PM spells out India’s position on China

I n a recent interview to Newsweek, the Prime Minister, discussing Indo-China relations, commented, “For India, the relationship with China is important and significant.

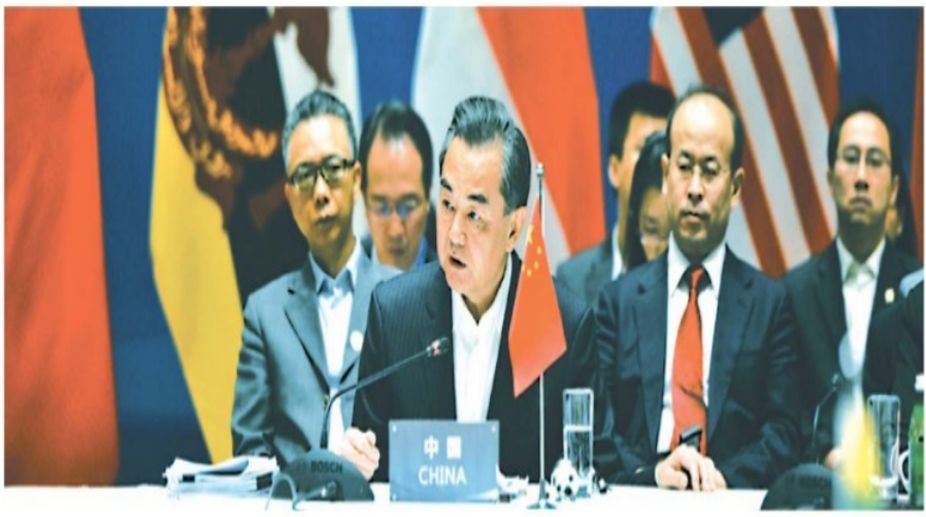

ASEAN (PHOTO: SNS)

China has deepened its influence on ASEAN nations, and the just-concluded ASEAN Summit with its chairman’s watered-down statement stands testimony to this.

This China factor — coming on the back of Beijing’s huge investments as well as more intense diplomatic activity in the region may continue to feature prominently in future ASEAN meetings — at least for this year.

China is currently the biggest trading partner of most of ASEAN members, and their biggest or a significant investor.

Advertisement

The outcome of the recent meeting of the 10 top leaders of ASEAN — Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, Brunei, Thailand, Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar, the Philippines and Vietnam — shows the majority wanted a non-confrontational approach towards the Middle Kingdom on the South China Sea issue.

Before the April 28-29 ASEAN Summit, there were expectations that most ASEAN heads of state would raise concerns over China’s conduct in the disputed waters of South China Sea.

China is claiming most of the energyrich South China Sea, through which about $5 trillion worth of trade passes every year. Brunei, Malaysia, the Philippines and Vietnam, as well as Taiwan, also have sovereign claims.

But in recent months, China has not only built reefs and structures in several parts of the disputed area, it has also installed military facilities there, according to reports citing satellite images.

Due to a growing Sino-Philippine rapprochement, few expected Rodrigo Duterte — the Philippines president who is the rotating chairman of ASEAN this year — to take a tough stance. However, it was unacceptable to many to see the removal of the term “serious concern” from the chairman’s final statement after the conclusion of the summit. These words reportedly had appeared in previous ASEAN pronouncements.

“China’s influence in ASEAN has increased, but this is expected. However, ASEAN chairing country does have an important role in shaping the outcome of summits and meetings,” says Ngeow Chow Bing, deputy director of Institute of China Studies, Universiti Malaya.

“If the chairman decides not to pursue a certain stand or posture, this will be reflected in the outcome. Given that under Duterte, a new, more conciliatory policy has taken shape in the Philippines, this outcome is something not too surprising for us,” he says.

Since becoming president last year, Duterte has reoriented Philippine’s foreign policy. He is working on rebuilding Sino-Filipino ties to bring in Chinese investments into his country, after a fiveyear hiatus.

He started his overtures by sidelining a landmark arbitration case that decided in favour of Manila. The July 2016 Hague ruling invalidated China’s claim of sovereignty over South China Sea. China refused to recognize the decision.

