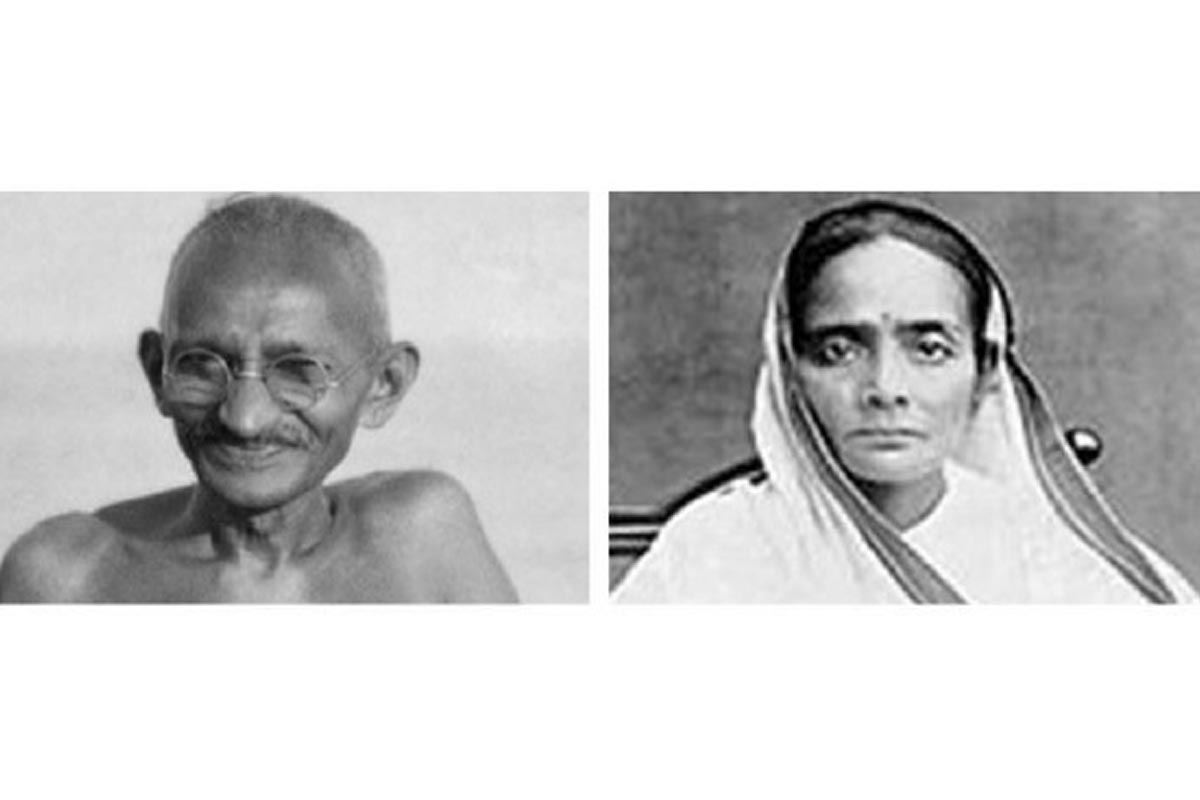

Bhamini Oza joins ‘Gandhi’ series as Kasturba Gandhi

Actor Pratik Gandhi's wife, Bhamini Oza, to portray Kasturba Gandhi in the upcoming 'Gandhi' series, adding a touch of authenticity and personal connection to the iconic roles.

Gandhi’s autobiography also reveals the strength hidden in that soft and self-effacing façade that Kasturba projected so effectively in later years. And the magnitude of her achievement is yet to be accorded the recognition it deserves. To walk in the shadow of a world figure and still retain one’s sense of self is no mean feat.

(SNS)

The 22nd of February marks the 76th death anniversary of Kasturba Gandhi. She passed into eternity while serving her prison term at Aga Khan Palace in Pune. The year 2019-20 also marked the 150th birth anniversary of ‘Ba’ but unfortunately she did not get the attention of the nation, that she deserved. It has been said that behind every great man there is a woman. In the case of Mahatma Gandhi, by his own admission it was his wife Kasturba. Way back in the early 1920s, the world had heard of a son and a husband who poured his heart out in the pages of his autobiography, which he called The Story of My Experiments with Truth.

It was regarded as one of the most outstanding books of all times. It is replete with a women-friendly spirit that softens the stark realities of gender relations in our society. In his writings and outpourings, Gandhi transcends the boundaries, which hide the private from public and emerges as the foremost name in the small list of those illustrious and sensitive men of the 20th century who have spontaneously empathized with the women’s cause. Gandhi has acknowledged the debt of his mother, wife and the black women in South Africa and the Suffragette struggle of British women in 1906-07 as influences on the evolution of his concept of Satyagraha for which he is revered across the world.

The attitude of respect and the understanding of women’s problems that he exhibited later in life was derived from his mother and wife. This helped him in his perception of women as equal partners at home and in society and not merely as mothers and wives but as nation-builders too. Writing about his mother, he states: “The outstanding impression my mother has left on my memory is that of saintliness” . It was to his mother that Gandhi owed a passion for nursing. She was also the moving force behind his technique of appealing to the heart through self-suffering.

