Mughlai food still tickles the palate

Mughalai food has surprisingly survived long after the end of the Mughal empire, started by Zahiruddin Babar in 1526. The…

Though what passes off as Mughlai food these days is not the stuff that the great Mughals ate, it nevertheless continues a tradition of several centuries, during which a large assortment of dishes have been added

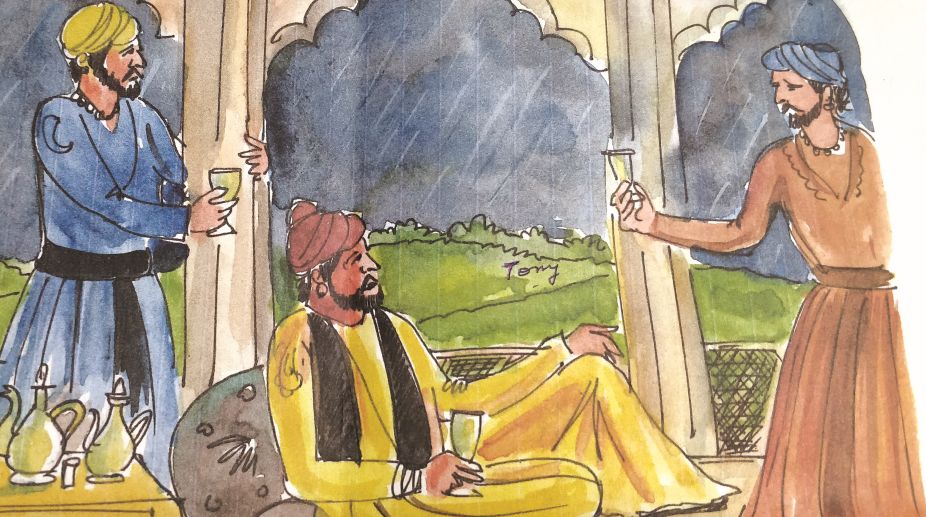

Before dinner: A sundowner

Mughlai food has a history of over 500 years of delicious dishes. When Babur came to India, he was fascinated by the country’s cuisine and the large variety of spices available.

Hitherto he was used to eating log-cooked chicken and meat, specially the “raan” or hind leg of the ram. In India he began to improvise dishes. His son Humayun did the same and Mughlai food started being prepared in the royal kitchen.

Akbar improvised further after his widespread conquests. More varieties were available because of the addition of goat’s meat, hardly available in countries like Persia and Afghanistan.

Advertisement

Akbar was a frugal eater and preferred to eat alone. But his son Jahangir was fond of eating and drinking. Noor Jehan took command of the empire and took decisions on all important matters of State. The emperor seemed to enjoy it as he found more time for indulging in lavish feasts.

More and more dishes were added to the Mughal Dastarkhuan, or meal spread. However, it was not as though he had taken leave of State matters and allowed the kingdom to be run only by the queen.

The verse he coined in her honour was a bit of an exaggeration, though there is no doubt that he was a gourmandizer. Even so, he was quite concerned about governance and sometimes he would overrule his beloved consort.

What Jahangir did was bettered by Shahjahan, the greatest of the Mughals in pomp and show. His menu was an enlargement on that devised by his father and grandfather. In this he was aided by his daughters, Jahanara and Roshanara, after the death of his chief queen, Mumtaz Mahal, who otherwise used to order the royal dishes to be served each day.

Instructions would be given in the Agra Fort (the Red Fort came up after her demise) to the Mir Bakawal and passed on to the Khansamah and further to the assistant Bawarchi or cook. The daughters later took her place, helped by the heir apparent Dara Shikon.

His brothers, Shah Shuja and Murad were also great connoisseurs of food, but Aurangzeb was spartan in his habits, which were also reflected in the meals he ate. He told a visiting hakim from Turkey that Mughal cuisine combined the pleasure of heaven and hell, since it was delicious and pungent at the same time.

Though what passes off as Mughlai food these days is not the stuff that the great Mughals ate, it nevertheless continues a tradition of several centuries, during which a large assortment of dishes have been added.

It was during the reign of Jahandar Shah (1712) that Mughlai food went out of the confines of the Red Fort for he had married a dancing girl of the Walled City, Lal Kunwar, whose relations and friends all came to know of Mughlai recipes. That was five years after the death of Aurangzeb, who had popularized Delhi non- vegetarian food in the Deccan.

Mohammad Shah Rangila, the courful emperor (1719-48) was a great food connoisseur, who improvised probably more than all the earlier Mughals. Even his modest meals were fit for kings and princes.

After Mohammad Shah, Ahmad Shah and then Shah Alam kept up the tradition but they were no great connoisseurs. Akbar Shah II, who succeeded Shah Alam, did not have control of the whole country, which had come under the British and his meals reflected his reduced status.

His son, Bahadur Shah Zafar, the last of the Mughal emperors, was fond of deer meat as he had been fond of hunting in his younger days, but he also liked lighter food, particularly moong-ki-daal, which came to be known as Badshah Pasand, while Malka masoor was named after Queen Victoria.

