Farooq Abdullah says will meet same fate as Gaza if Indo-Pak talks don’t resume

Abdullah said that the matters should be resolved through dialogue.

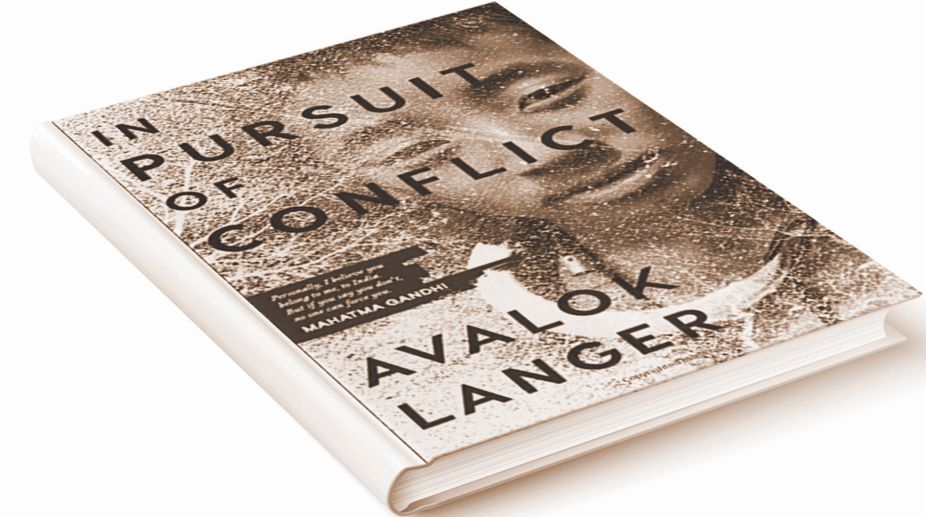

The story of insurgencies is told through riveting testimonies of underground leaders, with rare insights into the psychology, history and economy of this conflict zone… A review

In Pursuit of Conflict By Avalok Langer.

Although all Indian borders to the north are volatile, the older generation has mostly heard about the Khalistan problem in the 1980s and the Kashmir issue in this century. Anybody following the mainstream media is vaguely aware of armed insurgency in the North-east, but not the whys and wherefores of these conflicts.

Fortunately, young journalist Avalok Langer had the passion and the guts to pursue insurgent leaders in the region as a “conflict journalist”, the modern-day equivalent of a “war correspondent” at a time when undeclared wars and guerrilla warfare are the order of the day.

He has come up with a winner of a book, a tome that opens your eyes to facts that are sometimes outrageous and sometimes a comment on misguided human aspirations.

Advertisement

Langer establishes his street credibility by allowing the reader to get intimate glimpses of his love life (a failed relationship with a girl called Azo) as also describing vividly the discomforts and uncertainties of his efforts to meet leaders behind the conflict.

This is exclusive material because media reports that finally make it to print shave off all these details with ruthless professionalism, in the interests of carrying a crisp presentation that competes for attention with other headlines on the page. Here, the author has the luxury of describing landscapes, people and situations with all the flourish of someone who loves his subject.

The book will be read with more interest now that the BJP has firmly established a foothold in the region, because the people themselves are ready to vote for a national party rather than stick to tribal and other primordial loyalties. It is also a sign of fatigue after decades of fighting for a cause that doesn’t seem any nearer to realisation — a separate identity, self-governance and sometimes, a separate nation.

There are intimations of this weariness in the book. Sample this, “We had spent the better part of the afternoon with Julius and he was now looking tired. After all, fugitives do end up like this… after years of dodging, hiding and manoeuvring, it is their physical health which is most impacted.”

At the time the author interviewed him, Julius had come overground, much to the dismay of his organisation, the HNLC, and was on heavy medication. He even admits to the author, “Enough of this outsider blame, the problem has to be fixed from within.”

On the same lines, the author is told by BK Hrangkhawl, whose TUJs was launched to fight for rights to land, “We may have picked up arms to fight for the people, but with time an armed struggle starts working against the people. There are always selfish individuals who are focused on fulfilling their own monetary and sexual desires.”

