Bhutan now more accessible than ever

Bhutan, renowned for its majestic landscapes and unique cultural experiences, is now more accessible than ever for travellers, thanks to several key improvements in travel procedures.

Travel writing continues to serve as the primary genre for bringing home wider worlds, and it will do so as long as there are places to be discovered and rediscovered, described and imagined.

Bruce Chatwin

The first condition of right thought is right sensation — the first condition of understanding a foreign country is to smell it.

TS Eliot

For every trip that we make next time, be it near or far, within the country or abroad, single or family package tour, beaten track or a relatively virgin destination, it will be advisable on our part to write something about it, for this travel account may very well find a place in the travel column of the weekend supplement of a daily newspaper, or in a page of a family magazine, given the massive craze for travel today.

To exclude travel-oriented articles and pictures from its pages will be a risk for any daily or any periodical worth its salt as that will leave a sizeable portion of its readership disgruntled, thereby giving opportunity to rival publications to fill up the gap.

Advertisement

Although a penchant for travel has been a basic part of the human psyche, and innumerable travel accounts have been written by people for centuries, travel writing has grown tremendously in popularity only in the present age. All the major travel agencies — local, national or global — are offering all sorts of tempting paraphernalia in this regard, and their catchy advertisements in the print and the electronic media are really breath-taking.

“I shall drink life to the lees”, said Ulysses in Tennyson’s poem, and this lotus-eater spirit runs through the veins of all humans. Man’s increasing desire to explore new areas and visit places of historical or scenic beauty has got a new boost through the phenomenon called travel writing. “Travel is writing”, wrote Michael Butor, commenting on the recent rise of the professional travel writer, and capturing the close relationship that has always existed between journeys and texts.

Travellers make their way through space as the pen makes its way across the page. Depending on the charts and guide books written by earlier travellers, they produce, in turn, a wide range of documents — from single-line marking routes on maps to multi-volume narratives, complete with lavish illustrations and extended discussions of landscapes, languages and cultures.

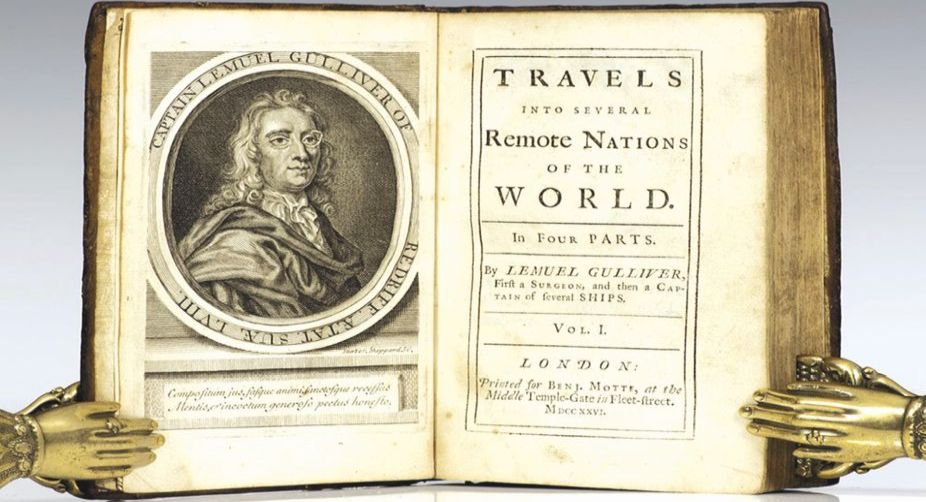

A number of literary genres have emerged from travels — most directly mock-travelogues such as Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels (1726), but also epic poetry, chivalric romance, picaresque narrative and science fiction. Although Swift’s book is an implacable satire on the human race (especially in Book IV), we also find an almost fairy tale description of Gulliver’s travels to such imaginary exotic lands as of Lilliputs, Brobdingnags, Laputas and Hounyhnms.

All great epics present great travel accounts, and Homer’s epic hero Odysseus, king of Ithaca, has become synonymous with the universal traveller. His very name means “trouble” in Greek, referring to both the giving and receiving of trouble — as is often the case in his wanderings. An early example of that is the boar hunt that gave Odysseus the scar by which Eurycleia recognises him; Odysseus is injured by the boar and responds by killing it.

