The way secularism was understood by the preIndependence Congress party, and the rejection by Mohammed Ali Jinnah and leaders of the Muslim League of this construct, led to the partition of India. Its enshrinement in the Constitution, through provisions that sought to ensure the state’s neutrality in religious affairs, and later by the addition of the word ‘secular’ in the Preamble, legally endorsed the idea, even though it was antithetical to votaries of Hindu majoritarianism, principally groupings that are the ideological predecessors of the present ruling dispensation.

But secularism in India has never meant separation of the state from religion; on the contrary, differentiated treatment in the personal sphere confirms the state is empowered to both legislate and administer religious affairs; indeed as some scholars have pointed out the Constitution allows extensive State interference in religion. Secularism in the Indian context thus embodies religious tolerance, quite distinct from Western liberal notions of separating church from state.

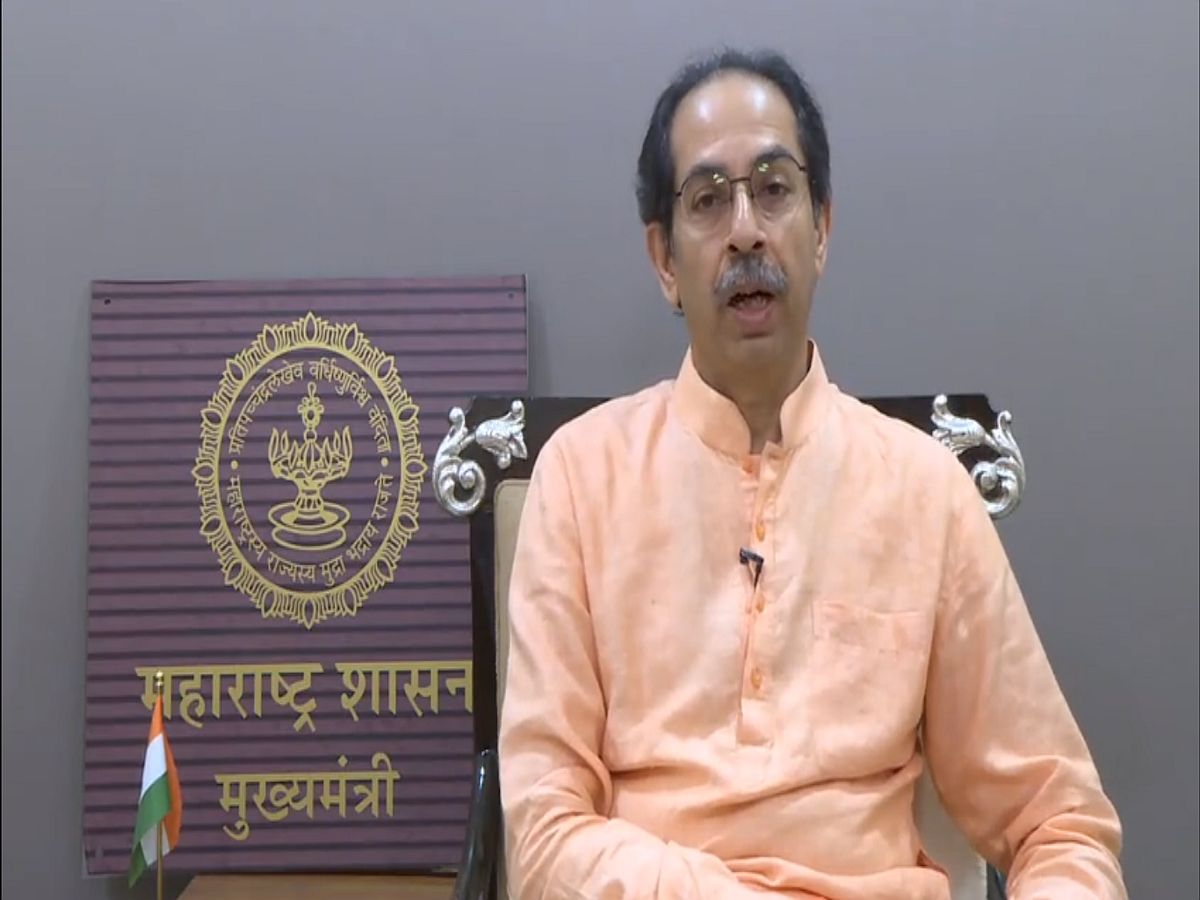

Be that as it may, the fact that secularism forms a part of the Preamble, and thus seeks to define the Constitutional discourse, means that it must be deemed a virtue, indeed a cornerstone of governance. Maharashtra Governor Bhagat Singh Koshyari’s somewhat derisive question to chief minister Uddhav Thackeray ~ Have you suddenly turned secular? ~ must be viewed in this context. For it seems to imply several things.

First, it would seem to suggest that not immediately conceding a demand to open temples is a decision born from a misplaced sense of secularism. The temples remain shut because of fears that their re-opening might see a surge of afflictions in a state that has seen most cases of coronavirus. Opening places of worship is a matter within the administrative competence of the state government, and while the Governor may raise his concerns, he is out of line when he links it to notions of secularism.

Secondly, the question might reasonably be construed to mean that in Mr Koshiyari’s assessment, the Chief Minister was not secular in the past and has only become so now. The Governor and the Chief Minister are both bound by their Constitutional oaths, and that by itself means they must pay obeisance to secularism, without allowing subjective interpretation or ideological persuasion to come in the way.

It may well be that Mr Thackeray was un-secular, or even rabidly communal, before he took oath, but once he did so he had no option but to be secular. This applies in even greater measure to Mr Koshyari for unlike the Chief Minister who must bear true faith and allegiance to the Constitution, the Governor must swear to preserve, protect and defend the Constitution. As the man who made Ministers of the present government re-take their oath for deviating from the script, Mr. Koshyari cannot be unaware of his Constitutional obligations.

And if he is imagines that the Constitutional ideal of secularism can be reduced to a jibe, he has no business occupying Mumbai’s Raj Bhavan. This is a slippery slope, and the President must rein in his Governor.