As the title of the book suggests, this volume is a collection of plays from South Asia, which deal with the social and political performance of Islam in the region after 1947. It distinguishes between Islam as faith and Islam as political ideology; however connected the two might be in the constantly evolving narrative of jihad at home and abroad. The first of its kind, the anthology puts together six play-texts from Bangladesh, India and Pakistan, which offer insights into a situation where the performance of political Islam refers to both the constructions about the myths about the religion, and their deconstruction through a variety of theatrical modes.

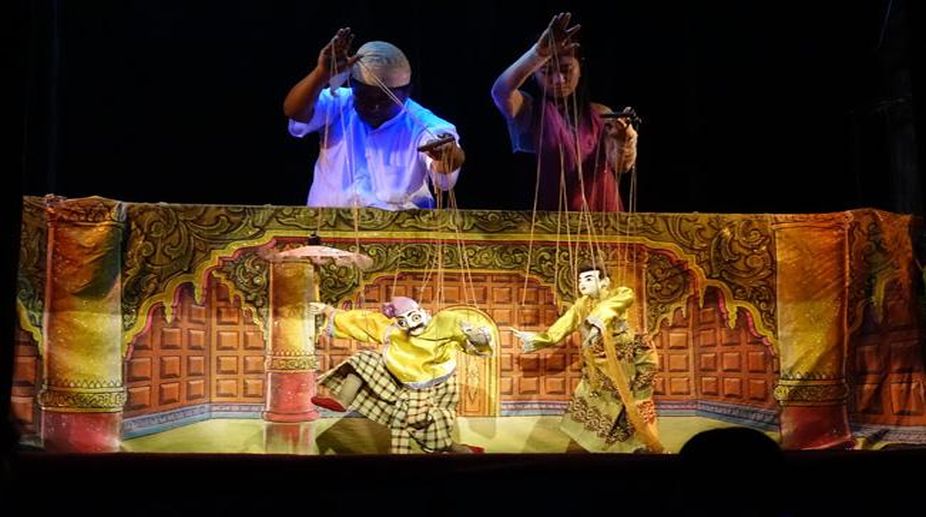

The first play, At the Sound of Marching Feet (Payer Awaj Pawa Jai) is from Bangladesh and written by Syed Shamsul Haq. The same text is translated into English by the author himself. The other entry from Bangladesh is called Life of Araj (Araj Charitamrita), written by Masum Reza and translated by Bina Biswas and Sayantan Gupta. Of the two entries from India we have The Djinns of Eidgah by Abhisekh Majumdar and The Far-Reaching Night (Bahut Dur Tak Raat Hogi) by Zahida Zaidi and translated by Ameena Kazi Ansari. The two plays from Pakistan are We Shall Resist(Hum Rokaen Gae) by Anwer Jafri, translated into English by Sheema Kermani, and Watch the Show and Move On(Dekh Tamasha Chalta Ban) by Shahid Nadeem, translated by Shuby Abidi. All these six plays seem to be in conversation with one another in contexts of competing nationalist narratives predicated on Islam in South Asia. The playwrights may or may not be much aware of one another’s works, although their plays sometimes cross borders to take part in the region’s annual theatre festivals and seminars.

As the editor makes it clear, the book hopes to establish a connection between the plays, thus creating a complex framework of South Asian theatre around the narrative of Islam —a pattern that broadly hinges on the plays’ abiding as well as changing contours of relationship with society and politics. Islam, as a spiritual worldview, is, therefore, less the theme of any of the plays here, and more of a trope which, tempered within the crucible of divisive politics in colonial and postcolonial South Asia, has been used to breed and foster narratives of nation-making that continue to largely affect the state of affairs in the region. On the other hand, the targeting of Islam —or unequal treatment of its followers in places where they are the minority —becomes an equally significant aspect of this anthology. The concerns addressed in the plays in this book go beyond the clichéd frame of communalism to incorporate much wider patterns of life woven circuitously around the political and personal exploitation of a faith, as much by its professed followers as by its detractors.

This anthology further demonstrates how theatre, in its different forms, supplements conventional history, which cannot often help leaving out of its purview the intangibles of the past —such as feeling, belief, and memory —and thus betrays its own inadequacies and erasures. The plays invite comparison with one another, engaging with this situation from perspectives of the three countries concerned — the idea of azadi countering the performance of state-sponsored nationalism and the predicament of life in the Kashmir Valley today (The Djinns of Eidgah, 2012); Hindutva politics shaking the long-held principles of a plural India, and often threatening to erase the religious “Other” (The Far-Reaching Night, 2006); sectarian violence and abuse of Pakistan’s blasphemy laws by self-professed guardians of Islam (We Shall Resist, 2009); Islamisation of Pakistan at the expense of political governance, and persecution of non-Muslim minorities (Watch the Show and Move on, 1992); the clash between ethno-linguistic and religious nationalism, culminating in Bangladesh’s Liberation War (At the Sound of Marching Feet, 1976); and censorship of production/dissemination of scientific knowledge and threat to the lives of secular liberals in the country (Life of Araj, 2001).

As nation-building in South Asia remains a continuous, unfinished product, trouble keeps brewing around the contesting constructions of the “Muslim” subject by Muslims as well as non-Muslims of a geo-political and cultural space that they have co-inhabited historically. The plays also underscore the need to resist violence in the name of faith, and uphold the ideals of plurality and hospitality across the region. Widely performed but largely unpublished, these six plays with their geographic and stylistic range provide a good spectrum of some of the best writing in contemporary South Asian drama. The editor, who has in his lengthy introduction offered us a framework for studying the plays as both texts and performance pieces, needs to be congratulated for clearing the reader’s mind of a lopsided understanding of Islam related to be the source of all political malaise and other forms of religious fundamentalism.

The reviewer is professor of English at Visva-Bharati University.