Following a visit to Beijing last October, Duterte saw positive results from his policy change.

Fruit exports to China resumed and Filipinos were allowed to fish in disputed waters. Beijing’s promised soft loans and multi-billion dollar investments are being discussed. Chinese tourists are returning in droves.

Duterte told reporters it was “pointless” for ASEAN to pressure China. In his opening address to the summit, he made no mention of South China Sea. Duterte’s overly pro-China moves have caused unease. Richard Javad Heydarian, political science professor at De La Salle University in the Philippines, writes in his opinion piece:

“During the ASEAN Summit in Manila, reports suggest that Duterte not only declined to raise the Philippines’ arbitration case, he also vetoed any reference to China’s massive reclamation activities which have given rise to a sprawling network of military facilities in the high seas.

“This resulted in a chairman’s statement taking a softer stand on South China Sea maritime issues. By any measure, this was a slam-dunk diplomatic victory for Beijing, which has sought to court Duterte by offering multibillion-dollar investments and the prospect of joint development deals in contested waters.”

He warns that ASEAN, which marks its 50th anniversary this year, “risks fading into irrelevance and risks undermining its internal cohesion and centrality as an engine of peaceful integration in the region”. China is satisfied with Manila. On May 2, it welcomed the chairman’s statement and reaffirmed cooperation with ASEAN on the South China Sea issue.

According to Ngeow’s observation, ASEAN members that had stood by Duterte were Laos and Cambodia — two of the world’s least-developed and poorest nations that have benefited tremendously from China’s investments.

From the very beginning, China has been helping socialist Laos — largely shunned by investors. China’s cumulative investments in almost all sectors totalled more than $5 billion. Currently, China is also building a $7 billion, 1,022-km China-Laos high-speed rail scheduled to complete in 2020.

Cambodia, which only attained peace in 1989 after being devastated by civil war and Vietnamese invasion, saw aid and investments coming from China since 1994. With total investments of over $10 billion within 1994-2012, Chinese firms are now in control of Cambodia’s power supply.

It is no wonder that in 2012, while serving as rotating chair of ASEAN, Cambodia stopped ASEAN foreign ministers from issuing a joint communique that contained wordings on the disputed South China Sea. Echoing the stance of China, Cambodia said these disputes were “bilateral” rather than multilateral. Traditionally, Thailand and Myanmar have been neutral on the South China Sea issue as they are not claimants, says Ngeow. Hence, it was likely they did not push for the issue at the Manila Summit.

Currently, China is Thailand’s largest trading partner and second largest foreign investor. It has named Thailand as a recipient country under the Belt and Road initiative of President Xi Jinping due to its location and close ties with China.

According to a Reuters report, four ASEAN member states had disagreed with omitting “land reclamation and militarization” from the chairman’s statement.

The three nations that held strong views for a joint stand on the maritime waters were Singapore, Indonesia and Vietnam. Malaysia — which had in the past taken a very conciliatory stance on South China Sea issue — was lumped together with the three nations by news reports. Hence, in terms of number these four countries were in the minority at the summit.

According to Heydarian, Duterte’s decision to block any robust ASEAN statement on South China Sea disputes was likely due to the deals Manila might sign with Beijing. He is scheduled to meet Xi on the sidelines of the May 14-15 BeltRoad conference.

“Duterte will likely seek not only major trade and investment deals, but also explore a modus vivendi which will allow the Philippines to have easier access to contested waters and resources in the South China Sea,” says Heydarian.

In addition, the ASEAN Summit was tame on China partly because nations have witnessed the impact of China’s action or inaction. Due to its pro-U.S. policy, South Korea’s tourism and retail investments have been hit recently.

Many ASEAN nations are eager to seek economic benefit from China. “Continued world economic doldrums means China investments are increasingly important for many ASEAN members,” says Oh Ei Sun, senior fellow at S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies at Nanyang Technological University.

But economic deals and economic ties might not be the sole influencing factor. “Many nations think about the longterm consequence of a China-confrontational policy. And also, can the United States always be counted on? Compared to the U.S., China is a geopolitical fact, a permanent presence in the region,” says Ngeow.

The Star/ANN

Advertisement