For the past few years we have been constantly hearing the phrase ‘demographic dividend’ in the speeches and utterances of our political leaders. It is almost as if this is the magic wand which will address all our chronic problems and take us to the promised land of bliss.

For those of us brought up with the notion that population explosion or overpopulation is the root cause of all our ills, this may seem to be rather ironical. How come the most serious stumbling block to all our developmental efforts in the past half century and admittedly our abject failure to control the Malthusian growth of population is suddenly being flaunted as our valuable asset? We need to take a close look at the population data and analyse the facts and figures in the light of prevailing socio-economic realities. The idea is to ascertain if the runaway growth of population has in reality been to our advantage.

As per the census of 2011, children in the 0-14 age group consist of around 35 per cent of the total population of India. In absolute numbers, this comes to around 36 crore ~, more than the current US population of 32.5 crore. As regards China, the most populated country in the world, the 0-14 age-group of the population is 23.49 crore or 17.1 per cent of the total Chinese population. In terms of the young, we definitely have an edge over the developed countries which have an ageing population with higher percentage of middle aged and the older.

In point of fact, this is only a reflection of the demographic transition that we are passing through at present with medium fertility and birth rates and lower death rates. As both birth and death rates decline, we are expected to attain a stable population by around 2050 when the share of the 0-14 age group will decline steadily and the percentage of the middle-aged and the old will rise consistently.

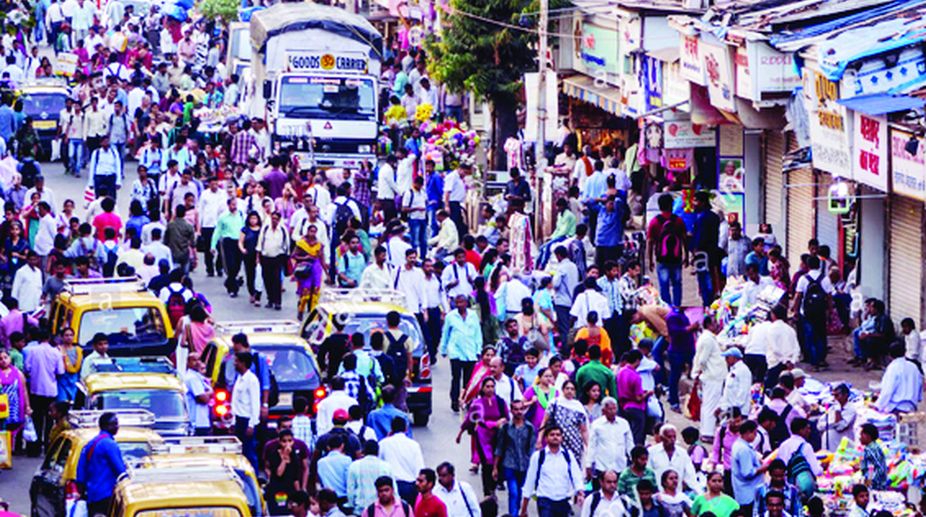

Already the fourth round of the National Family Health Survey (NFHS 4) conducted in 2015-16 indicates that the below-15 population has declined to 28 per cent compared to 34.9 in NFHS 3 conducted during 2005-06. At the same time it is true that for the next 20/30 years India will continue to enjoy this advantage of having the highest number of young working population in the world. But are we really prepared to put this transitional advantage to its best use for constructive development or is this a demographic time-bomb silently waiting to explode when millions of poorly educated, unskilled, frustrated and angry young men and women attain the working age and demand their share of the cake. But before that it is important to examine the conditions under which the majority of children grow up, conditions which are vital inputs for their future well-being and conduct as adult citizens.

As per the latest Sample Registration Survey (SRS) data released by the Registrar-General of India, 34 children out of every 1000 “live births” die before they reach their first birthday. This means that every year about seven lakh children below the age of one are lost. These deaths are to a large extent due to malnutrition, poor living conditions and lack of primary healthcare. According to a survey conducted by the office of the Registrar-General, the major reasons of neonatal deaths are premature births, low-birth weight, neonatal infections, pneumonia and diarrhoeal diseases.

These factors point to sordid living conditions under which the majority of future citizens are born and brought up in our country. The National Health Mission started by the previous UPA Government had fixed a target to reduce the IMR to 25 per 1000 live births by 2012, but as per data till 2016 that goal still remains a distant dream. Even the Under 5 Mortality Rate (U5MR) is very high compared to other developing countries. As per NFHS 4, it is 50 per 1000 live-births with rural areas reporting such deaths at 56.

Compared to this, the world average released by UNICEF is 40.8. Even among our neighbouring countries the rate is much lower. In case of Bangladesh, it is 34.2, Bhutan 32.4, China 9.9, Nepal 34.5 and Sri Lanka 9.4. Only Pakistan has a higher U5MR at 78.8. If nothing else the data on IMR and U5MR should put our overworked politicians busy with electoral calculations and its religious ramifications to shame.

Proper medical care and attention to the nutritional needs of the growing children is another area where are record is abysmal. As per NFHS-4, 38 per cent of Indian children under the age of five suffer from stunted growth due to under-nutrition which has serious repercussions for their future health.

Another 36 per cent of the under-5 children have lower weight corresponding to their age. Instead of boasting the demographic advantage we should ask ourselves as to what the country can expect from the future citizens when 74 per cent of the children grow up poorly fed, undernourished and underweight. According to a recent World Bank report prevalence of underweight children in India is the highest in the world and is double that of sub-Saharan Africa. The report observes that this has very serious consequences for mobility, mortality, productivity and economic growth in India. There is also a severe problem of anaemia among children between 6-59 months as 58.4 per cent of them are anaemic.

This is perhaps quite natural as NFHS 4 reports that 50.3 per cent of women in the child bearing age of 15-49 are anaemic. Poverty and ever-rising costs of essential food items are depriving expectant mothers as well as their newborn children of the means to obtain the minimum required intake for a balanced diet. The Global Hunger Index, 2017 ranks India as 97th among 118 countries with a very serious “hunger situation”.

Our claim to be one of the fastest growing economies in the world sounds quite hollow in the light of this child nutrition scenario. Hungry and undernourished, many with stunted growth, the majority of Indian children therefore grow up with natural resentment and hatred for the society that has denied their rightful claim to live with reasonable comfort and adequate sustenance. Such resentment is often reflected in the increasing violence and explosion of anger both in domestic as well as public life with scant regard for social norms or civilized behaviour that we witness in India today. The situation is further complicated by cynical exploitation of such resentment by the so-called democratic polity in India to suit the narrow selfish goals of unprincipled political leaders.

If on the other hand we look at the children from the growing urban based middle and upper income families the problem takes another dimension. There is no dearth of nourishing food here; rather it is a question of plenty. Though no reliable data on child obesity; it has been estimated through a sample survey in 2010 that 19.3 per cent of the Indian children are obese. This data roughly corresponds with NFHS 4 which reported that 20.7 per cent of the Indian women and 18.6 per cent of men in the 15-49 age are overweight or obese. Thus though we have majority of children with stunted growth or in undernourished condition we also have substantial prevalence of obese and overweight children.

The situation is equally dismal either way. The small family norms with one or two children have created a generation of pampered and self-centred boys and girls among these households with no sense of responsibility or attachment towards the society that has brought them up. Reports of increasing juvenile crimes that we now see in the newspapers almost daily are perhaps reflections of the living conditions which a child passes through to adolescence be it in poor or low income households or in an affluent family.

(To be concluded)

The writer is retired Principal Secretary, Govt of West Bengal