He spent years in jail and later became an elected representative, provoking his group to feel the cause had been betrayed, and splinter like dry tinder. Another former-militant says after giving up the gun, “Immigration is a problem between India and Bangladesh, so why should the tribals of Tripura fight it alone?” Slowly, the futility of the fight against a bigger entity had begun to dawn.

It is easy for readers sitting outside conflict zones to wonder why militant leaders fight so hard that their entire society’s psyche is shattered. Did we have it easy and are the border areas suffering from a collective schizophrenia, that they don’t mind sacrificing their own lives rather than be ruled from Delhi? Wasn’t there enough bloodshed at Partition to expect everybody to shy away from that elusive goal of sovereignty?

Certainly, migration of young people for jobs must have brought the realisation that there is nothing terrible about living in the Indian Union, despite racist attitudes that sometimes spark violence. Meanwhile, the whole of the North-east is at the hands of gun culture, with both the government forces and rebels being armed to the teeth and ready to pull the trigger.

An interesting thread in the book is the search for the money trail, as without funds the rebels would not have been so well armed. The number of SUVs lining the road to simple village huts is startling. An ageing Naga leader wears a Tag Heuer watch. Shockingly, the author finds, gangs collect taxes within sight of army camps and police posts. Everybody seems to benefit from the fact that it is a conflict zone, except humble people.

“At the time, the government had allocated an annual budget of 1,750 crores to Nagaland, of which different underground groups were grabbing an estimated 600 crores every year. This money was and is even today being used to buy arms, maintain camps, pay cadres and run a parallel government, all with the complete knowledge of the state government,” he explains. So we know now where development funds go.

Then there is the drug circuit. Consignments are transported even through peaceful states like Manipur to fund the rebels, making 76 per cent of its population intravenous drug users. Proximity to the “golden triangle” of Myanmar, Laos and Thailand has proven to be deadly.

Langer is told of army involvement but shies away from exploring it further, as he is himself an army kid. Later, he hears news of the arrest of some rogue army elements for handling consignments.

There is an isolated tribal group that grows so much opium it is second only to Afghanistan. It’s deplorable that militants fighting for their people don’t mind the fallout in terms of widespread drug abuse in the area. Can the end ever justify such means?

A good bit of colonial history is part of the narrative, interspersed with personal experiences and interviews, which makes it easily digestible. For instance, while consolidating their hold over the Garo Hills, which later came to be a part of Meghalaya state, the British brought along Bengali administrators, Nepalese soldiers, Marwari traders and the church.

Later, the presence of these outsiders gave rise to a feeling of disenfranchisement among local people. There seems to have been a devilish game to turn this disgruntlement into a source of anger towards “India”.

It is not as if the rest of India, say Mumbai, did not experience angst of locals against outsiders. The difference seems to be that on the North-eastern border, there were foreign powers willing to fund insurgency and destabilise the newly independent nation, even gobble up a portion of it.

Talking of foreign interference, former rebel Sangupo Chase reveals in a hair-raising account that in 1968, he was part of the second contingent of 300 Naga rebels that went to China for training. They also underwent Communist indoctrination and were told that 750 million Chinese were behind them.

A secret pact was signed to create a “liberated zone” on a strip on the Burmese side of the border and wait for Chinese assistance, which would be of the level provided to North Vietnam.

They managed to return but meanwhile their colleagues had signed a deal with the Indian government that led to their betrayal and imprisonment. In the end, Chase wonders if the Chinese would have treated them as just another province, like Tibet, or allowed them to remain independent.

In this age of globalisation, how does the young reader react to all this information about conflicts of tribals versus non-tribals, locals versus immigrants? After all, people from the mainland are willing to move to the West for better jobs, to escape conservative societies and fit into ecosystems where they are not only minorities but branded as black.

Others, living in cosmopolitan cities, have changed their eating habits and taken to western dress, but still retained their clan’s distinctive culture even when surrounded by the “other”.

Perhaps it’s time the North-east realises that the rest of India also experiences political alienation, financial anxieties and anger against corruption. It’s also time we reciprocate by visiting Manipur, Arunachal Pradesh and all the other states as tourism opens up, especially with this book in hand.

The reviewer is the author of In Search of Ram Rajya and That’s News to Me

Advertisement