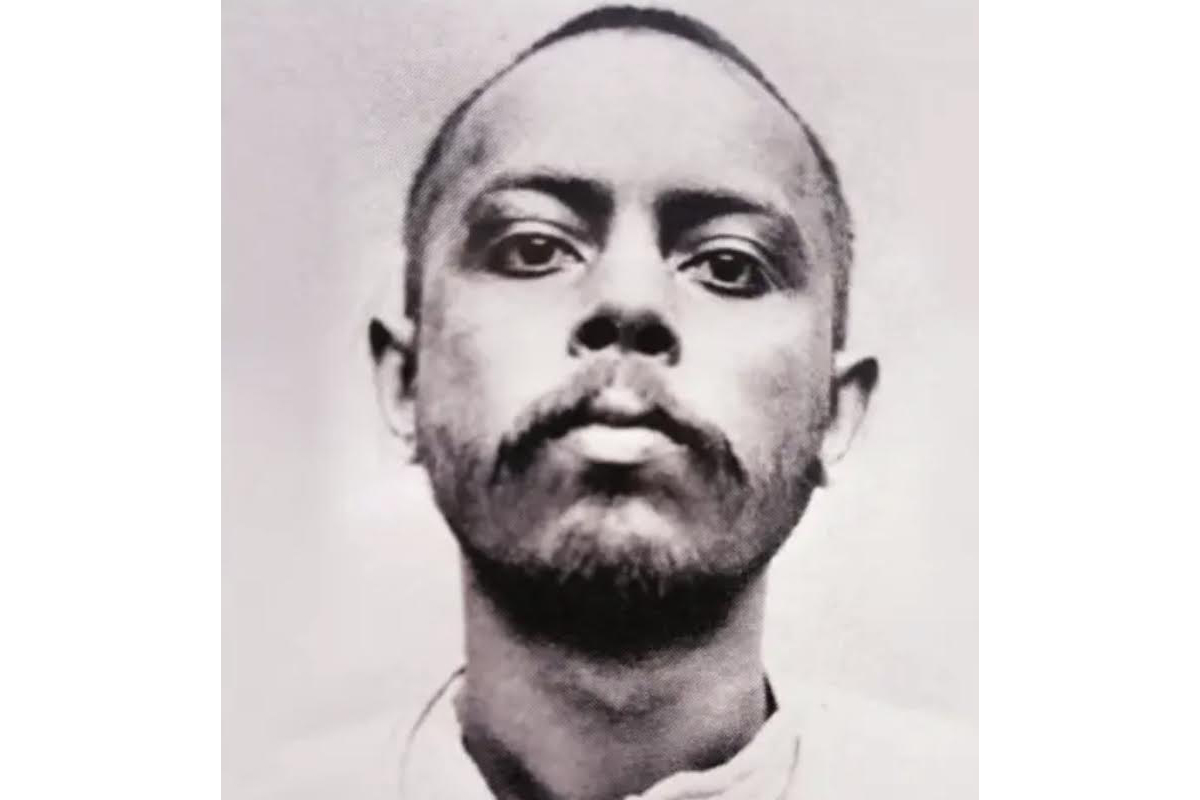

Consequently, many martyrs and their crucial roles have been thrust into mere footnotes, deliberately deleted or edited to keep the focus solely on the key figures of the manufactured narrative. Yet it is hard to completely wipe out legends, icons and heroes from the nation’s collective consciousness. They live on in public memory and folklore. One such unsung hero was Ullaskar Dutta. The saga of Ullaskar Dutta (1885- 1965) is one that is part of the neglected narrative of gunpowder and gumption. He is among those brave young Bengalis who chose the path of armed resistance to end British rule. Dutta was a revolutionary associated with Anushilan Samiti and Jugantar, and was a close associate of Aurobindo Ghosh’s brother Barindra Nath Ghosh. He had expertise in bomb-making. When the British police arrested members of the Jugantar Party like Khudiram Bose and Barin Ghosh, Ullaskar was also arrested for being involved in the Alipore Bomb case where an attempt was made to kill the ruthless British magistrate Douglas Kingsford. He was sentenced to death by hanging in 1909, but later the death sentence was reduced on appeal and he was deported to Cellular Jail for life.

