West Bromwich Albion chiefs sacked

English football club West Bromwich Albion on Tuesday sacked their chairman John Williams and chief executive Martin Goodman. The changes…

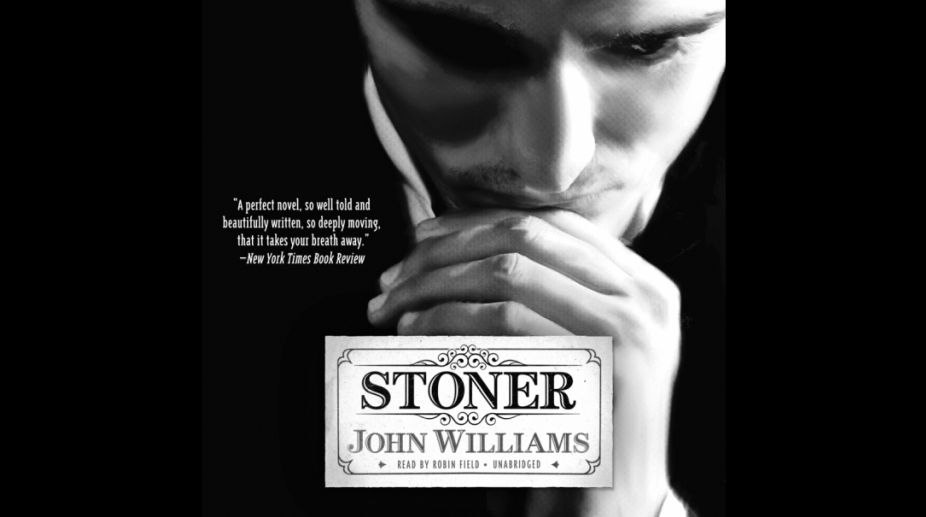

Not since Rohinton Mistry’s A Fine Balance have I read a book as moving as Stoner. Written by John Williams, it was published in 1965 and sank without attracting much critical notice at the time. Only in recent years has it surged in popularity thanks to fervent advocacy by the French writer Anna Gavalda and the news that it is being turned into a film starring Casey Affleck. Since then, the novel has sold phenomenally well all over the world, riding on a wave of fulsome endorsements from a slew of famous writers. What can explain its sudden bestseller status?

Let me begin by saying that Stoner is literally unputdownable, if I allow myself liberal use of a cliché. The book is in the tradition of university or academic stories, popularly known as “campus” novels, similar to works by Malcolm Bradbury and David Lodge, or Mary McCarthy’s The Groves of Academe, Phillip Roth’s The Human Stain and The Dying Animal and JM Coetzee’s Disgrace. However, unlike Bradbury’s and Lodge’s books that focus on academic exchanges and tend to satirise academic life, Stoner is deeply serious.

The story centres on the life and times of William Stoner, a peasant boy who joins the University of Missouri as a student in 1910 and dies as an assistant professor of English literature shortly after being forced to resign in 1956 on grounds of poor health. His life is distinctly unremarkable and large parts of it are barely known to his students, as the novel’s opening makes it affectingly plain. In between studentship and professorship, William marries badly, lives a miserable domestic life with much whining and whingeing, suffers professional reverses arising from departmental rivalries, forms a few deep friendships and has a brief, yet life-expanding love affair with a young lecturer.

Advertisement

William meets Edith, a banker’s daughter, at a party and immediately proposes. Their marriage, however, is loveless and passionless. A one-time consummation results in the birth of his daughter; the remainder of his domestic life is desolate, moving up and down with the moods of his wife. This life does light up, briefly, when William falls in love with a much younger colleague at his university, but the relationship comes to an end when the head of William’s department, Professor Lomax, threatens to expose the affair. The long-standing feud between William and Lomax creates more complications in the protagonist’s life and resurrects at key moments in his career to knock him back to his miserable situation, denying him any possibility of happiness.