Advertisement

Years later Gandhi acknowledged his debt to his mother. While in Yervada jail he told his secretarycompanion Mahadev Desai. “If you notice any purity in me, I have inherited it from my mother and not from my father”. A keen observer Gandhi could not miss out on how both his mother and wife quietly resisted their exploitation in the conservative mid-19th century Gujarati household. He learnt the method of Satyagraha from them and made good use of this weapon in his fight against exploitation by the British as part of a major strategy to humble their might. Gandhi made his inner sentiments public in an age when such confessions were frowned upon.

Kasturba entered his life at a very tender and impressionable age. Through the pages of his autobiography, we get to know the blossoming of a teenaged girl into a woman with a ‘mind of her own’. While putting up with an “obstinate” and “tyrant” of a husband, tenders him with love and care and earned his admiration and appreciation. Neither of them realized when and how their private and public concerns converged at a point from where they both set out on a journey which would only take them on to the highest level of conjugal love which is the preserve of only the enlightened few. In his autobiography”, Kasturba first appears as an adolescent bride to whom he is passionately attached. In his later life he is ashamed for this attachment.

And his considerable contribution to the emancipation of women which became part of the Indian Constructive Programme for the regeneration of our nation even as freedom struggle was in progress, could be traced to his own adolescent attitude to women. Gandhi’s autobiography also reveals the strength hidden in that soft and self-effacing façade that Kasturba projected so effectively in later years. And the magnitude of her achievement is yet to be accorded the recognition it deserves. To walk in the shadow of a world figure and still retain one’s sense of self is no mean feat.

As wife of the Mahatma, Kasturba accomplished this, not through overt rebellion and intransigence, but through her long-drawn resistance to allowing her will to be bent to that of her illustrious husband. Gandhi is said to have admitted to John S Hoyland that he learnt the lesson of non-violence from Kasturba when he tried to bend her to his will. “Her determined submission to my will on the one hand and her quiet submission to suffering my stupidity involved on the other, ultimately made me ashamed of myself and cured me of my stupidity in thinking that I was born to rule over her; and in the end she became my teacher in non-violence”.

If she ultimately acquiesced in Gandhi’s ideals and endeavours, it was only after careful appraisal and self-examination. And if Gandhi proved, in the initial years of marriage, to fit the stereotype of a “tyrannical” husband, during the 1930s and after, he looked up to Kasturba as a strong life-partner, without whose constant support, his mission would have been left unaccomplished. An important frame in Gandhi’s autobiography is the picture of Kasturba as bewildered and unable to comprehend the change that was going over this barrister so much dressed like European and living a similar life with a governess, for his children.

He now changes his style of living, dispenses with servants, engages himself in public activities, undertakes protests, suffers police brutality but does not retaliate, goes to jail and has all sorts of similar reformist visitors, hospitality which taxes Kasturba’s fortitude and health. At one point where the reformist husband forces her to clean the toilet of his visitor, Kasturba says enough is enough. A violent conflict between the two followed. The quarrel reached its peak with Gandhi asking his wife to quit. Then she retaliates and a repentant Mahatma goes over the entire gamut of man-woman relationship. He sees his conduct as wrong, which leads him to think of the general condition of women, the subordinate position to which women are forced in Indian society.

It is here that we find changes in the attitude of men towards women. The incident provides a reformist impulse as strong as the ejection from a first class compartment of a train in South Africa had done. His recollection of these events in his book is no superbole, it is factual, almost devoid of emotions. At the end of this incident when the Mahatma was almost was on the verge of pushing Kasturba out, she shook him to his core by her words. He describes this incident thus: “The tears were running down her cheeks in torrents and she cried. Have you no sense of shame? Must you so far forget yourself? Where am I to go? I have no parents or relatives here to harbour me. Being your wife, you think I must put up with your cuffs and kicks? For heaven’s sake behave yourself, and shut the gate. Let us not be found making scenes like this! I put on a brave face, but was really ashamed and shut the gate. If my wife could not leave me, neither could I leave her. We have had numerous bickerings, but the end has always been peace between us. The wife, with her matchless power of endurance, tolerance has always been the victor”.

The Mahatma himself terms this recollection as “sacred” thus revealing how much he values the same. This episode is the second most important incident in the journey of MK Gandhi towards Mahatmahood. The first was the incident that took place on Mauritzberg Railway platform on 7 June 1893, where the young Gandhi was pushed out of the First Class coach of the train he was travelling in. Both these events happened on the sacred soil of South Africa and had a profound impact on Gandhi. Thus was born a Satyagrahi who fought against all forms of prejudice and injustice till his last breath. Gandhi’s recognition of separate and independent dimensions of women was the hal-mark of the feminism that he espoused. He appreciated the compulsions of independence and a separate entity in a woman. These traits embedded in a woman must be legitimized was what he always, stressed upon. It was an article of faith with Gandhi that only from this legitimization, a woman’s graduation into the obligational and functional aspects of life can be a fair and just dispensation.

(To be concluded)

(The writer is a Former Director, Gandhi Smriti and Darshan Samiti, New Delhi)

Advertisement