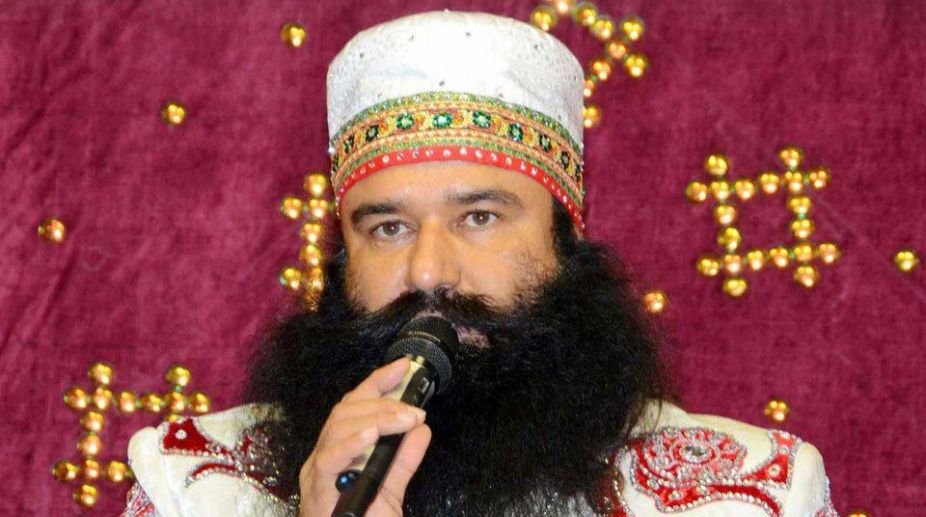

Dera Sacha Sauda chief Gurmeet Ram Rahim out on 40-day parole

Notably, the Dera chief was also granted parole ahead of the Haryana panchayat election and Adampur Assembly bypoll. Rahim was granted parole for a month on June 17.

Gurmeet Ram Rahim Singh (Photo: Facebook)

A frustrated judge in an English (adversarial) court finally asked a barrister after witnesses had produced conflicting accounts, ‘Am I never to hear the truth?’ ‘No, my lord, merely the evidence’, replied counsel.

Peter Murphy’s illustration about the adversarial justice delivery system is 100 per cent true when we discuss the Indian justice delivery system. The ongoing uproar on conviction of Baba Ram Rahim is the result of a 15-year long trial by a specialised court that is meant to be speedier than ordinary courts. When the first time idea of a special court was introduced, it was resisted on the ground that it was against rule of law.

The Apex Court in Anwar Ali Case and Kathi Ranning Rawat Case upheld special courts on the ground that they were based on doctrine of reasonable classification i.e. there may be certain offences whose trial requires priority over the rest and when this is intended they should be tried more speedily than other offences.

Advertisement

It would require in certain respects a departure from the procedure prescribed for the general class of offences. However, speedy administration of justice, especially in the field of the law of crimes is a necessary characteristic of every civilized Government and there is not much point in stating that there is a class of offences that require such speedy trial. The trial of Ram Rahim once again validates the insistent crisis in the Indian criminal justice system.

The accusations against Gurmeet Ram Rahim were made by a Dera Sadhvi (2002) by writing an anonymous letter to then Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee. The letter also alleged that accused Gurmeet was involved in sexual exploitation of many female followers inside the Dera. The Punjab and Haryana High Court took suo motu cognizance of the Sadhvi’s letter and directed the Central Bureau Investigation (CBI) to register a case against the Dera chief (2002). The CBI filed the charge sheet in 2007 and the trial commenced in 2008.

It took nine years to come to the conclusion that Ram Rahim was guilty. Ram Rahim is also facing trial in two separate murder cases. One is of Dera follower Ranjit Singh in July 2002 and the second of journalist Ram Chander Chattrapati in October 2002. He has under our constitutional system the ‘right to appeal’ and many forums are still to be exhausted before final conviction. If this is the state of affairs in a specialised criminal court then we need to seriously think about our adversarial justice delivery system.

The adversarial system of justice administration was espoused in common law countries. It relies mainly on the skills of the advocates representing their client’s positions rather than on some neutral party, usually the judge, trying to ascertain the truth of the case.

Such judges decide often when called upon by counsel rather than of their own motion what evidence is to be admitted when there is a dispute. In the adversarial model, the parties are responsible for initiating and conducting the litigation. In addition, the parties bear primary responsibility for determining the sequence and manner in which evidence is to be presented and legal issues are to be argued.

The underlying principle of the adversarial system is “innocentuntil-proved-guilty.” Adversarial system is also sometimes characterised by high costs, delays, contributing to a regime of plea bargaining, uncertainty of law, lawyer-dominated approach and lack of parity of powers between the two parties to the litigation.

The natural consequence of this mode is that justice is like any other commodity to be purchased only by those who can afford its cost. Formal not effective access to justice and formal not effective equality is all that is sought. To deliver speedy criminal justice, it is indispensable to have a timebound mechanism for hearing, arguing and deciding, including appeals.

A law can be enacted prescribing an upper limit of time by which a criminal case has to be finally decided. This could be a maximum of six months or one year depending upon the complexity of the crime. All stakeholders – namely the accused, police, lawyers, witnesses, judges at various levels – have got to become accountable for finalising the case before the prescribed time-limit.

For any deviation from the limit, they must assign reasons for non-compliance in writing. Another issue which crops up frequently is that of witnesses turning hostile. They declare the truth at the commencement of the case and later give opposite evidence in the court or they refuse to attend the court. This arises either due to the fear of the accused and the police or due to inducements of different types.

A strict mechanism has to be evolved for preventing the witness turning hostile. The Malimath Committee gave its apprehensive consideration to the question whether this system is satisfactory or whether we should consider recommending any other system. The Committee as an alternative studied in particular the inquisitorial system followed in France, Germany and other Continental countries. The inquisitorial system is undeniably effective in the sense that the investigation is supervised by the judicial magistrate which results in a high rate of conviction. However, the Committee on equilibrium realised that a fair trial and in particular, fairness to the accused, are better protected in the adversarial system.

However, the Committee felt that some of the good features of the Inquisitorial System can be adopted to strengthen the Adversarial System and to make it more operative and efficient. This includes the duty of the Court to search for the truth, to assign a proactive role to the judges to give directions to the investigating officers and prosecution agencies and leading evidence with the object of seeking the truth and focusing on justice to victims.

But these suggestions were ignored by the government. What is at stake here is not judges, the judiciary or governance, but the very process of human and economic capital-building and accumulation – to meet India’s international commitment at the UN and to achieve the millennial goals through sustainable development.

The incessant denial of parity of power and helplessness to pause politico-criminal nexus erodes the very constitutional idea of India – an India whose courts ought to deliver justice within a reasonable time, estimated by the normal human life cycle.

(The writer is Associate Professor of Law, National Law University of Odisha.)

Advertisement