Declare dry day and holiday in educational institutions on 22 January: Yogi

Terming this special occasion as a 'national festival', the Chief Minister said that liquor shops should be kept closed in the state on January 22.

Alternate modes of instruction under the common misnomer of ‘blended learning‘, are beginning to lose steam and effectiveness largely due to paucity of innovation, appropriate strategising, lack of instruction delivery models in the blended mode, redundant and repetitive applications, and shaky internet platforms

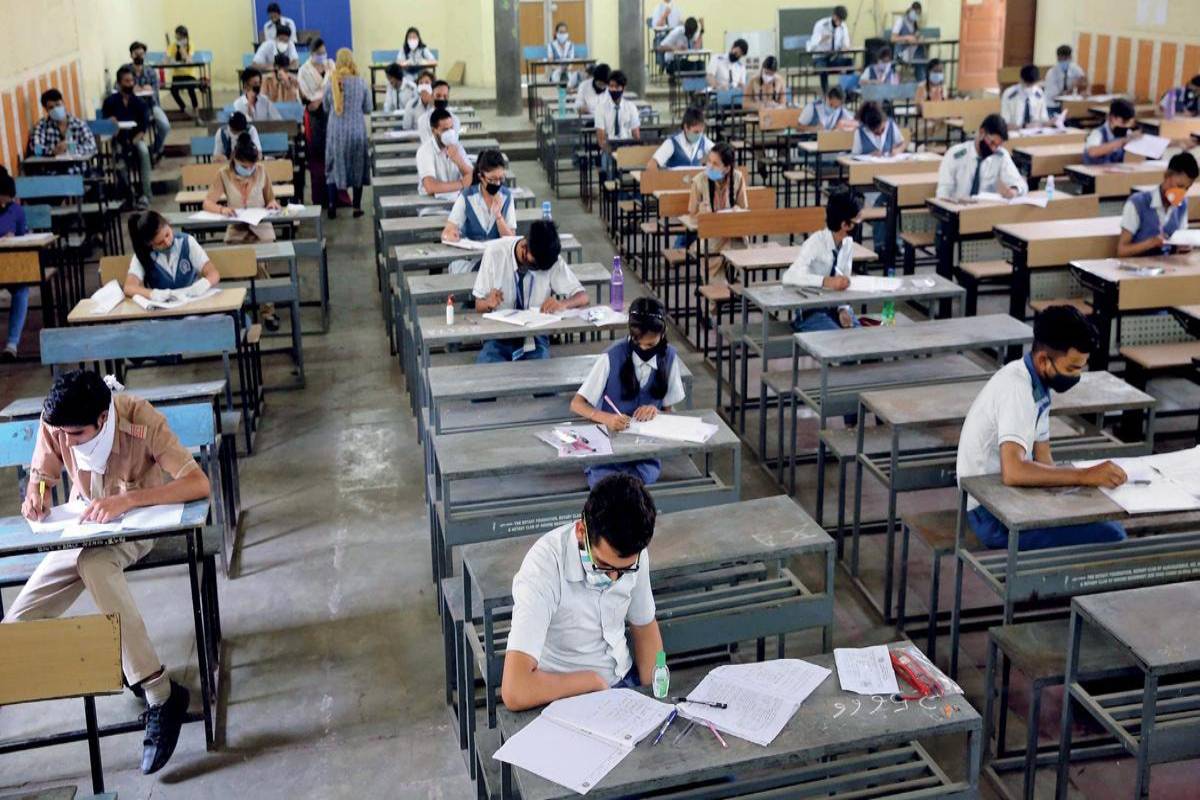

Resuming institutional education post-Covid has been one of the most contested topics in policymaking circles the world over. The predominating concern is to strike the right timing between ensuring the physical well-being and safety of the stakeholders, primarily the students and the teachers, and the imperative to bring down the damage to education to a manageable minimum. With a hiatus of nearly 18 months between the universal closure of educational institutions and the present time, the chorus to open educational institutions and resume instruction in the physical, face-to-face mode has justifiably grown louder.

Again, initial reports of resurgence of infection in institutions that experimented with an early resumption of physical teaching reveal that the threat of a surge in infections post resumption of offline instruction is real and immediate, largely because the premise of physical distancing and Covid protocols in educational institutions are an impossibility.

