Congress, allies sabotaged Jammu’s national projects: Dr Jitendra Singh

The minister further alleged that the Congress also denied 4% reservation to the people living along the International Border in this region.

Since Nehru was anointed by Gandhi in 1946, a great deal of democratic water has flowed under the bridge. Several commoners have been Prime Ministers since and yet the Nehru family has not modified its old royal ways. The party presidentship is bouncing like a shuttlecock between the mother and son.

(SNS)

The more people, especially politicians, criticize the Congress party for being dynastic, the more unreasonable they are. Little do they realize that there appears to be a conviction amongst the members of the leading family that they have a divine right to rule India. It began in 1946 when the party needed to elect a new president. Maulana Abul Kalam Azad had been the head for six years in a row, largely due to the Quit India movement and most of the leaders being in jail.

Moreover, by 1946 Independence was in the air with the Labour Party in power in Britain. As per the standard practice, the party secretariat asked the 16 Pradesh Congress Committees (PCC) for their preference of the candidate. One PCC voted for Archarya J.B. Kripalani while the rest 15 supported Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel. The All India Committee was to then elect the President formally. Gandhi intervened and asked the Sardar to step aside and let Jawaharlal be the President.

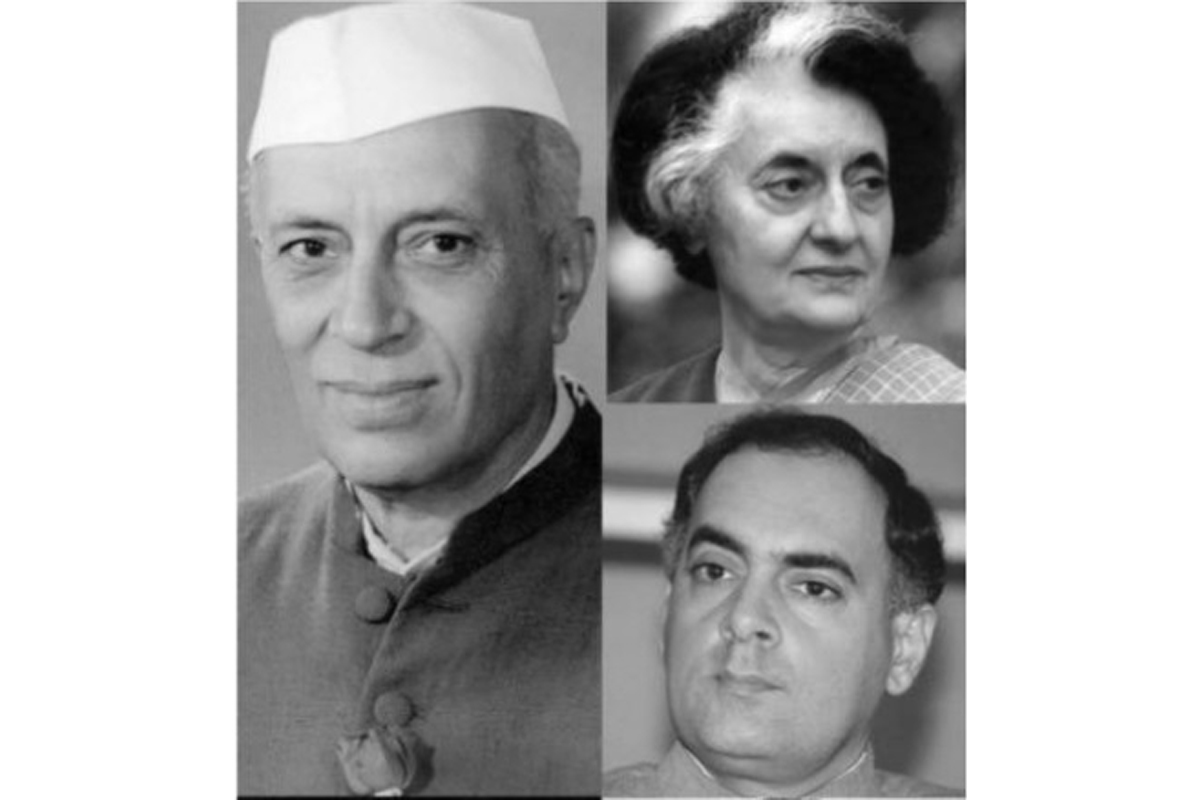

Patel obeyed and Gandhi asked the 21-member Working Committee of the party to select Nehru. In 1946, presidency was important because its incumbent would head any central government that is formed thereafter. So did Nehru; first as Vice-President of the Interim Government under the Viceroy as President. On 15 August 1947, Jawaharlal Nehru was automatically chosen the Prime Minister. So specially selected and anointed by the Father of the Nation as he was called, was a unique honour and a rarer gesture. It would give anyone the message that he was a divine preference.

Advertisement

Not only Nehru but even his progeny would remember the blessing. Especially if one recollects that in his lifetime MK Gandhi was beginning to be considered by some as the tenth avatar of Vishnu. Few doubted that Nehru wanted his daughter Indira to succeed him. K Kamaraj, the president of the Congress Party, possibly knew of Nehru’s wish. But 1964 was the time when political life was restrained by decorum and leaders did not behave as uninhibitedly as they do now. Kamaraj did not allow an open election by the parliamentary party but held a secret survey of the Lok Sabha members as to who was their choice. According to the survey, the majority favoured Lal Bahadur Shastri in preference to Morarji Desai.