Ullaskar survived the excruciating tortures of the jail authorities and he lived till 1965. Ullaskar has been in the news recently as his sesquicentennial ancestral house in Bangladesh is at last going to be free from encroachments. The Sheikh Hasina government has taken an admirable step by deciding to preserve the residence of Ullaskar Dutta at Brahmanbaria since this house in Kalikachha village has historical significance as a witness to his life and work. For many months prior to the government declaration, a number of human chains were organised in front of Ullaskar’s birthplace and prominent Bangladeshi nationals, organisations and media outlets had been vocal in demanding action to evict encroachers and declare the building as a heritage house.

But people’s remembrance of the revolutionary has not been restricted merely to his birthplace. Every year the Ullaskar Dutta Academy, a research group, based in Kolkata, solemnly observes 16 April, Dutta’s birthday, with an objective not just to pay homage to the fiery revolutionary, but to remember, read, discuss and re-discover the forgotten legacy of armed revolutionaries who shook the mighty foundations of the British Empire. All this shows the passion, love and respect people still cherish for Ullaskar in Bangladesh and in West Bengal. Ullaskar’s profile is truly amazing. He hailed from an affluent Baidya family in the village of Kalikachha in present-day Bangladesh. His father Dwijadas Duttagupta was a member of the Brahmo Samaj and had a degree in agriculture from London University.

Ullaskar was a meritorious student and had a great passion for Chemistry, but he could not complete his studies at Presidency College, Calcutta because he was rusticated from the college for hitting his British professor Russell who made derogatory remarks about Bengalis. It was a time when the British did not respect any member of the Indian community and could speak contemptuously of Indians without any fear of being prosecuted. Ullaskar could not stomach such insults. At that time, many young Indians were inspired by Bipin Chandra Pal and began to join the Swadeshi Movement in large numbers. Ullaskar was no exception. He gave up his foreign clothes and adopted traditional Bengali attire. Dutta joined Anushilan Samiti in 1908 and later the Jugantar group and acquired knowledge in bomb-making.

Khudiram Bose used a bomb made by Ullaskar and Hemchandra Kanungo to kill the magistrate Kingsford. Earlier, a bomb made by Dutta was used to kill Andrew Fraser, the then Lieutenant Governor of Bengal. Ullaskar was awarded a death sentence. Though unwilling initially to sign an appeal against the order, he later filed it on the advice of fellow revolutionaries like Barin Ghosh and his own parents. When Ullaskar was sent to Cellular Jail, he was subjected to torture and is said to have lost his mental balance. He was transferred to the island’s lunatic ward at Haddo, and held in an asylum for 14 years. In 1920, when the British authorities set him free, Ullaskar came to Calcutta. But he was again arrested in 1931 and sent to jail for 18 months. After Independence, Ullaskar went to his birthplace and married the widowed daughter of Bipin Pal. He breathed his last at Silchar on 17 May, 1965. In his book Amar Karajiban (My Prison Life), Ullaskar chronicled the horrible days of his jail life and the barbarities inflicted by British police on prison inmates. In the Cellular Jail, prisoners, instead of bullocks, were yoked to the handle of the turning wheel of the oil-mill for crushing oil from coconut and sesame.

And they had to run round the oil-mill unremittingly from morning to evening with a brief interval for a bath and morning meal. If anybody was found relaxing at any point of time, he would be bludgeoned. Ullaskar was once asked to glean three litres of oil in a day. He refused on the ground that even oxen could glean not more than two litres a day. Angered by his refusal, the prison keepers fettered his arms raised to the ceiling and feet to the ground. He stood motionless for three days. When they untied him finally, he collapsed senseless. He went insane when he woke up.

Not only that, he was also given electric shocks in his semi-conscious state and as a result, as Ullaskar recollected in his book, “every nerve, fibre and muscle in the body seemed to be torn by it.” An account of his prison life is also found in the books written by Savarkar and Barin Ghosh. Matching his name, Ullaskar was a fun-loving person who was praised for his optimistic vision even by the trial judge. He had an intellectual bent of mind and in the jail he would often make his fellow inmates forget about their pain and desolation by telling them jokes and lighter verses.

It is sad to see that today’s generation knows so little about Ullaskar Dutta. No study or narrative of the freedom struggle can be called authentic or comprehensive if it, deliberately or inadvertently, excludes, negates or neglects the contributions of Ullaskar and countless other revolutionaries who staked their lives in search of freedom from the colonial masters.

(The writer, a Ph D in English and a freelance writer, teaches English at the Governmentsponsored Sailendra Sircar Vidyalaya, Shyambazar, Kolkata.)

Advertisement