The genre that came after the epic was the chivalric romance that first developed in 12th century France and this form of literature also dealt extensively with the travel experience of a knight who undertook a quest in order to gain a lady’s favour. One of the most famous chivalric romances that was composed in the 14th century is Sir Gawain and the Green Knight where we get wonderful descriptions of exotic places apart from those of chivalric ideals of that age. Picaresque narratives like Jonathan Wild also offer glimpses into locales that are similar to some of the basic features of travel writing.

Science fiction of Jules Verne (Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea, Around the World in Eighty Days, Journey to the Centre of the Earth), or HG Wells (The Time Machine, The War of the Worlds) read like travel literature and as the locale is set in another planet, we are given a wonderful portrait of those mysterious places that give the reader experiences of an extra-terrestrial trip.

Lots of structures and themes of classic short stores have been provided by travels — the hunt, quest, race, escape, shipwreck, mutiny, colony, reunion, and homecoming. There are also brilliant presentations of evocative landscapes in which the story unfolds — the island, lagoon, jungle, ocean, volcano, highway and mountain. By the end of the 17th century, travel literature had matured into a flexible and powerful literary form, providing information and satisfying the imaginative needs of readers who were increasingly interested in the wider world.

But it was only toward the end of the 20th century that English travel writing established itself as a prestigious authorial career. Bruce Chatwin, Paul Theroux, Colin Thubron and Jon Morris are among the biggest names in the business, and many other amateur hands venting their creative urge as soon as they have made a trip anywhere.

The sublime peaks of the Himalayas, the turbulent beauty of the seas, the dark green glory of the Dooars or of the Periyar forest, the snow-capped peaks of Switzerland, the Great Wall of China or the Leaning Tower of Pisa can easily ignite the poetic fire in the heart of any tourist who never before thought of taking up the pen to vent his soul’s voyage.

In the early phase of travel writing in English, we find two types of travellers — merchants and pilgrims, and they were closely associated with the textual travels of the 13th century Italian merchant Marco Polo and 14th century fictional pilgrim Sir John Mandeville.

Chaucer’s moral and religious allegory The Pilgrim’s Progress is an episodic travel tale which, while actually describing the soul’s voyage, narrates experiences of different fictional personages in different places and throws humorous light on peculiar customs and habits of different people.

But on many occasions description of fictional travels was not always inspired by actual visits to those destinations, which are portrayed in all their flavour in literary works. But with the passage of time the description of imaginary lands gave way to that of real lands visited by those who have later taken up the pen to record their experiences. Quite often actual visits to exotic lands were inspired by commercial interest. The rise of the British political interest in West Asia sparked a revival of religious tourism and by 1869, Thomas Cook was even offering package pilgrimages of Jerusalem for the British and American middle classes.

The surge of critical interest in travel writing in the 1990s coincided with the 500th anniversary of Columbus’ epoch-making landfall in the Caribbean. The English travellers must be grateful to Richard Hakluyt for the efforts he took to publicise their travel accounts. But Hakluyt’s first collection of travel narratives, Diverse Voyages Concerning the Discovery of America (1582), consisted almost entirely of non-English sources. Yet his great anthology of The Principal Navigations, Voyages, Traffics and Discoveries of the English Nation (1589) was pointedly assembled to celebrate the achievements of his own countrymen and to attract his government’s support for their new initiatives.

Although the merchant and the pilgrim started the vogue of travel writing, they were greatly superseded by the explorer, settler, scientist, and tourist. But, as has been mentioned before, the inspiration behind travel writing need not always be a trip to any religious site or place of historical significance.

Thomas More’s Utopia is concerned with the description of a fictional land named in the book’s title (the Greek — word means “no place”), providing ample opportunity for the writer to comment indirectly on the social and economic problems of England.

A journey to an earthly landscape often ends up in a journey to the interior of a traveller’s own psyche — a process dramatised with particular power in the travel fiction of Joseph Conrad. In his masterpieces like Nostromo, Heart of Darkness and The Nigger of Narcissus, the dark places of the world reveal the sickening sense of evil that lurks in the interior of the human soul.

Travel is also an occasion for the examination of the traveller’s own cultural baggage, resulting in the criticism as often as in celebration, and breaking down as much as reinforcement of identities. There are may factors responsible for the massive surge in travel writing — new technologies for travel and communication, the erosion of traditional class and gender barriers, and the intensification of interest (both financial and humanitarian) in the developing world. And as the first flights into outer space are being offered to wealthy tourists, it is only a matter of time, before extra-terrestrial travel accounts begin in earnest.

Travel writing continues to serve as the primary genre for bringing home wider worlds, and it will do so as long as there are places to be discovered and rediscovered, described and imagined.

Advertisement