The difference between the secret survey and an open election was doubt in place of transparency. People in Gujarat and elsewhere also suspected that perhaps Kamaraj had chosen a weak and relatively colourless candidate. When the 1967 general elections came he could perhaps be persuaded to step aside in favour of Indira Gandhi who presumably would be a more attractive leader electorally. Thus no one would point a finger at Nehru for having nominated his daughter as his successor. A gap of 16 months between the father’s demise and the daughter’s succession respected decorum which now one would not have. This inhibition was abandoned when Indira Gandhi was assassinated in October 1984.

A dozen or more bullets were pumped into her delicate body.A ccording to informal reports inside the AIIMS hospital, she was brought dead. By 11 a.m., the BBC radio news had reported her death. But Akashvani repeated the shooting report but not death until a few minutes before 6 p.m. although Rajiv Gandhi had returned in early afternoon from Kalaikunda military airport; he happened to be on a visit to West Bengal. But Rashtrapati Giani Zail Singh was away in West Asia and by the time he could return it was a little before 6 p.m. at which time Rajiv was sworn in as Prime Minister.

This was constitutionally an irregular way of electing a PM. When Nehru died, promptly Gulzarilal Nanda, the seniormost in the cabinet was sworn in as an interim incumbent until the new candidate was duly elected by the Lok Sabha parliamentary party, as indeed Shastri was. Shastri died at Tashkent and Indira Gandhi was duly elected by the parliamentary party. It was only then that Nanda, who had again been the interim PM, stepped aside. The same procedure should have been followed after Indira’s demise. The two senior cabinet ministers were Narasimha Rao and Pranab Mukherjee; either could have been interim PM until the formal election of the ongoing PM, in this case, Rajiv Gandhi.

Earlier his brother Sanjay Gandhi was reputed to behave as Indira’s crown prince of the old eras. He held no elected or appointed position in 1974 and was therefore, an extra-constitutional entity. Yet he exercised autocratic powers at least in Delhi. In September 1974, his wife Maneka complained to him that one Devi Prasad Tewari, a Students Federation (CPM) activist at Jawaharlal Nehru University had prevented her from attending classes as there was a strike. Like a chivalrous husband, Sanjay phoned P.S. Bhinder, the number two police officer of Delhi to look into the matter.

Bhinder, in mufti dress, rushed to JNU and caught hold of the first student he saw in the department concerned and dragged him to Sudipto Ghosh (IAS) Additional District Magistrate’s office and had him locked up. Soon he was sent to Tihar Jail. All the while the victim protested that he was not Tewari and that he was Prabir Purkayastha who had nothing to do with the SFI. Ghosh knew Prabir as he had undertaken to registermarry him with Ashoka Lata before long. But since Sanjay Gandhi had instructed Bhinder, Ghosh behaved as if he was doing his duty. This was long before the imposition of the Emergency. In a democracy such autocratic behaviour was unthinkable; only a monarchy could tolerate such caprice. Subsequently, to prevent Ashoka Lata meeting her fiancé at Tihar, Prabir was transferred to Agra.

To send him away farther away, he was later sent to Naini Jail. What was visible through this unfortunate episode was the readiness with which senior educated officers were prepared to toe the line, no matter how whimsical the desires of the princes. When the Allahabad High Court unseated Indira Gandhi from the Lok Sabha in early June 1975, she declared an internal Emergency and went on to abolish the rights of citizens given by the Constitution. Or else, how could the divine right to rule be perpetuated? In contrast, when Atal Behari Vajpayee government fell by one vote in 1999, he promptly resigned and sought re-election.

That one vote was ethically questionable because Giridhar Gomango, a Lok Sabha member, had become chief minister of Orissa and was governing the state. Yet he sneaked into the Lok Sabha and voted. When the Emergency came, Sanjay Gandhi expressed noble sentiments for the country. He appealed to the people to talk less and work more, he wanted to clean up and smarten cities as well as to control the exploding population. He was told that Muslims particularly have more children than others. He however did not know that the Hadith, also an Islamic scripture, prohibits birth control except through coitus interruptus.

So Sanjay nominated Rukhsana Sultana (Hindu name Meenu Bimbet), a fashionable lady of Delhi, to persuade the Muslims of Shahjehanabad to plan their families as well as to transfer to allotted plots in trans-Jamuna and vacate their illegal quarters near the Turkoman Gate and surroundings. Sultana made Dujana House her headquarters which was facilitated with nasbandi operations on both men and women. Inevitably, mayhem followed with teargas, firing and resultant deaths on quite a scale. Since Nehru was anointed by Gandhi in 1946, a great deal of democratic water has flowed under the bridge. Several commoners have been Prime Ministers since and yet the Nehru family has not modified its old royal ways. The party presidentship is bouncing like a shuttlecock between the mother and son.

(The writer is an author, thinker and a former Member of Parliament)

Advertisement