This is the story in broad brushstrokes. However, beyond these outlines, the relentless focus is on the anatomy of William’s character formation and his navigation through his chosen academic path with a phlegmatic temperament. His life is a series of misfortunes. As for the helpless characters in A Fine Balance, one secretly prays William’s endless misfortunes will end somehow, somewhere. The question is, are his troubles of his own making or is he helpless against forces greater than him? Unlike the characters in A Fine Balance who cannot fend for themselves in the face of hostile and larger forces, William is comparatively better placed and considerably empowered to change the course of events. It seems he chooses not to. His phlegmatic reaction to the hard blows shows a fatalist streak in him, similar to the characters in works by Thomas Hardy. Many reviewers have called Stoner sad and bleak, but from the viewpoint of the main character, sadness and a phlegmatic temperament is inscribed deeply in the biography of his family.

The clue to this lies in William’s early years at the farm looked after by his hardscrabble mother and father. His father is a taciturn man, deeply wedded to his land and its daily routine, and William’s early years are marked by backbreaking farm-work endured in silence. This unvoiced acceptance of whatever comes his way, while keeping his emotions in check, stays with him throughout his life and shapes his reactions to all the rough and the smooth — mostly rough — that comes his way.

What struck me most in Stoner was the theme of silence. It reminded me of Colm Toibin’s recent book, Nora Webster, where silence and grief are major themes. The searing effects of silence and grief following the death of Nora’s husband are painted with heartbreaking honesty. Silence also becomes a defining feature of William’s life, and this prevents us from breaking through to his inner person.

The turnaround in his fortunes occurs when his father arranges to send him to an agricultural college to learn modern farming methods with a view to improving his family farm. Midway through his course, William suddenly shifts to studying English literature. He is encouraged by Sloane Archer, a lecturer at the university. William excels at his new subject and ends up joining the faculty after finishing his PhD. At the university, his only close friendships are with Fisher and Dave, two young academics on an early career path like himself.

This is the only occasion in the novel when we get somewhat closer to the protagonist’s inner thoughts. However, when the short-lived fraternity fractures with Dave’s death in World War I, from thence onwards William’s life again becomes a riddle shrouded in mystery.

The only reference to historical times is mention of the two World Wars, with the addition of a nod to the Great Depression, which has caused the fortunes of William’s father-in-law to sink. As for the wars, the effect on William is that in the first he loses his close friend, in the second he loses his son-in-law. Beyond personal effects, the university-wide effects are the haemorrhage of the staff to war efforts and an increased workload on those who choose to stay back instead of joining the ranks.

William’s emotional and psychological universe can be fully discerned through his key relationships. The one with his parents is emotionally detached. Nothing happens, verbally or non-verbally, between the family. There is a grim sense of some duty to be performed, lands to be tilled and the vagaries of nature to be obeyed uncomplainingly. This shapes him psychologically, making him pliable, emotionally closed and self-contained, developing traits that feed into his marital and professional relations with unpleasant consequences.

In the relationship with his wife, he fails to connect. Edith is a straitlaced girl with no wide exposure of the world to lead her own life. In his effort to compensate for his emotional detachment, William showers attention on his daughter and Edith reacts by estranging him from his child.

Stoner is a novel that endures because of its universality. The themes of academia as a life-altering event for a peasant boy destined for rural life, the silence and emotional restraint, an obsessive concern with career and the constant struggle to be or not be in human relationships make William an oddly loveable character in the wider world of factional politics and chaotic domestic life. Through it all he holds fast to his academic position as the most meaningful way to live. In the process, normality is exiled to the suburbs of his personal priorities.

William is a classic study in character formation that pans out as being single-minded rather than well-rounded. The micro-effects of being single-minded are universally illustrated in loveless marriages and broken families, and that will ensure the longevity of the book.

The writer is a journalist and essayist whose work has appeared in national and international publications

Dawn/ ANN

Advertisement