The Mughlai eaten in the Red Fort was mostly roasted stuff. Tandoori Murgh (they did not like the hen!) served as the main course, Murgh Mussalam for those in need of an elixir, roasted “raan”, mince of several kinds, roghan josh, pasanda, kofta nargisi, liver, heart of lamb, memna or lamb’s haunches, korma, kababs of many kinds, including the chappali kababs, bhuna gosht, full roasted ram, fish curries, fried river fish and exotic salads, all washed down with wines from Portugal and Spain, especially the wine of Oporto, in the case of those Mughals who drank (not all did).

A great delicacy was venison and the flesh of a number of birds like duck, partridge, pigeons and bater, chidi pilao from sparrows, kaaz kulang and other birds, including the migratory ones, eaten with naan, sheermal with chappati (they didn’t call it roomali roti).

Desserts comprised fruit and sweets, halwas and kheers. The prince in charge of food distribution to the royal inmates was known as Mirza Chappati during the “mutiny” days, though his real name was Mirza Fakru.

Now, besides the five star hotels, Mughlai food has been popularised by Karim’s and others, including such outlets as Al Kausar, which serves preparations with secret recipes left behind by Nabbu Mian of the late 19th century.

Jamma Masjid, Ballimaran, Mehrauli, Nizamuddin and Bara Hindu Rao are among the places with favourite food joints and so Mughlai food continues to tickle the taste buds even in the 21st century.

A slice of the past

According to noted food connoisseur, Sadia Dehlvi:

“Little is known about Delhi’s food culture before the arrival of the Delhi sultans in the 12th century. These sultans belonged to warrior clans of Central Asia, where food was more about survival than sophistication. The refinement in their cuisine came through interactions with local Indian communities and the abundance of fruits, vegetables and spices available here.

The tables of Qutubuddin Aibak, Iltutmish and Razia Sultan consisted of meat dishes, dairy products, fresh fruits and varieties of local vegetables. “The 14th century poet and historian Amir Khusrau wrote of the tables of Sultan Muhammad bin Tughlaq, which consisted of about 200 dishes.

The royal kitchen fed about 20,000 people daily. In his famous Persian Mathnawi Qiran us Sa’dain, the epic poem that later came to be known as Mathnavi dar Sifat-e-Dehli for its glorification of Delhi’s culture, Khusrau writes, ‘The royal feast included sharbet labgir, naan-e-tanuri, sambusak, pulao and halwa. They drank wine and ate tambul after dinner.’

“In the Travels of Ibn Battuta in Asia and Africa, translated by Gibb, Ibn Battuta describes a royal meal at the table of the early 14th century Sultan Ghiyasuddin at Tughlaqabad as a lavish spread comprising ‘thin round bread cakes; large slabs of sheep mutton; round dough cakes made with ghee and stuffed with almond paste and honey; meat cooked with onions and ginger; sambusak that were triangular pasties made of hashed meat with almonds, walnuts, pistachios, onions and spices placed inside a piece of thin bread fried in ghee, much like the samosa of today; rice with chicken topping; sweet cakes and sweetmeat for dessert.’

“Ibn Battuta mentions sharbet of rose water that was served before meals, which ended with paan. He writes of mangoes, pickled green ginger and peppers; jackfruit and barki, a yellow gourd with sweet pods and kernels; sweet oranges; wheat, chickpeas, lentils and rice.

“The arrival of the Mughals in the 16th century added aroma and colour to Delhi’s culinary range. Although Babur, the founder of the Mughal dynasty, had little time for Indian food. In Baburnama, his memoirs, the emperor complains about the lack muskmelons, grapes and other fruits plentiful in his Afghan homeland.

Babur’s son and successor Emperor Humayun is credited with bringing refined Persian influences to Delhi’s cuisine. This resulted from his years spent in Persia after having been defeated by Sher Shah Suri. The fusion of India and Persian styles of cooking came to be known as ‘Mughal cuisine’.

“In Ain-i-Akhbari, Abul Fazal, Emperor Akbar’s courtier, mentions that cooks from Persia and various parts of India were part of the that cooks from Persia and various parts of India were part of the royal kitchen.

This led to the merging of Turkish, Afghan, Indian and Persian ways of cooking. Fazal chronicles that more than 400 cooks from Persia formed the large kitchen establishment that had head cooks, official tasters and numerous administrative departments.

“A kitchen orchard and garden supplied fresh vegetables and fruits such as lemons, pomegranates, plums and melons. During the rule of Emperor Shah Jahan in the 17th century, the Mughal Empire reached its zenith.

Red chillies were brought to India by the Portuguese, who began its cultivation in Goa during the 16th century. Two hundred years later, red chillies made their way to Delhi and were greatly used during the reign of Bahadur Shah Zafar.

“During the time of Emperor Muhammed Shah Rangeela in the 18th century, the city canal’s water became polluted. The royal hakims advised the citizens of Delhi to eat chillies to help purge toxins from the body. This eventually led to the inclusion of red chillies in Delhi’s food and the tradition continues.”

R V Smith

Advertisement