ADB report paints disconsolate picture of Pakistan’s economy

With the current dire state of the crippling economy, Pakistan has now become the most expensive country with the highest living cost in the whole of Asia.

An ageing crisis has taken root in several Asian countries, shedding light on the need for better healthcare facilities for the elderly as well as the implementation of policies to counter elder abuse and abandonment.

Asia is facing an impending ageing crisis, wherein the population of younger people is decreasing and that of the elderly is rising. This has had several economic and social implications, and it is imperative for countries, like China, Japan and even India, to develop high-quality healthcare facilities for elderly people. But first, it is vital to understand why populations are ageing.

Meena Ganesh, CEO, Portea Medical, says there are a number of reasons for this surge, such as the common practice for people in their 20s and 30s to focus on their careers and financial stability, especially in the middle and lower-middle income groups.

This has contributed to a decline in birth rates and thus, in the percentage of the younger population. Another factor is that a drastic improvement in healthcare facilities has led to a much higher life expectancy rate compared to, say, 20 years ago, Ganesh added.

Advertisement

Previously implemented policies by countries to limit their populations are also responsible for ageing populations.

China’s (in)famous “one family, one child” policy, which was implemented in 1979 to contain population growth, seems to have backfired — leading to a low proportion of youngsters to take care of their ageing parents and grandparents. India, compared to China or Japan, is a much younger country; however, there still seems to be a burgeoning population of senior citizens, Ganesh asserted, adding that the conventional healthcare system in India is inadequate to cater to patients who suffer from non-critical illnesses and chronic diseases.

This is where “at-home” services come into play. Portea has been providing at-home healthcare facilities for elderly people in India since 2013.

It has created a framework which involves employing “caregivers who maintain a safe environment at the patient’s home and handle health-related issues, like personal hygiene of the patient, overall sanitation, noise controletal,” Ganesh said.

However, most sections of Indian society don’t seem open to the idea of athome care just yet. One of the biggest challenges in this regard is the “societal mindset which associates a stigma to bedridden family members being attended to by outsiders instead of family members,” Ganesh said, adding that such a stigma detrimentally affects the well-being of patients and deprives them of much-needed professional care.

Moreover, elderly care is a multipronged approach; while some sections of society are able to afford at-home healthcare, a massive proportion is not due to financial limitations.

However, according to Ganesh, when one looks at the long-term cost of care for elderly people suffering from chronic diseases or long-term illnesses, the overall cost usually turns out to be lower than a normal “in-hospital” treatment.

Also, professional medical care provided in the patient’s home environment often helps them heal faster and better and enjoy a better quality of life, she explained. Another problem that has plagued Indian society for years is elder abuse and abandonment. Abuse, in this regard, can take many forms, such as physical and verbal assault, torture, mental agony and economic exploitation, like ridding elders of property rights forcefully.

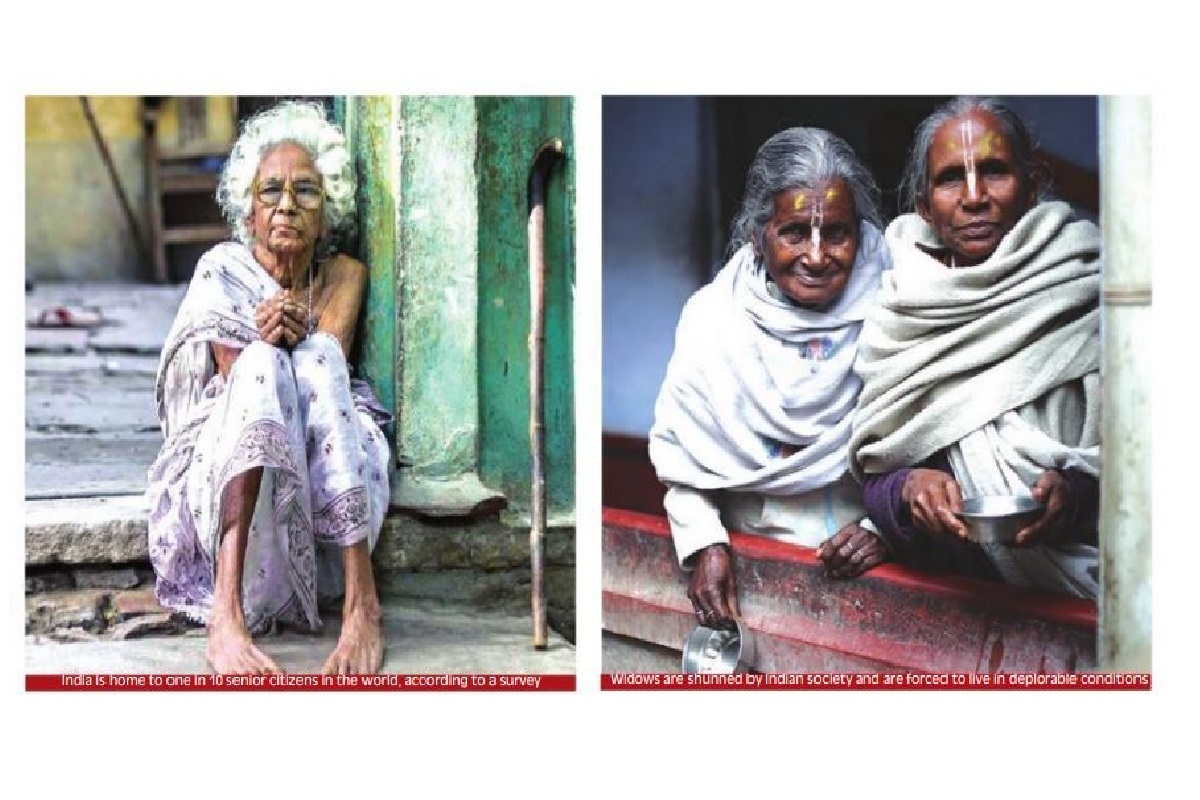

It is pertinent to mention here that aged widows are one of the most oppressed and destitute sections in India who are shunned from their families and from society and are forced to live in beggarly and pitiful conditions.

Such instances of ostracisation will only tend to proliferate as populations grow older, unless measures are taken to counter them.

Thus, the government has a massive role to play in this area. India is home to one out of every 10 senior citizens in the world. A survey conducted by HelpAge India found that half of the elderly people that they surveyed (including 48 per cent men and 52 per cent women) reported that they had suffered abuse. Such exploitation is carried out because, after a certain age, elders are considered unproductive, dependant on others and, most importantly, a liability. What is a matter of grave concern is that most elderly people in India are not even aware about their rights and about laws implemented to protect them, like the Maintenance and Welfare of Parents and Senior Citizens Act 2007, for instance.

The government is taking measures, yes, but more must be done — in the form of awareness programmes and speedy trials to create a secure atmosphere for elders, free from the fear of abandonment and abuse.

The importance of civil society cannot possibly be overstated in this regard: a large number of NGOs has acted as a saving grace for thousands of abandoned and abused senior citizens in the country.

This year’s budget has announced a layout of Rs 9,000 crore for elderly care. What remains to be seen, however, is how these funds will be utilised.

Some positive steps have been taken to counter elder abuse in India in recent times, like amendments to the Maintenance and Welfare of Parents and Senior Citizens Act 2007 — providing for an increase in the jail term for those who abuse or abandon their aged parents from three months to six.

However, as is often the case in India, there lies a wide lacuna between enactment and actual implementation of laws. What is needed most of all is a change in people’s mindset, a mindset nurtured by love and morality, not imprisoned by hate and greed.

Advertisement