The argument in favour of early opening of institutions as a comparison to resumption of most other group activities in daily life is partially flawed since the comparison overlooks the fact that institutions, including classrooms, are the only places where participants are required to stay in a generally enclosed space for a continuous stretch of 5-6 hours every day with poor ventilation and overcrowded spaces.

Also, the fact that children and adolescents are still without the protection of vaccination is a consideration too serious to overlook, since Covid data across the world clearly suggests that while the intensity of infection in children might be comparatively less vis-à-vis adults, the threat of severely negative outcomes for Covid-infected children are not negligible because an overwhelming number of our children do not go through routine physiological testing to detect hidden co-morbidities which may define severity of infection, multi-organ failures or even death.

At the same time, the damage for education is too serious to overlook given that around 1.6 billion children have been forced out of institutions and estimates suggest that around 40 per cent of them may not be able to return due to severity of financial conditions post-Covid, lack of resources, compulsion to work to supplement family incomes, or worse, because of being orphaned by the disease.

While there has been a general acceptance of alternate modes of instruction based on the internet and use of mobile devices, platforms and applications the world over, to lessen the impact of disruption in education, these modes of instruction and evaluation, under the common misnomer of ‘blended learning’, are beginning to lose steam and effectiveness largely due to paucity of innovation, appropriate strategising, lack of instruction delivery models in the blended mode, redundant and repetitive applications and shaky internet platforms.

While ‘blended learning’ is a complicated instruction delivery model requiring proper community-level calibration of steps, practices and training, it has been virtually reduced to a simplistic two step model of using an online platform for conducting largely one-way instructional delivery through a video-conferencing application and a home-based open book examination where the internet is used merely to transfer copied ‘answers’ to a centrally located nodal evaluation centre.

The ‘blended learning’ in practice in most places is merely a skeletal model designed to exhibit curricular continuity rather than effective instruction and evaluation. The usual experience of the stakeholders in this alternative practice is that the ‘blended learning’ in practice has begun to lose steam and is already eroding the interest of students in genuine learning. It is more a chore rather than a creative teaching-learning pursuit. One of the reasons the chorus to re-open institutions in the physical mode has grown louder is the realization that ‘blended learning’ which began as an alternative mode of instruction has turned into an ineffectual and lackadaisical practice in the last year and a half.

Such considerations make the decision to time opening of educational institutions enormously tricky. While there may not be a universally effective formula meant to dictate when physical learning should resume, it is worthwhile to plan and design a viable, objective framework for reopening of institutions.

This is so because the decision to resume physical learning ought to avoid the twin hazards of yielding to emotional demands which lack objective rigour and initiating a resumption of learning in the physical mode without adopting remedial paradigms to offset the disruption the pandemic has caused to the student community.

In other words, apart from considerations of health and safety of children on the campus, policy planning to rehabilitate disadvantaged students who might have missed out on attaining the required skill sets in the last year and a half, is a primary requirement for a rational opening of institutions.

A mechanical resumption which does not factor in the damage to learning that has inevitably occurred to billions of students shall continue the skill attainment disparity witnessed in the pandemic and shall cripple such learners for years to come. The case of Sierra Leone, a west African country which once faced the Ebola epidemic crisis in 2014 forcing the closure of educational institutions for over three years, can serve as a case in point where resumption of physical learning was made not only after the country overcame the virus in 2016 but also after an alternative instructional paradigm to mitigate the learning disability caused due to closure of institutions was adopted and put in place.

To put it succinctly, resumption of face-to-face learning ought to be a nuanced and objective call since the virus is sure to remain with us for at least a couple of years before it loses its damaging potential.

As such, three predominant considerations ought to drive our timing to resume physical instructions in our institutions. The first obvious consideration is the ability of institutions to offer safe hygienic conditions to all stakeholders including children. The second factor should be the availability of educational planners and the teaching community to drive institutional and instructional changes through the adoption of remediation instruction and accelerated learning strategies.

The third and most important of the three is the adoption of community co-ordination and communication to build trust among parents and guardians to assure them of the safety of children within the institutional premises since considerations of the fear of infection may still influence many parents to keep their children out of physical learning.

Institutional closures have worsened educational inequalities the world over and have jeopardized the potential of billions of students to attain desired skill sets at the end of their education. It is imperative that the anticipation of institutional reopening is supported by a viable remediation strategy in instruction that can ensure a holistic scaffold for billions of vulnerable learners.

Advertisement